Lost in Space: Season 1 Case Study

Case Study

Netflix’s intergalactic search for home has its roots in classic 60s sci-fi, but the series relaunch needed a modern-day boost. In stepped Image Engine with an exciting brief: re-imagine the galactic adventure using the latest in computer graphics technology. The result is a cosmic experience brought down to earth using the latest in photoreal visual effects, all designed to enhance and augment the emotional narrative…and show robots fighting in space.

Lost In Space is Netflix’s slick, 4K reboot of the classic 1960s TV show. A twist on the time-honoured tale The Swiss Family Robinson, this modern-day update again follows a family of pioneering space colonists tasked with exploring the cosmos in 2046.

When the Robinsons’ spaceship, Jupiter 2, veers off course towards an unknown planet, the family finds they must battle the elements to survive. Things go from bad to worse as the Robinsons become entangled in a death-defying race against time, hopping from one hazardous extraterrestrial environment to another – environments that Image Engine had to create.

Image Engine’s visual effects take centre stage for 266 shots across five stunning episodes. Among other augmentations the studio was responsible for enhancing a lush woodland, creating a raging wildfire, directing a colossal crash, and, of course, building some extraordinary robots.

For VFX Supervisor Joao Sita, the opportunity to refresh the retro sci-fi feel of the original Lost In Space was a dream come true. “It involved a lot of concept art, a lot of shot development, and a lot of fun,” says Sita. “The client was really open to taking feedback and guidance based on our expertise in sci-fi concepts. We were able to be really creatively flexible, which is a dream brief on a show like Lost In Space.”

One of the team’s first jobs was to simulate a beautiful forest. And then burn it to the ground.

Seeing both the forest and the trees

With experience on shows like Jurassic World, Image Engine is no stranger to interactive digital forestry. Lost In Space required the studio to once again bring these skills to the fore, building an alien forest that scaled from individual detail to an overall sense of depth and atmosphere.

Image Engine artists built the full forest in CG. They received on-set plates and LiDAR scans from the production, which provided a rough idea of the size and growth of the trees surrounding the two main characters. The team was then able to replicate this in the dizzying array of digital forestry required for the scene.

“These elements helped to create a digital environment that would be completely seamless with the plate,” says FX TD Michael Billette. “We built on top of that foundation using SideFX’s Houdini – not just the layout, but a lot of the modelling, too.”

The FX team first ascertained the general distribution of trees and bushes. They then simulated branches, positioned logs, and established patterns of growth to match what the audience would see in the plates. The resulting procedural layout was then used to create an optimized render setup. This enabled more unique geometry to be rendered than possible on previous shows.

And there was a great deal of geometry. Artists were working with massive scale, from defining massive variety in the size, angle and height of branches to establishing the placement of needles on plants.

FX Supervisor Denys Shchukin likens the forest construction to a LEGO build replete with FX detail: “We had so many assets. We’d be provided with a set of trunks, big branches, small branches, twigs, leaves and told there you go: assemble your forest however you like! We could add so much detail working in this way.”

Spreading like wildfire

Into Image Engine’s dynamic alien forest wanders the young Will Robinson (Max Jenkins), followed by a robot seemingly hell-bent on murder.

Before the robot can attack, a shocking wildfire rips through the forest, trapping Will in a tree. The robot loses its legs in the chaos, and as his energy fades he gives up his hunt. It seems the fire will engulf them all until Will realizes he can reunite the robot with his legs. In turn, the robot saves Will, bonds with the boy, and takes on a humanoid form as his companion for the remainder of the season (one always ready to warn the young Will of any encroaching danger).

As Sita explains, the otherworldly forest and brutal wildfire were more than just backgrounds. They were a furnace for a pivotal narrative moment: “The forest played almost a character in those shots,” he says. “The fire ultimately cements the relationship between Will and the robot.”

To create fearsome photoreal wildfire, Image Engine used a clever combination of FX, digital matte painting, live action footage, and compositing. As Compositing Supervisor Keegen Douglas explains, DMP played a huge role in augmenting plates already shot by the client: “We were provided with in-camera shots outside in the forest and then we had some studio shots with Will hiding in the tree. There was nothing else around him in the plates, so we had to rebuild the environments to match the on-set photography.”

