Lost in Space: Season 2 Case Study

Case Study

In Lost In Space season two, the Robinsons continue their fight for deliverance to Alpha Centauri. The path is beset with danger, with malicious forces of the human, mechanical, and predatory variety all intent on keeping the family from their goal. Image Engine was called upon to leverage its 25 years of visual effects expertise, creating antagonist robots and alien fauna that would meet – and surpass – the thrill of those witnessed in season one.

Netflix is no stranger to reboots. Fuller House, One Day at a Time, and Mystery Science Theatre 3000: The Return have all found new life on the platform. Yet few reboots boast the Hollywood-level ambition, action, and cutting edge visual effects of Netflix’s epic Lost In Space revival.

Lost In Space debuted in 2018, launching onto televisions around the world with operatic scope, alien worlds, and imaginative CG characters that set a new standard for streamed sci-fi. Now, the second season has landed, and it ups the ante across every facet of the show’s drama. Image Engine, who supplied 266 shots for season one of the Robinson family’s adventures, returned once again to support those aspirations, ensuring that the ongoing saga of Maureen, John, Will, Judy, and Penny felt more gripping than ever.

Read on to learn how the studio leveraged its 25 years of expertise across digital creatures, environments, FX and more to create both robotic and organic adversaries that would meet – and surpass – the thrill of those witnessed in season one.

