The Meg Case Study

Case Study

Jaws has long reigned as royalty in the fathomless oceans of cinema. But even Spielberg’s iconic great white has nothing on the 70ft Megalodon striking thalassophobia into the hearts of the public in Warner Bros.’ The Meg.

The titular, long-thought-extinct “Meg” is primed to join the pantheon of classic movie beasts. It’s an intimidating creature, its size reducing human beings to relative tadpoles; Jaws to a common goldfish.

Naturally, a monstrous threat deserves a proportional response – and who better to lead the charge than gung-ho action star Jason Statham? Statham takes on the role of Jonas Taylor, a former Navy captain who sees a shot at redemption in bagging the prodigious predator.

Image Engine bravely entered the waters alongside Taylor to support and augment director Jon Turteltaub’s vision. The team enhanced 147 shots across 10 sequences, which included a submarine launch and look development on the nautical depths witnessed beyond the submersible’s viewports.

Read on to learn how the studio battened down the hatches and got to work on several key sequences, bringing the big-budget, shark-hunting spectacle into shipshape fashion.

Making a splash

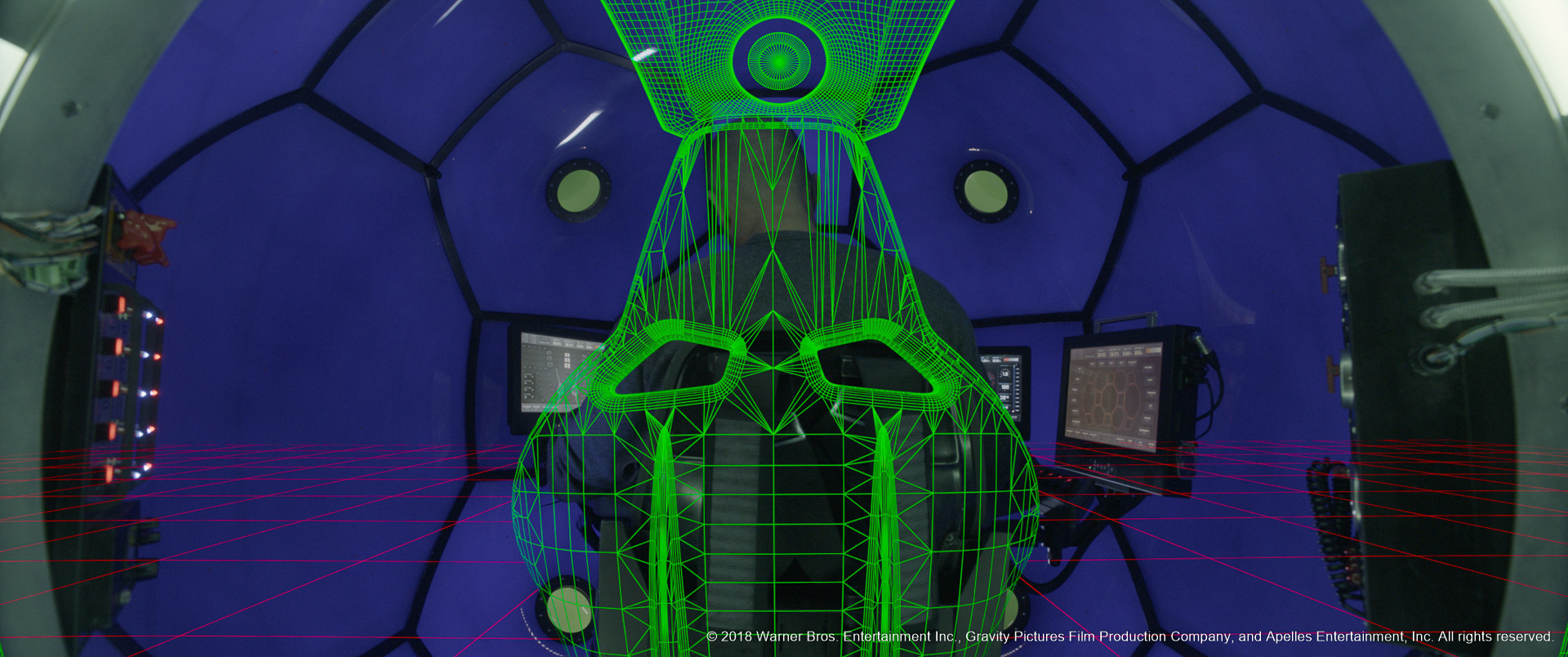

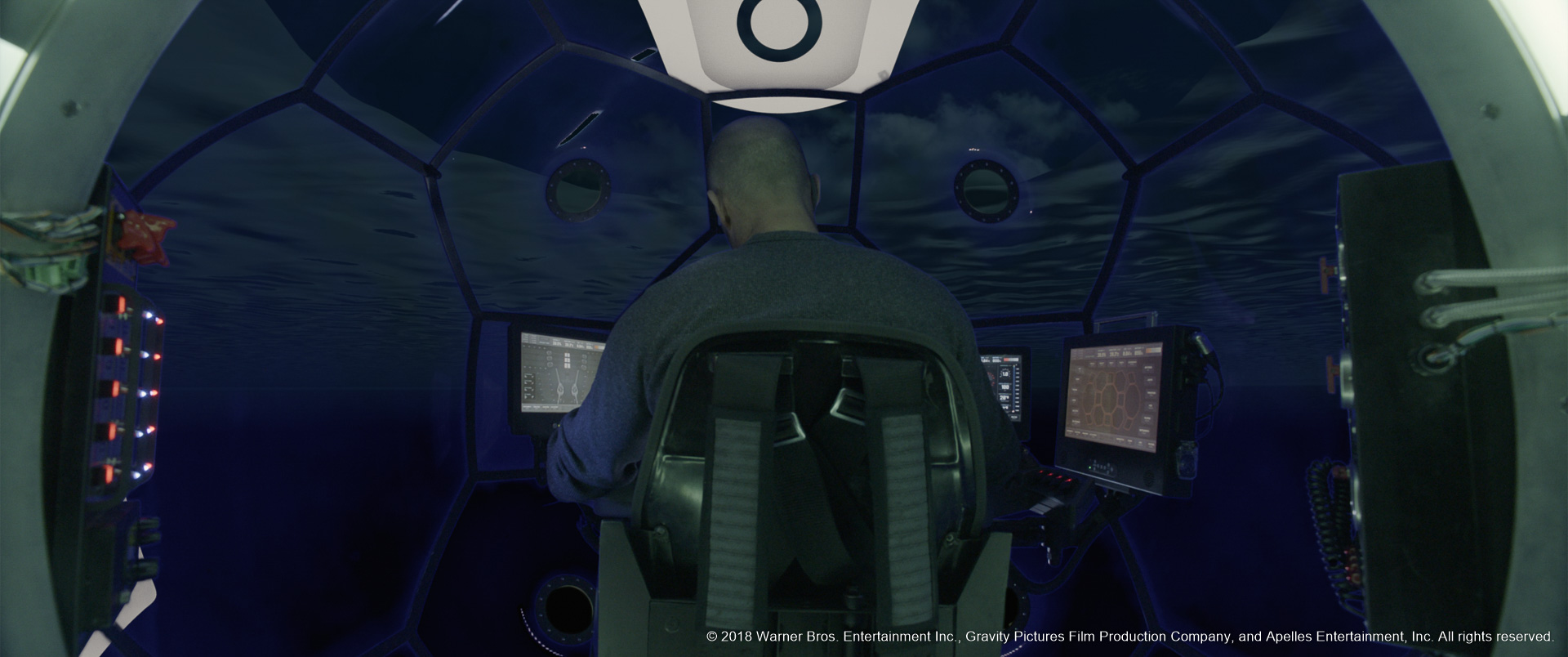

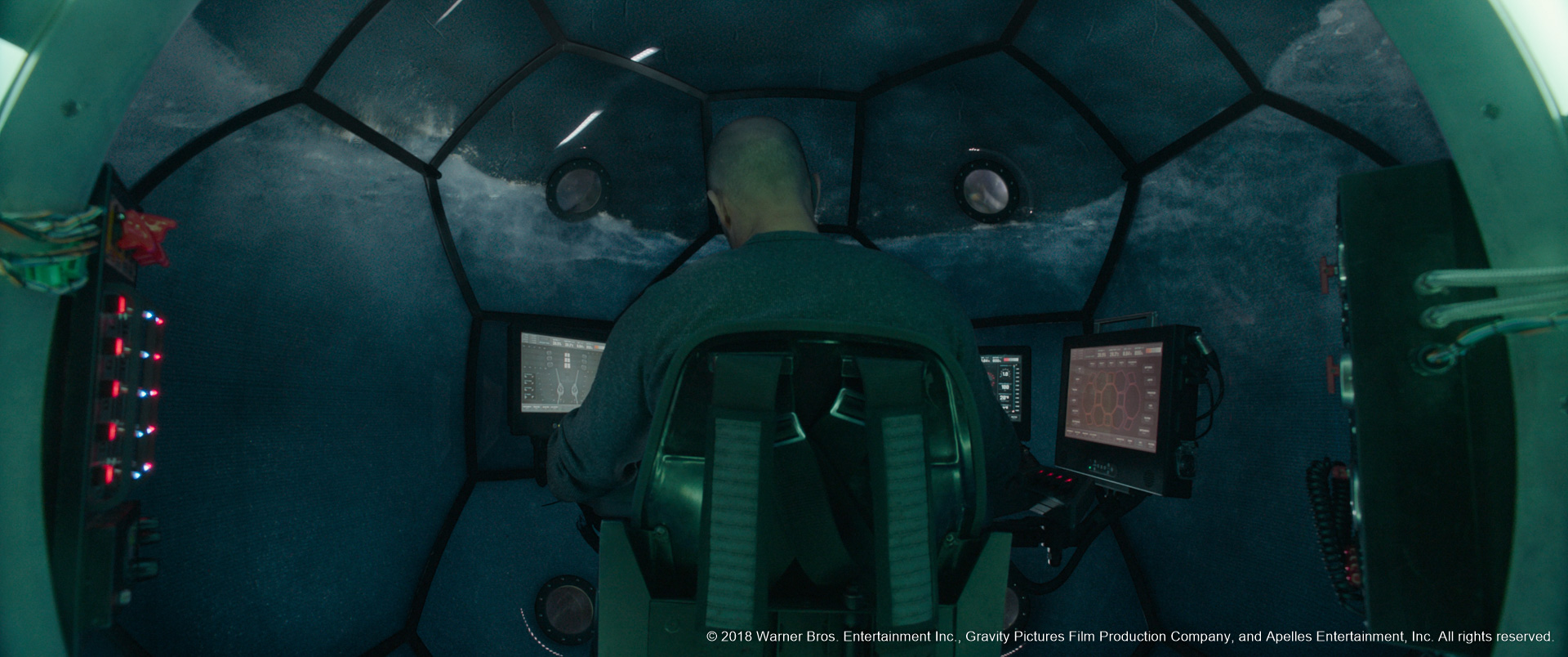

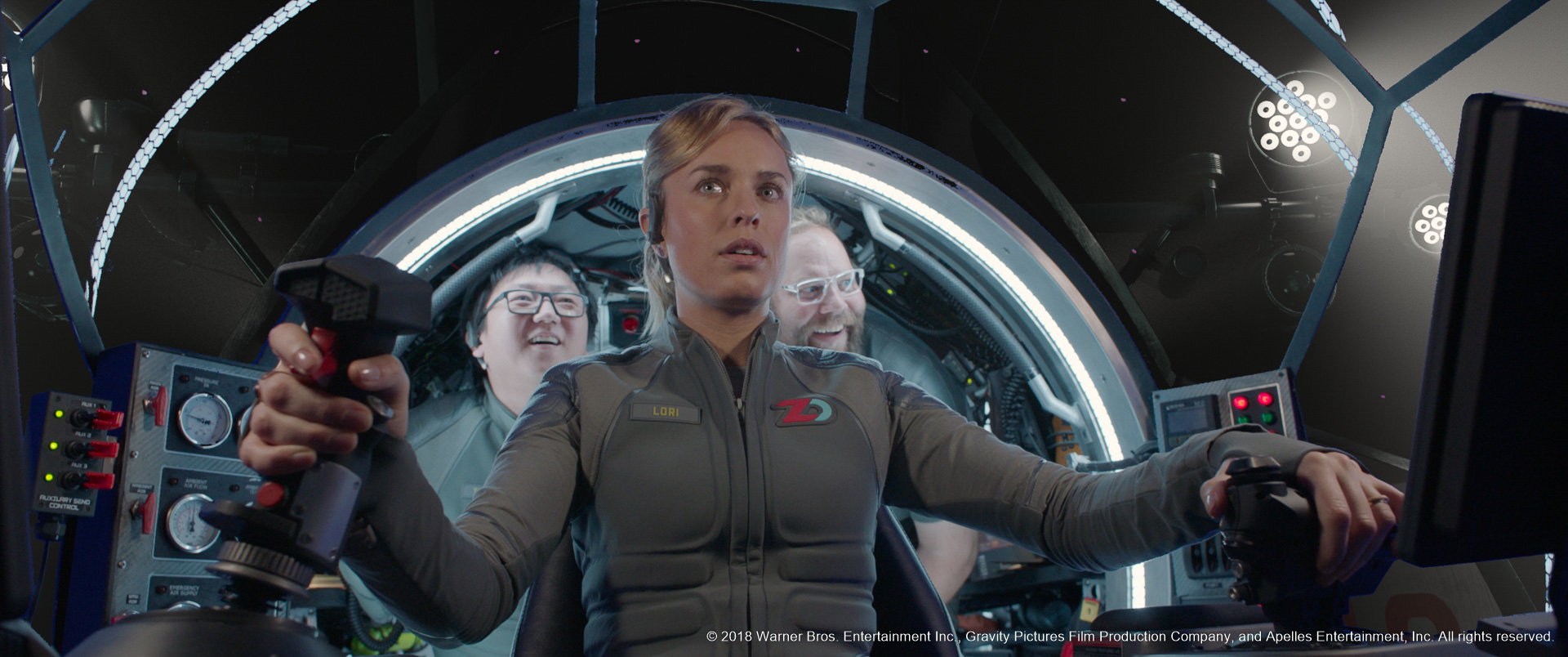

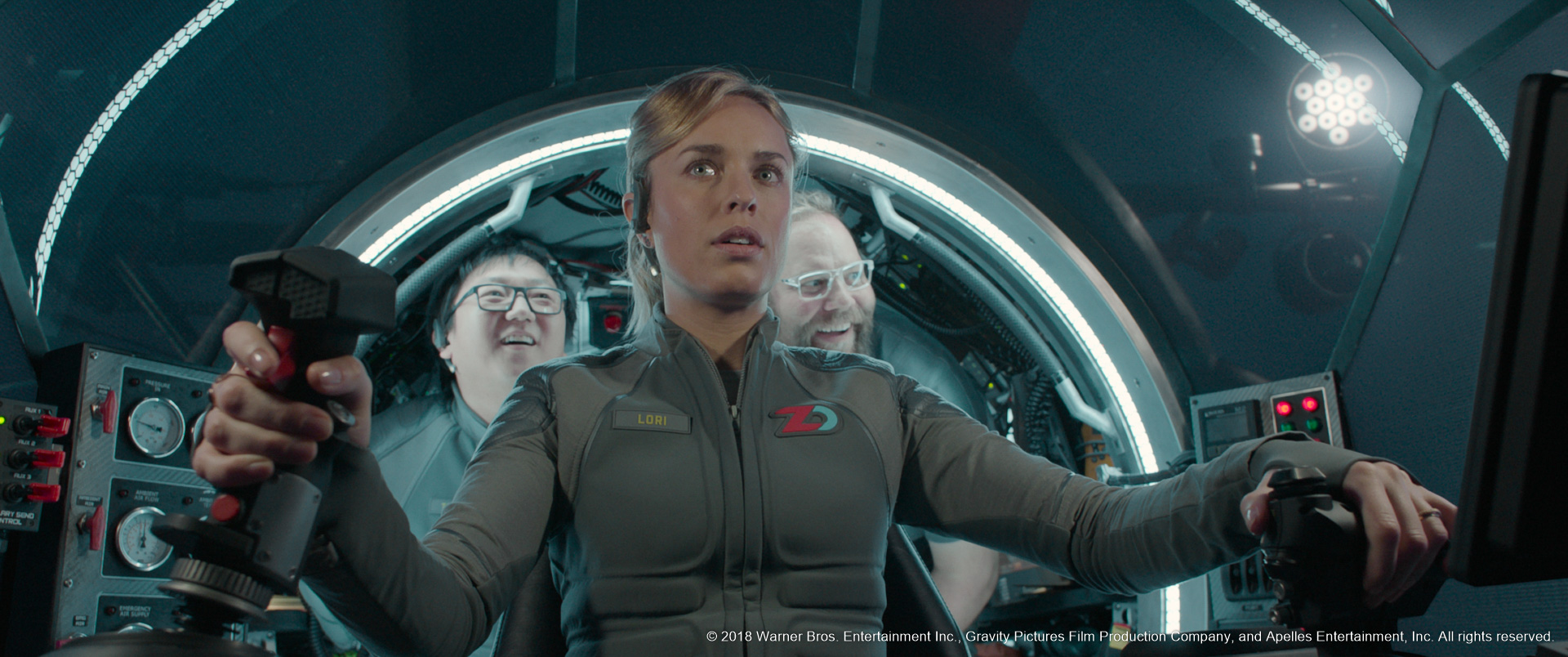

Image Engine’s key shot on The Meg sees a submarine dropped into the ocean, with the audience perspective set inside and looking outwards through a 360-degree spherical dome. This sequence necessitated a complex blend of water and light simulations, each meticulously designed to feel completely believable and sell the intensity of the scene.