This work was aided by the reference material shot by the Image Engine team on set. Thanks to this photography, Image Engine’s artists knew exactly how different trunks and twigs would ignite and burn and what the emanating embers would look like. “We developed a library of fire elements and fire behaviour based off of this,” says Shchukin. “That means we didn’t have to re-simulate a different behaviour each time for every shot or every frame.”

Using its DMP work and huge FX element library – along with tools such as Deep and Cryptomatte – Image Engine could easily assemble shots on the fly. “Our temps were super quick,” says Douglas. “That’s immensely helpful, because you can see a shot and present it to the client right away. That gives a visual context. It answers a lot of questions for you, and answers a lot of questions for them, speeding up the whole iterative process.”

“This was so important when it came to the interactive lighting, the surrounding environment, and seeing it all come together,” says Sita. “On top of that, comp could go crazy when adding final detail. We would push the CG elements to a certain degree and from there on it was more about the photography and letting those guys experiment.”

The comp team added sparks, smoke, embers, and up to 70 other 2D elements to 50 FX fires. The compositors had total control over the intensity of the FX fire in each shot too, enabling greater flexibility in dialling in the intensity of the scene. In one case, the compositing team used almost none of the original plate bar a small part of the tree. Everything else was 3D.

“The only thing we added in comp was a little bit of smoke,” says Douglas. “It turned out to be one of the most outstanding shots I’ve seen in visual effects; in TV or film.”

Warming a cold robot heart

Within this intense conflagration occurs one of Lost In Space’s more nuanced narrative events. Class B-9-M-3 General Utility Non-Theorizing Environmental Control Robot (aka “Robot”) softens from aggressive automaton into sympathetic ally, connecting with Will in the duo’s moment of peril.

Image Engine’s animation team needed to convey this subtle transformation through the power of CG. The more the robot’s energy depletes, the more his empathetic character emerges. This was a challenging task, given the lack of dialogue taking place in the scene.

“There’s no conversation happening. It’s all emotion; it’s all in the animation,” says VFX producer Cara Davies. “In reaction to that we had to think deeply about this character and figure out what would make him emote. We really needed to define the characteristics of this robot.”

That required more than just a little creative thinking: “You can film reference footage, but unless you have four arms and pin yourself under a tree you’re always going to need a bit of imagination when working on a scene like this,” says Animation Lead Julia Flanagan. “Animation is an intuitive process, so we had to feel out the scene and the robot’s actions. What was constant was the need to imbue the robot with a continual collapse of energy – a gradual decline that we maintained throughout the sequence.”

Image Engine did this by softening the “heart” of the character. “We would find ways to increasingly depart from the the robot’s sharp, jagged and ferocious aspect as his power drains,” says Animation Supervisor Chad Shattuck. “That meant animating more gentle curves, drooping his shoulders, and making him appear softer and more vulnerable rather than aggressive and predatory.”

Exquisite creatures

Image Engine further communicated the dying droid’s empathetic disposition by visualizing his relationship to nature. During the sequence, an exotic, alien butterfly floats down onto the robot’s hand; an entirely CG creation crafted by Image Engine’s artists.

“The production wanted the alien butterfly to appear as if swimming through the air – akin to a rippling, airborne sea slug,” says Shattuck. “The challenge was that sea slugs move parallel to their ripples. Butterflies move perpendicular to their wide wingspan.”

The animation department resolved this contradiction using maths. Firstly, they created 1,000 joints to pump the butterfly’s wings. Next, a procedurally generated sine wave motion created biologically believable ripples that undulate across the creature as it flies.

When the butterfly lands, its wings fold and envelope into themselves. This animation was completed by hand so as not to compromise the creature’s exquisite grace. “It’s basically stop motion, with work on every frame,” says Shattuck. “Once the work was complete, this gave us a fold up and fold down that we could then use anywhere, anytime. It was a stable and reusable animation that we could always layer with added work if needed.”