Danger, Will Robinson

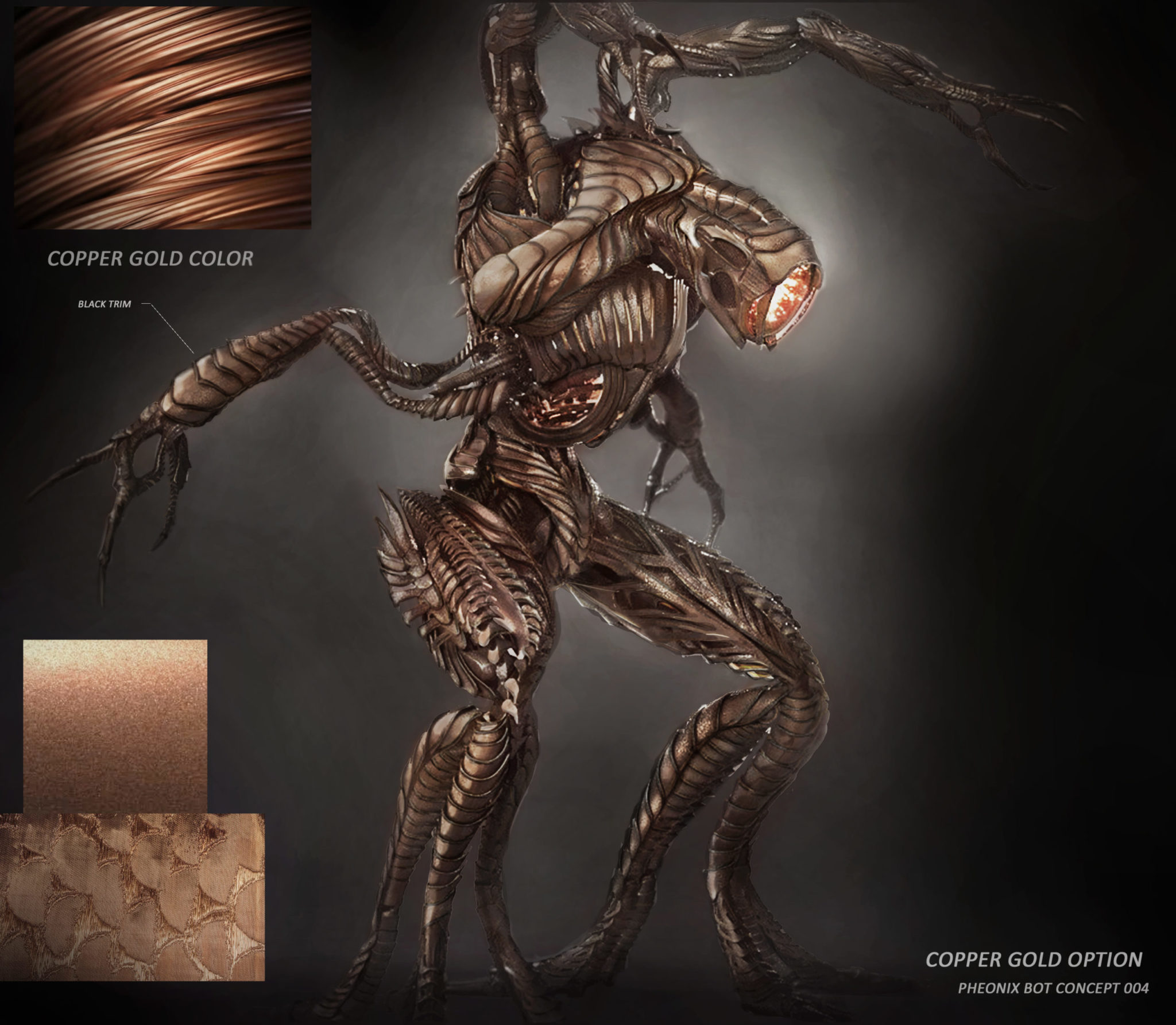

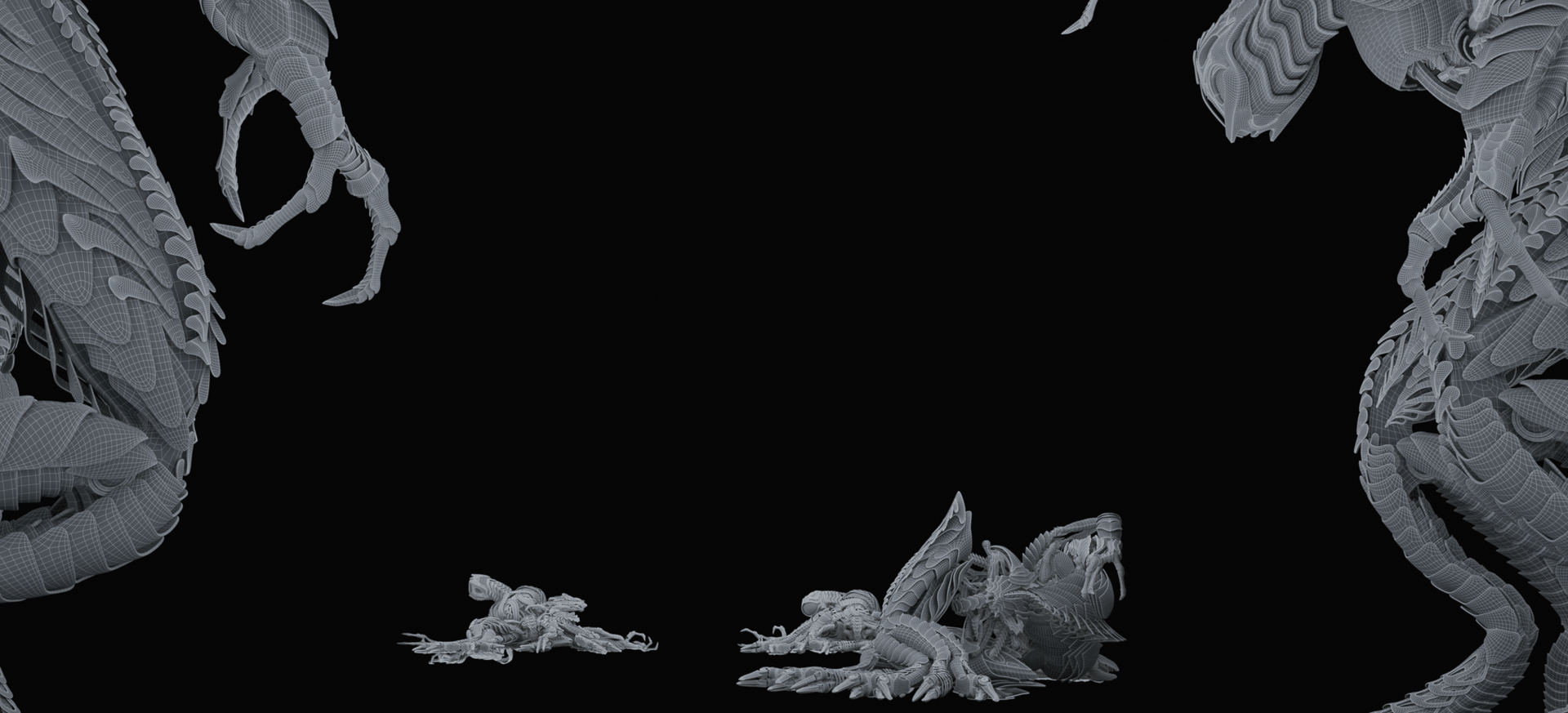

For Lost In Space season one, Image Engine created two robots: the Robinson family’s protective paladin and SAR, his malicious mirror image. This time, the team turned once again to SAR, alongside Thar and Phoenix, two new robots that both played a central role in the season’s twisting narrative.

“We subtly progressed the designs of the robots, without moving too far from the original series’ design, given only seven months had passed in the show’s narrative,” begins Andrew Walker, VFX Supervisor on Lost In Space season two. “The design brief for Thar, the robot commander, was that he should like an iPhone 10 compared to an iPhone 8. Shinier, bigger, badder. With the evil robot specifically, he had to communicate more of a commander-like aspect, given that this season sees him leading a robot horde.”

The scene to which Andrew refers takes place in episode 10 – the second season’s epic finale. In the episode, the interstellar spacecraft named the Resolute becomes the front for an epic battle against a legion of marauding robots. The sequence of events that details their infiltration and attack required a considerable and diverse contribution of work from Image Engine. These contributions included the robots’ ship docking with the Resolute, its insect-like invaders navigating the spacecraft’s corridors, a confrontation with Will Robinson, and, finally, the intense robot-on-robot conflict.

The latter sequence is the series’ defining action moment, portraying a one-against-many corridor fight as Scarecrow blasts and wrestles his way through twisting metal, searing fire and shattered glass. The sequence is as exhilarating to watch as it was complex to create.