“Firstly, we had to consider the digital waves on the ocean surface, and get that feeling locked in of foam and bubbles and the transmission of light into the surface of the water,” begins Martyn Culpitt, Image Engine’s visual effects supervisor. “Even when you’re looking at the surface there’s a depth to water, which we needed to communicate.”

Image Engine has plenty of previous experience with water FX, with numerous sequences delivered on projects such as Independence Day: Resurgence, but the integration of surface fluids, submersed shots, and splash work in The Meg presented a new challenge. The team spent ample time on research and development, ensuring the effects of the submersible launch reflected the real-life physics of a large object interacting with a body of water.

“We needed to communicate that sensation of dropping something hollow into water,” says Culpitt. “It doesn’t just sink but drops, floats up, and bobs around. We needed to make sure that the audience felt that sensation as if they were inside the craft themselves, while also ensuring the digital water simulations were realistically reacting to these shifts.”

Crafting the perfect reaction required intense computing work. Simulating a full ocean view was deemed too time and resource-intensive for the shot, so the Image Engine team found a useful workaround that would deliver high quality results within the required timeframe.

“We created a container of digital water within the camera’s field of view, which had a great deal of resolution within it,” explains Culpitt. “We then figured out a way of blending this with the spectrums of movement of a lower-res ocean surface farther away from the camera. This allowed us to focus more closely on the details of what was happening next to the viewer, rather than what was happening in the far distance.”

In addition to the water simulations, Image Engine focused on the interplay of light and water. “Without believable interactions between the boat and surface, the shot wouldn’t look right,” says Culpitt. “With this in mind, we added projections of caustics from the ocean surface refracting on the side of the boat, which make it feel like the craft is really sitting there. We used lots of reference of submarines and how water would move around them to lock in these details and deliver something that felt physically believable.”