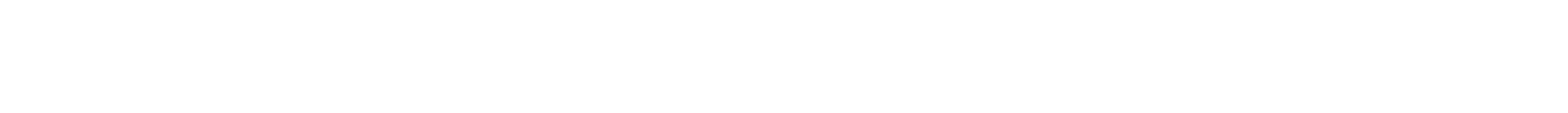

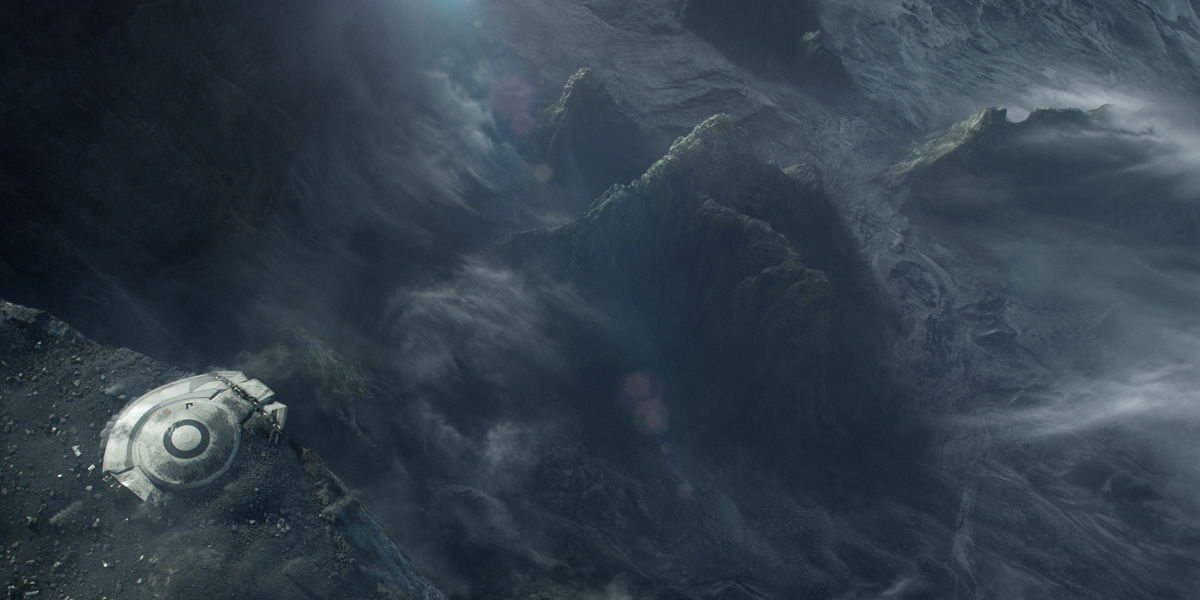

A colossal crash

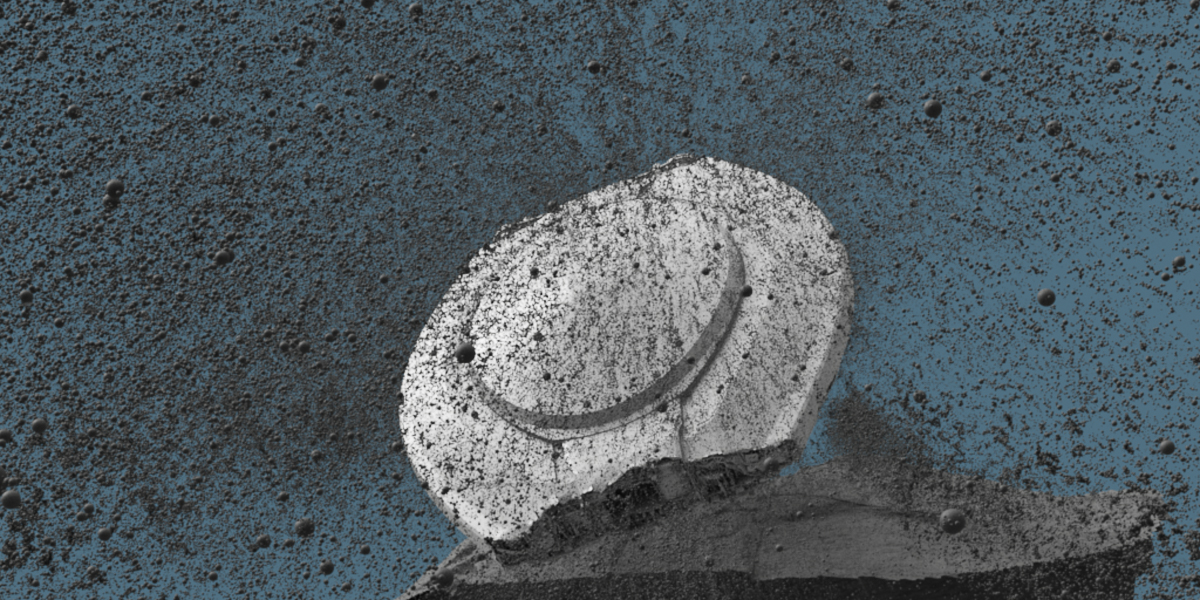

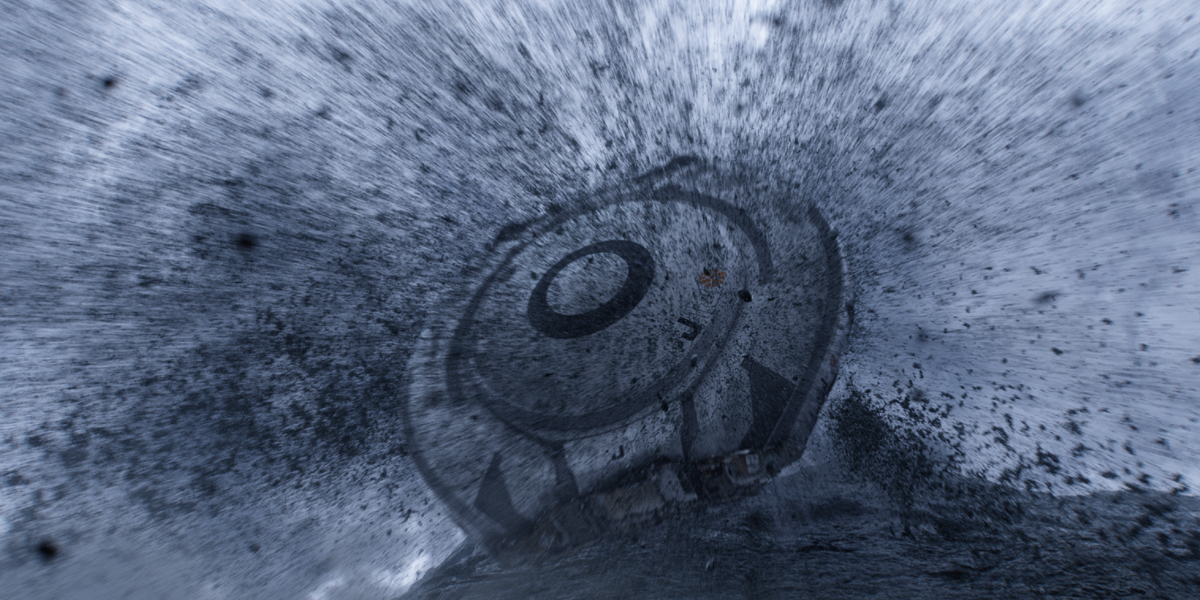

Another sequence in the season sees another Jupiter crashing violently into the top of a cliff before plunging into the depths below. Image Engine needed to make the sequence feel as physical and visceral as possible, communicating the weight of this massive craft as the surrounding environment is torn apart and gravity beckons it into the depths.

“The production shot the sequence in a quarry. It was the environment and FX teams’ job to augment the plates and enhance the themes of drama and discovery,” says Sita. “The production was keen on achieving a natural look, but one that would also tell the story the sequence needed to tell.”