Robot Wars

“The main fight sequence was greenlit just a few months before delivery – but that didn’t stop us from preparing everything we needed for the sequence up until that point,” says Andrew. His team commenced by creating a rough edit of what was possible in a corridor confrontation based on content from other movies, then prevized the sequence, blocking out the moves the robots could perform, setting a pace and rhythm, and establishing camera moves.

When it came to tackling the sequence for real, the team was fully prepared to build out a meticulously choreographed eruption of violence. The animation team still had its work cut out, as artists contemplated the four flailing limbs of each robot, the tearing apart of mechanical chassis, and numerous brutal interactions with the surrounding environment. And then they had to fit a camera among all of it. “The camera was really dynamic,” says Jenn Taylor, Animation Supervisor. “It was orbiting and circling the robot action, an idea which came from some of the kung fu films we referenced earlier on. We also animated it as if a cameraman were holding the camera and walking in and around the ensuring action. It became a character in and of itself.”

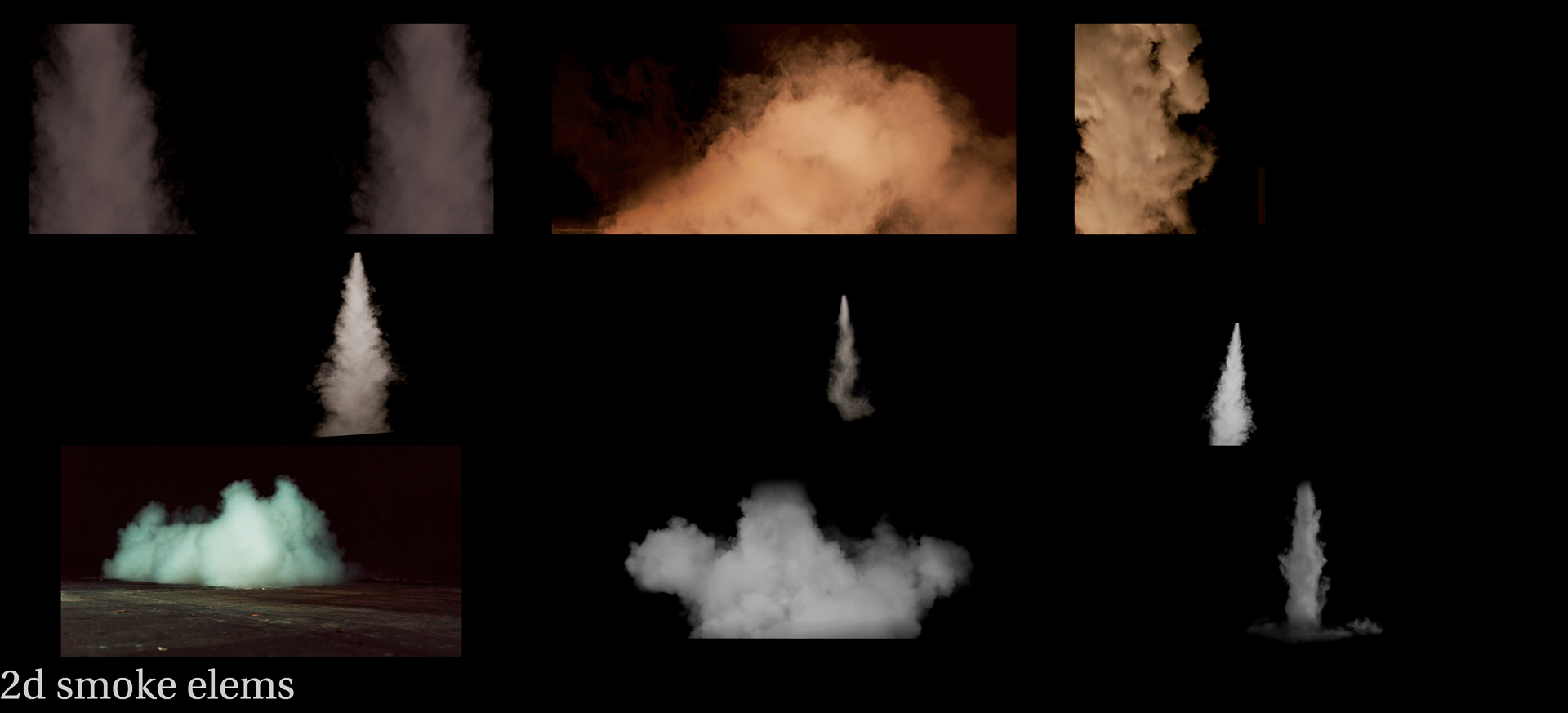

The FX team also contended with a significant amount of work. When robots fight, there’s destruction, and where there’s destruction, there’s FX. Image Engine created multiple layers of spark, smoke, and other volumetric effects, all of which the studio handled entirely within SideFX’s Houdini platform.

“There was so much going on in that scene,” says Michael Billette, Lead FX TD. “In season one, we’d do two or three blasters in a whole sequence. Here we were doing that in half a shot. The sequence also sees a fire ignite from a broken pipe, which in turn sets off a CO2 fire suppression system, all of which required a very high-quality volumetric system that could interact with the characters and hold-up to scrutiny for close-ups.