In deep water

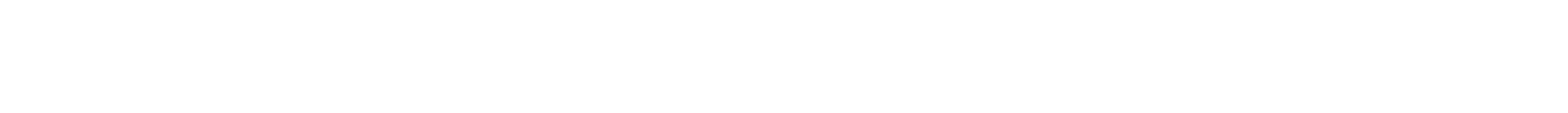

Upon making splashdown, the submarine descends to the depths hidden below the surface. Image Engine needed to generate the murky abyss encountered by Taylor and co, but with a twist: the view outside is presented not through glass or portholes but by an array of screens, each displaying footage from individual exterior cameras.

“There are probably 20 screens showing footage from outside of the craft,” says Culpitt. “We not only created the imagery that the cameras were transmitting, but also the sense that there were a lot of them, in that each screen has a slight offset and reveals a slightly different view of the deep-sea environment outside.”

To create that environment Image Engine needed to fathom out how light pierces down from the surface and how particles move in slowly shifting waters.

Instead of running a full particle simulation, Image Engine used The Foundry’s Nuke compositing software, which enabled the team to easily adjust each individual particle as needed. “Nuke gave us control over every particle, and therefore over the scene at large. We could direct how everything was moving, right down to the finest details.”

Culpitt recalls one experience working with visual effects supervisor Adrian De Wet. Image Engine initially made temporary versions of some shots, delivering quick tracking of plates in Nuke of ocean particles and other effects. They were meant to help guide the process for separate, final shots, but De Wet was so impressed with the initial work that he encouraged the team to finalize those versions instead of starting anew.

“We built that trust,” says Culpitt. “Adrian said if we think they’re final, then send them through, which was a profound statement of belief in the team’s work.”

The studio’s work on this shot also exemplifies its collaborative approach to VFX. Image Engine worked closely alongside Double Negative, one of the primary vendors on The Meg, in bringing the scene’s assets to life. Indeed Steve Garrad, Double Negative visual effects producer, trusted the Image Engine team to provide their own take on work and even expand upon shared shots.

“DNEG gave us scripts that they had created, and we mimicked what they’d done to bring consistency to the sequence and lock it into the aesthetic of the film,” says Culpitt. “Working with other studios is an important part of the process, and one we always enjoy. We all know what is needed from the tools and how to get a shot working. It’s always eye opening to work alongside another talented team to deliver the best possible results.”

Pushing out the boat

Image Engine contributed additional work to numerous other sequences throughout The Meg. These included adding a CG boat extension to a partial set build in a water tank, and then adding CG water simulations interacting with the asset. Elsewhere, the team added CG water droplets to actors’ faces, and altered the look of screens to give them a reflective, iPad-like quality.

“Some of our work was of the more subtle, invisible variety, but this is just as important as the shots of the Megalodon itself,” says Culpitt. “If the effects aren’t invisible – especially when it comes to things like water simulations – it’s going to cheapen the experience of the film. Even when you see the monitors revealing what’s outside, that has to feel real, with bubbles and other details moving past the camera. These are not fanciful effects – they embed the fantasy of the film in reality.”

Pouring effort into these shots, and delivering across numerous complex water simulations, has pushed the Image Engine pipeline even further. The R&D performed for The Meg further establishes the facility as one capable of delivering stunning FX alongside the creature work for which it is famously known.

“We pushed our pipeline forward an incredible amount to handle the physically believable ocean and water surface integrations and simulation,” asserts Culpitt. “With every project, we push the studio forwards in leaps and bounds. The Meg stands as another example of the visual effects Image Engine is capable of in an already diverse wheelhouse.”