Image Engine’s environment team built assets for the cliff wall and the crash site, while FX worked on the spaceship’s collapse from the cliff. The team developed a major simulation containing millions of particles, representing the dirt and pebbles that cascade from the cliff alongside the spacecraft. And all of this before the receipt of final shots.

“One of the most challenging aspects of the sequence was that we commenced work without possessing full reference. We didn’t know where the ship would be in the shots or how fast it was travelling,” says Sita. “As such, we needed to create a very brief sim and layout for each shot. From layout to assets to FX to light to comp, every department had to first create a shot to see if it could work.”

Upon receiving plates from production, the team found some shots ventured too close to the ship to use the FX system the team had developed. A finely tuned, handcrafted solution was developed in response.

“We manually animated the triggering of elements breaking apart and sliding off,” says Billette. “There was also a close-up shot from the top where we had to integrate FX into the plate and extend the plate from a close distance.”

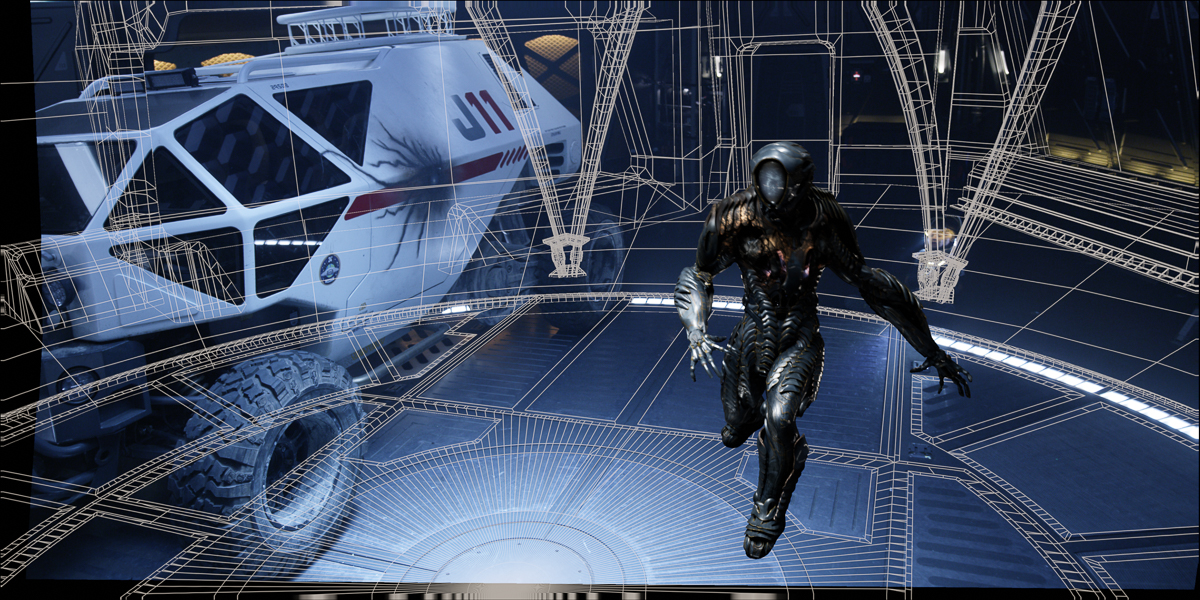

Robot battle royale

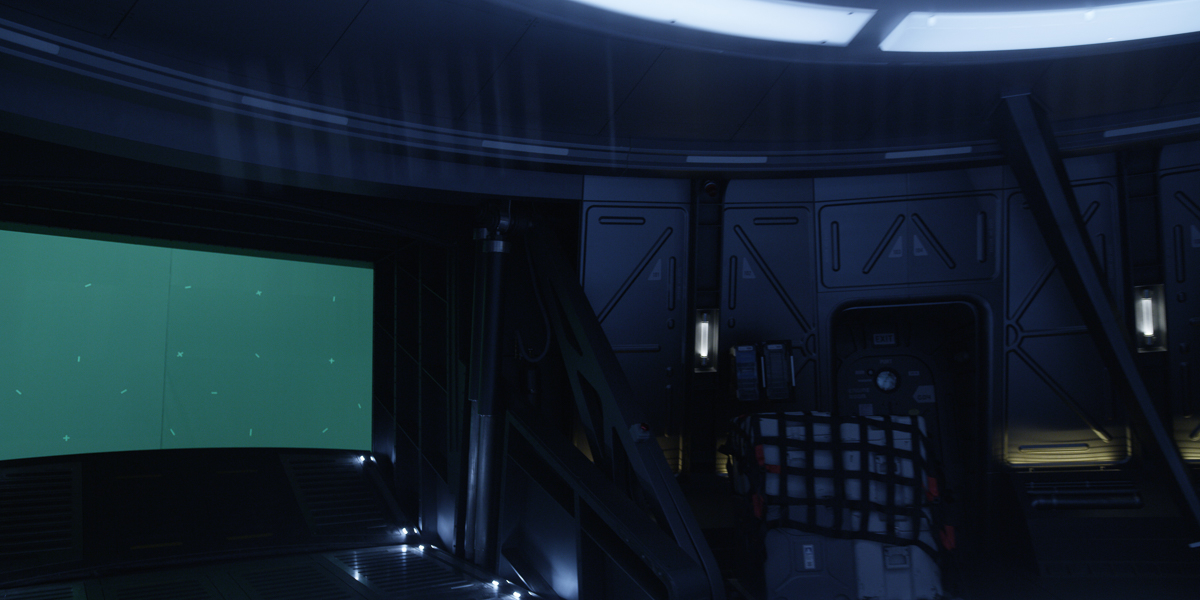

Lost In Space’s first season culminates in a spectacular battle – a high-adrenaline clash between Will’s companion robot and his malevolent counterpart. In space. With lasers.

“We were heavily involved across the sequence, even elaborating on the script from the previz stage,” says Sita. “The script was incomplete at that time; they had a one-page description of sorts and were yet to flesh out the details. However, it was a very dynamic production; they were always looking for us to pitch new ideas and concepts…so that’s what we did!”

Sita formed “a guerilla team”, complete with Shattuck and Flanagan. All three donned mocap suits and acted out a first blocking of the space battle, sharing the results with the production. “As we were solving the logistics of the fight we were also essentially writing the script for the battle at the same time,” adds Shattuck.

Shattuck’s team then set about animating the robots. An initial challenge arose in the discrepancy between the human-esque and yet inescapably robotic nature of the companion robot. Image Engine’s animators needed to strike a balance between the two in its fighting style.