“We also had to think about the ship porthole breaking, when Scarecrow plows into it,” he continues. “That was four layers of broken glass we needed to simulate, not to mention it all getting vacuumed out into space along with the smoke, fire, debris, and robots. The scene just kept upping the ante in that way, with more volume layers and more complex interactions to consider. It was an exciting challenge to think about!”

The work is all the more impressive when you consider that not only did Image Engine artists simulate the above – they lit it, too. “It was a complex render because most of the lighting was bounce light,” continues Michael. “When you consider the number of light sources – the flashing emergency lights, the lights from the blasters, the lights from the ships outside – things got super crazy. We had to do a lot of technical thinking to optimise the scene and choreograph the lights to the action beats. It was a hugely complicated setup, but thanks to that hard work, it felt completely seamless and conjured a great mood and atmosphere throughout the sequence.”

Creating a corridor

The corridor environment in which the battle transpires also required a thoroughly attentive approach. Given the dynamic nature of the cameras and the alterations required by Lost In Space‘s producers throughout the sequence’s creation, the Image Engine assets team built a full CG set. Using this asset, artists could react to changes as needed with an environment that met the narrative requirements of the episode.

Case in point: the production’s desire that the final battle sequence didn’t focus solely on the robots but, importantly, also reminded viewers of the Robinsons and their plight. That meant adding windows to the corridor that revealed the Jupiter 2’s fraught escape outside the Resolute.

“We ingested the exterior of the Resolute from another vendor and performed some extra detail work on it, as our shots were closer to the hull and would undergo extra scrutiny,” says Barry Poon, Assets Supervisor. “It also meant that we needed to integrate our interior hallway with the exterior of the ship. That way, the camera could capture a shot looking from the outside in. However, as the curvature of our CG asset hallway was different from that of the exterior of the ship asset, we needed to redesign a section of the exterior ship to fit the frequency of our interior corridor details. We then created a refactored interior corridor, which worked with the curvature of the exterior. Thanks to great effects like this, audiences ultimately enjoyed a seamless sequence. It works not only technically but narratively, in that it neatly juxtaposes the robots’ interior struggle with the humans’ exterior escape.”

The assets team also leveraged a new variation set up in Image Engine’s Jabuka asset manager to ensure any changes made to the corridor didn’t impact on the flow of the narrative.

“As we were integrating with both plate and full-CG footage, a huge number of variations were required of the corridor asset as the sequence progressed. More so, in fact, than any other asset ever worked on at Image Engine,” says Barry. “That introduced logistical challenges, such as ensuring artists used the correct version of the corridor at the right moments in the battle.

“Thankfully, using our new Jabuka feature, the animation team could switch the state of the corridor in a more automated way, by setting the sequence on a shot-by-shot basis depending on what variation they would be using. That offered more control while also making the corridor assets keyable during the shot. The artists could dent a wall if a robot were thrown into it, for example, and work in confidence that the Jabuka system would automatically drive the model switch as well as the texture and look dev switch. That ensured physical consistency across shots, which in turn maintained the rhythm and immersion viewers felt when watching the battle.”

An intrusion of cockroaches

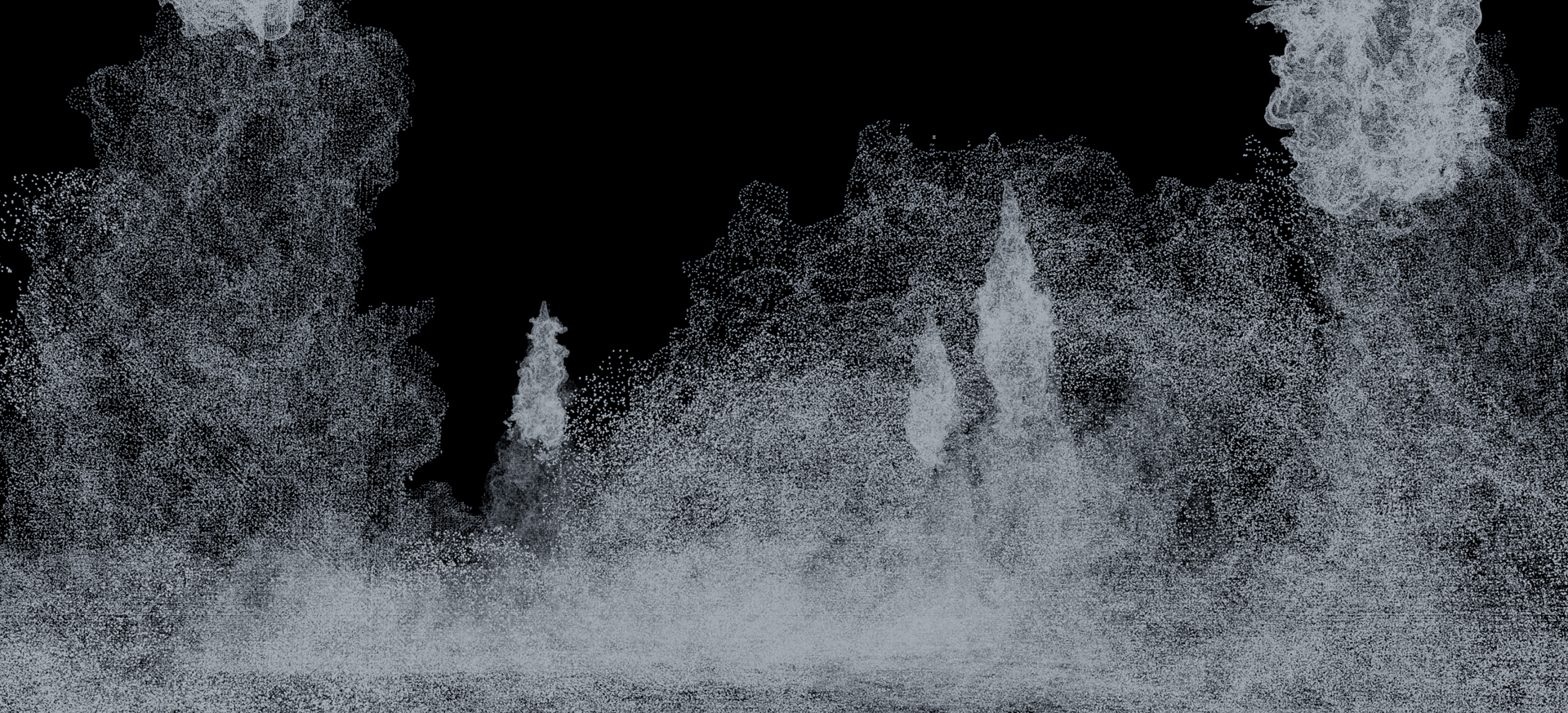

The lead up to the main confrontation starts when the evil robots first blast their way into the Resolute from a ship attached to its hull. An explosion detonates in the ceiling, through which the robot horde swarms like an intrusion of cockroaches.

“The robots spill out over the walls and bulkheads, crawling up and around as they move through the ship,” says Jenn. “We had to make sure that felt believable, which meant optimising our animation rig from season one for the hero robot, while also creating faster and lighter versions for the crowd-driven characters.”

Image Engine adopted the third-party Atoms Crowd tech into its Maya pipeline to manage some of this crowd animation. “The walls aren’t flat – they have beams and poles and various outcroppings the robots had to navigate. Atoms Crowd massively helped with that,” says Jenn.

More subtle, hand-keyed animation was also required just before the main confrontation. When Will confronts the attacking robots, they show signs of doubt, a reaction related to their connection with the character, and a significant narrative moment. “Communicating that significance is a challenge, given that the robots have no faces to emote,” says Jenn. “However, we’re more than used to that at Image Engine. We displayed the robots’ confusion by having them break military positioning and adopt a more questioning attitude. It’s a subtle reaction, but one that illuminates the importance of this moment to both Will as a character and the episode itself.”

Image Engine’s animators contributed to another notable story beat in episode six. Here, audiences witness SAR’s masquerade as the Robinson’s friendly robot come to an end. His transformation from the bipedal, humanoid-looking robot into the insidious insectoid with four arms is a big plot twist – and one that needed to shock the audience at home.

“The production wanted the transformation to feel organic, like a beetle whose plates were shifting into a new formation. You can see the exoskeleton realign as the robot’s posture changes, and the head moves into a more threatening stance,” says Jenn. “We achieved this animation using a series of rigged controls, allowing the animator to hand key each individual plate as they fanned out. The result is a super cool animation that tells the viewer in an instant just who this character is and what their motivations are.”

Following the transformation, SAR turns to kill his exposers Maureen and Will, but the mother and son are saved by Adler, who enters the scene brandishing a glowing EMP device. Using it causes SAR to crumple and contort inwards as sparks, plasma and bolts of electricity arc from his disintegrating carapace. “The brief was to make it a big event to cap off the sequence, so we really went to town!” says Andrew. “It was a cross-departmental exercise and the shot was passed between animation, modelling, and FX quite a lot. The results are fantastic, and end the episode with a truly satisfying victory for the Robinsons.”

Vivacious creatures

Image Engine directed its focus not only towards the metal platings and serrated claws of killer robots but also towards the creation of the flesh-and-bone creatures dubbed “Vivs”. Episode five sees Judy Robinson and her father struggling for survival on an alien planet of ochre rock. Here, Judy must sprint from one checkpoint to another while pursued by the planet’s indigenous – and none-too-friendly – lifeforms.