“Even though he’s performing a fairly human motion, he still has those echoes of being a robot,” says Flanagan. “We continually brushed in small elements and movements that added to the subtle robotic foundation of the character.”

Face-melting metal

The battle is action packed indeed, with the two robots fighting tooth and nail (or rivet and screw) for survival. Image Engine created numerous damage elements on both robots, gradually revealing the injurious effect each has on the other. But they saved the biggest punch for last: the climax of the fight arrives when Will Robinson’s companion robot unleashes a white-hot fist, launching it into his enemy’s face and melting it in the process.

The talented Image Engine FX team stepped in once again, setting up a simple simulation and then layering it with seven layers of intricate FX. “There were sparks, droplets of hot metal, spraying incandescent fluid, and more besides,” says Shchukin. “We also needed to produce many elements of steam emanating from the hand, which further grounded the effect in reality.”

The team maintained the volume of molten liquid from shot to shot, not only from the hot hand itself but also from the resulting smashed visor of the punch’s recipient.

It was one effect of many that made up Image Engine’s impressive body of work on Lost In Space.

“The quality of work was just so high across every shot delivered. It had to be for such a passionately developed reboot,” says Shattuck. “Whenever a character or digital asset was composited into a shot, it truly looked like it was there, within the physicality of the scene. It’s an exciting level of detail for a television show. No expense was spared.

For Sita, the experience working on Lost In Space was nothing short of phenomenal. “The Image Engine team had an incredible amount of fun in working on this project,” he says. “We were not only given a lease of creative freedom on rebooting the aesthetic of a sci-fi classic, but were also able to pitch new ideas and concepts.

“It’s incredibly rewarding to have that kind of influence. Especially on a core new Netflix release that is sure to win the Lost In Space series a host of new fans across the globe.”