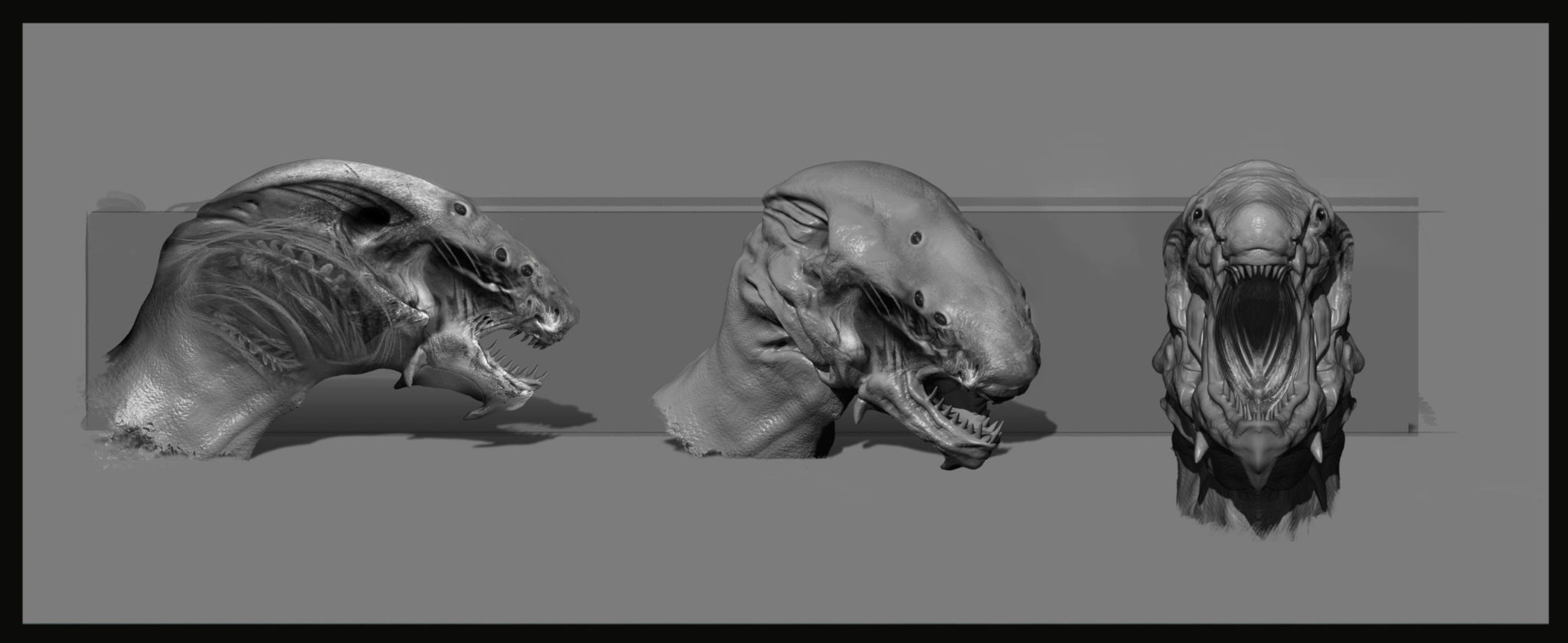

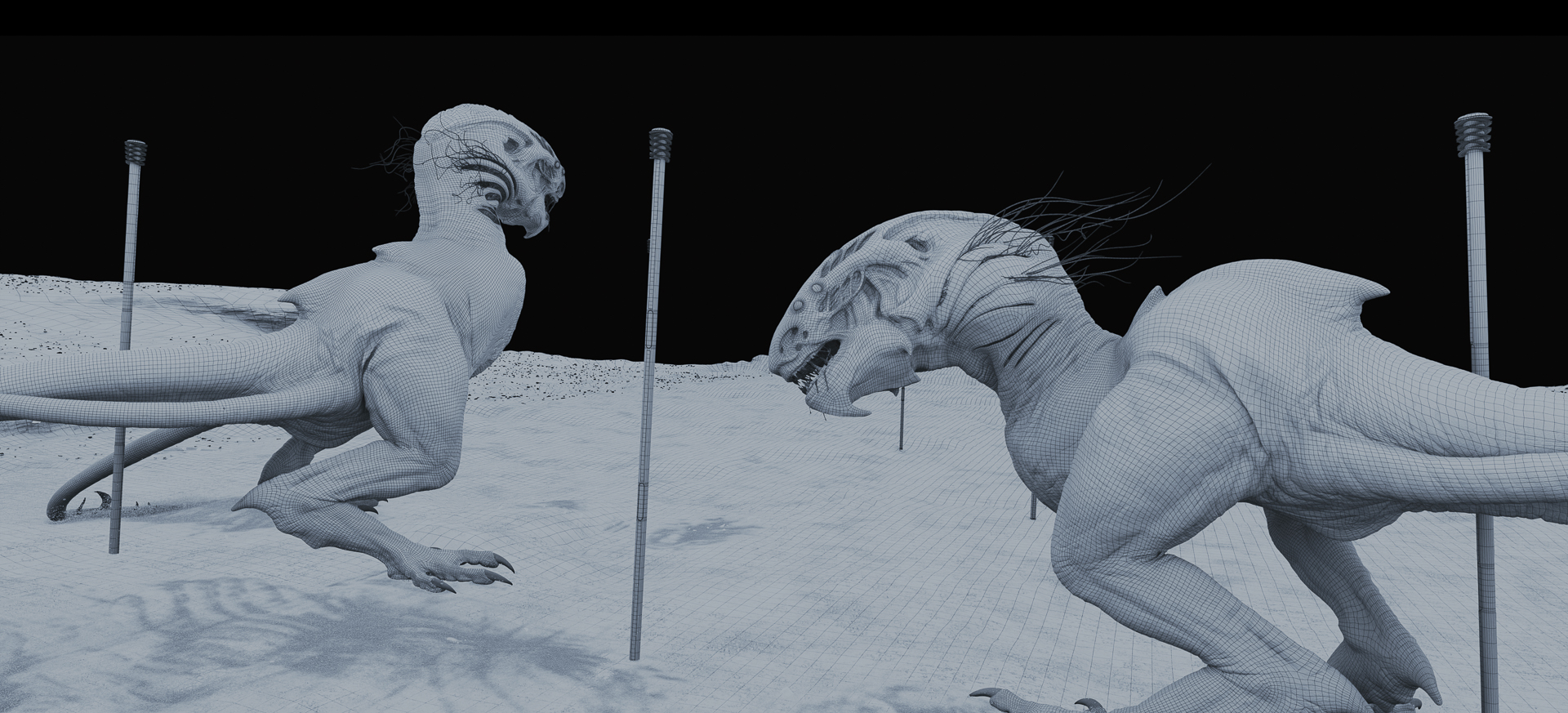

The Vivs are velociraptor-like carnivores with three tails, broad, teeth-encrusted skulls, and a penchant for parkour. Image Engine was entirely responsible for the design of these creatures and carried out a concepting process throughout which the Vivs adopted a broad spectrum of forms. These included a spidery incarnation and several grotesque, horror-film aberrations before the final design, as seen on screen, made the cut.

“Our work on Jurassic World undeniably helped with these creatures,” says Andrew. “From day one the animation and look dev looked great, because the team knew exactly how to create that kind of creature, right out of the box,” says Barry.

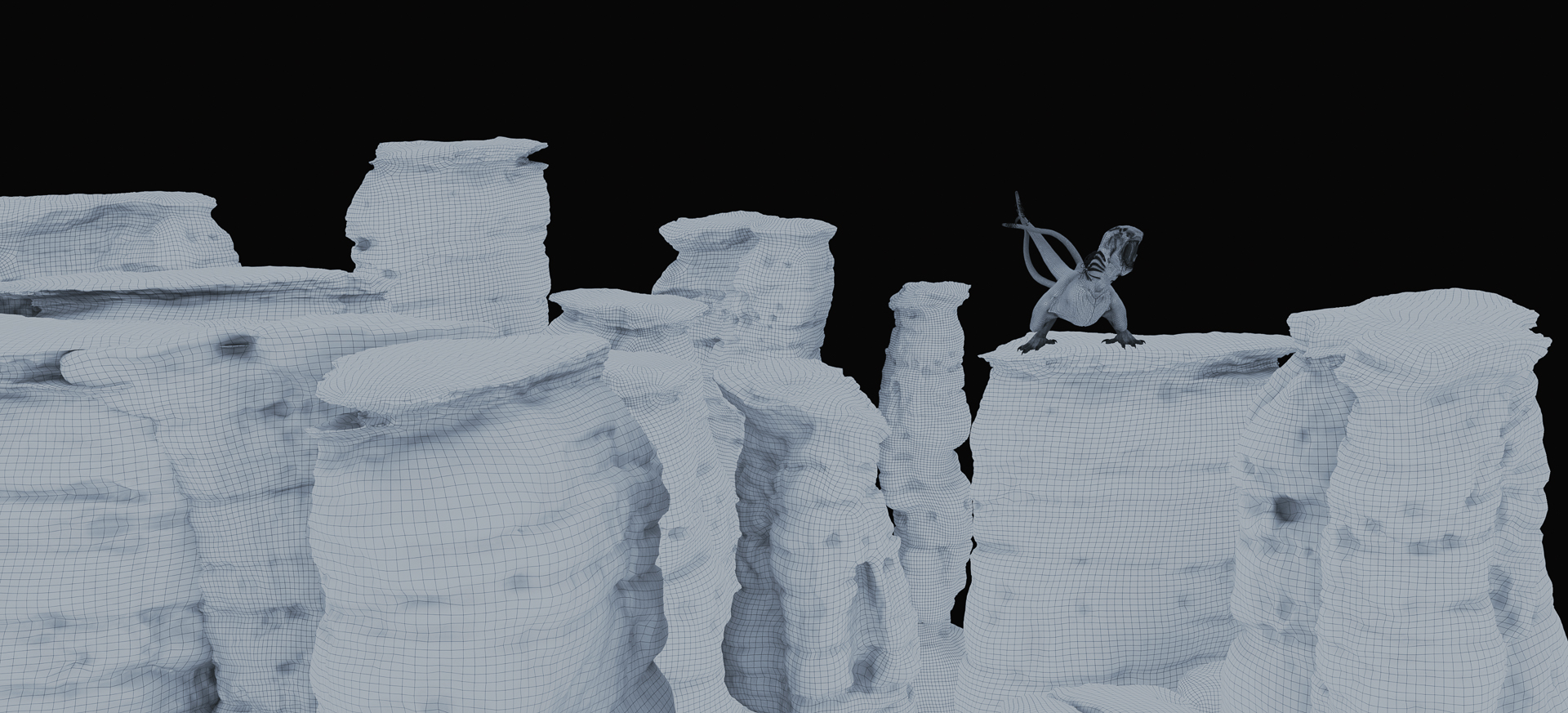

The team’s biggest challenge was finding a way to have these creatures navigate the rocky environment in which they appear without breaking the tension of the sequence. “We needed to make these creatures look as if they could climb without arms, while still appearing threatening,” says Jenn. “We performed a lot of animation tests and had the idea that the Vivs could use their spiked tails to grip onto the rock as they manoeuvred through the terrain. That helped to physically ground the digital assets into the environment while making the Viv’s movement feel natural within that topography.”

A leap of faith

The FX department supported animation on the Viv creature effects – for example, creating the profligate saliva that drools from one animal’s maw as it roars down at a trapped Judy. The department also helped to establish the creatures’ connection with the environment via interaction effects, such as kicked-up dust, sand and stone, as well as disintegration effects as some sections of rock break apart under the Viv’s weight.

Interestingly, these effects existed not only to ground the creatures into the scene physically, but also to explain the sequence’s vertiginous finale. “We also had to set up an important premise, which was that the rock in this environment could crumble and break easily,” explains Michael. “The reason for this was a key plot point that enables Judy to break free: she leaps across a chasm to escape, and while she makes the jump, the pursuing Viv fails as the cliff edge breaks apart and falls away. As such, the pack can’t continue the chase. We foreshadowed this by adding some key moments during the pursuit, where you can see the Vivs destroying sections of rock as they run. That necessitated some detailed simulations, which in turn necessitated some detailed look dev to match the textures of the rocks on set.”

Image Engine also quite literally heightened the sense of danger for Judy’s final leap of faith. “The rocks on set were only two metres high, but production wanted the ground 80ft below Judy when she made the jump,” says Andrew. “We replaced a whole section of the on-set environment with a cliff and pushed the ground further away, making the surrounding rocks feel like 30-metre tall mushroom stalks. We also carried out several set extensions to allow for wider, more expansive shots.

“This work served to tell Judy’s story and to emphasise the level of threat she must survive. All in all, it makes for a riveting watch.”

Together at last

The final sequence bearing Image Engine’s touch brought the studio’s two main elements together – the robots and the raptorial Vivs.

Episode six finds the Robinsons huddled within a security defence field that’s repeatedly losing power. Beyond the fence’s boundary and the reach of their campfire’s glow sprawls a cloak of shadow, and within it, a pack of encroaching Vivs slowly but surely make their way towards the unlucky family.

Image Engine animated the Vivs, and also emphasised the Robinson’s peril via a claustrophobic and intimidating atmosphere. “It’s a very moody flashlight-lit sequence, where you see only quick flashes of the Vivs and the reflective tapetum lucidum of their eyes,” says Andrew. “The production shot the sequence in the studio, planning to keep things dark and claustrophobic. We emphasised that by creating a set extension and making the shadows completely black just a few metres from the perimeter fence, amplifying that dark and mysterious feel.

“We also needed to consider the flashlights,” he continues. “We matchmoved all the practical flashlights in the plates, then dropped them into the animated shots that view the scene from the opposite direction, mixing them in with some hand-animated beams. We wanted to get creative with how these lights moved and what they illuminated, giving just quick glimpses of the Vivs. Doing so became quite a spatial challenge. We needed to think about the characters and their locations alongside the positioning of the camera, while also highlighting the approaching Vivs in a way that maintained this eerie feel. Working with editorial, we locked down the scene in a way that really illustrates the tension experienced by the Robinson’s.

The scene ends with Robinson’s robot protecting the family from the Vivs, using a beam weapon that emanates from his head. This effect comprised a lens flare-heavy render, one that Image Engine designed to feel distinct and alien when compared to the numerous other lights present in the scene.

Finding the way

Ten years ago, a television project with the scope of Lost In Space season two would have seemed near-impossible. Fully CG robot battles, animated creatures and swirling simulations were the kind of souped-up visuals reserved for cinema. Netflix and the new wave of streaming services have changed things, and visual effects studios have had to keep up with the new expectations of audiences. Image Engine has done so by building a robust pipeline founded in exceptional talent and up-to-date technology, making for a studio capable of tackling projects as complex as Lost In Space within the strict turnarounds of television deadlines.

“The quality that’s expected from TV today is above and beyond anything we’ve seen in the past,” says Andrew. “4K became a new standard in TV even before film, and everything is done in HDR, so you have all these new considerations.

“Nevertheless, Image Engine is well equipped for this new landscape. We’ve built our team, our expertise, and our pipeline to the point where we’re capable of tackling even the most complex of visual effects shots with a tighter deadline. On Lost In Space season two, we knew what we had to do, and we took it all on in a sensible, measured way. The team was like a solid, well-oiled machine; they built up a nice rhythm and balance across the whole project, and we were confident we could final shots and get things signed off without problems.”

But ultimately, Andrew was most happy with the wellbeing of his team. “Television work is undoubtedly more demanding than ever, but when you’re equipped and intelligent about it, you can work at a pace that keeps your team feeling good. And that means better work, which I think shows on the screen throughout Image Engine’s sequences on this epic second season.”