Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald Case Study

Case Study

For visual effects artists, it can be a dream to work on a project that can really capitalise on all their skills. That’s exactly what the dramatic opening sequence of Warner Bros. Pictures’ Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, the latest in the Wizarding World and Harry Potter series of films, represented to the artists at Image Engine.

Set in a stormy 1927 New York, the opener sees dark wizard Gellert Grindelwald (Johnny Depp) being transported from the Magical Congress of the United States of America (MACUSA) building across the city aboard a flying carriage pulled by winged Thestrals and accompanied by broom-riders, before he makes a daring escape. With period city views, a flying carriage, broom-riders and creatures, rain and water simulations, and even a character transformation, Image Engine had its work cut out to complete the entire sequence.

Luckily, the Vancouver visual effects studio had already experienced the demands of the Wizarding World, having previously delivered several crucial creature shots for Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. It was on that film that Image Engine collaborated with director David Yates and visual effects supervisors Tim Burke and Christian Manz, who then asked the studio to return for The Crimes of Grindelwald.

Enhancing the action

Knowing they’d need to muster all their recent experience in delivering large environments, animated creatures, and photoreal CG humans, Image Engine visual effects supervisor Martyn Culpitt and visual effects producer Cara Davies gathered a team of artists fresh off other challenging projects such as Logan, Game of Thrones and Lost in Space and began tackling the New York scenes.

Beginning in August 2017, a crew size of around 130 at Image Engine worked on the opening section of the film for 13 months. “I think it is one of the more complex scenes we’ve tackled here at Image Engine,” says Culpitt. “It’s an amazing sequence and we’re all really proud.”

“We also got to invest a lot of time up-front in development, especially in animation and effects,” adds Davies. “I feel that really helped the team figure out a lot of the challenges early on in developing ways to provide automatisation of effects. It feels like such a continuous sequence.”

Digital humans ride again

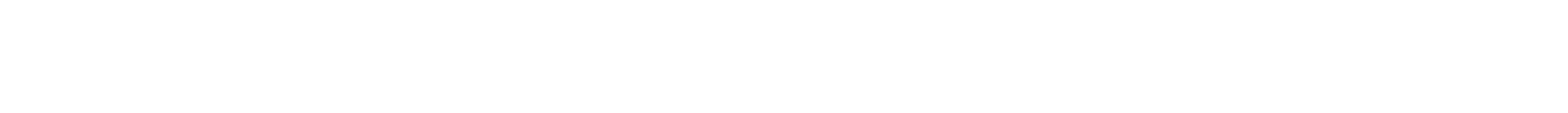

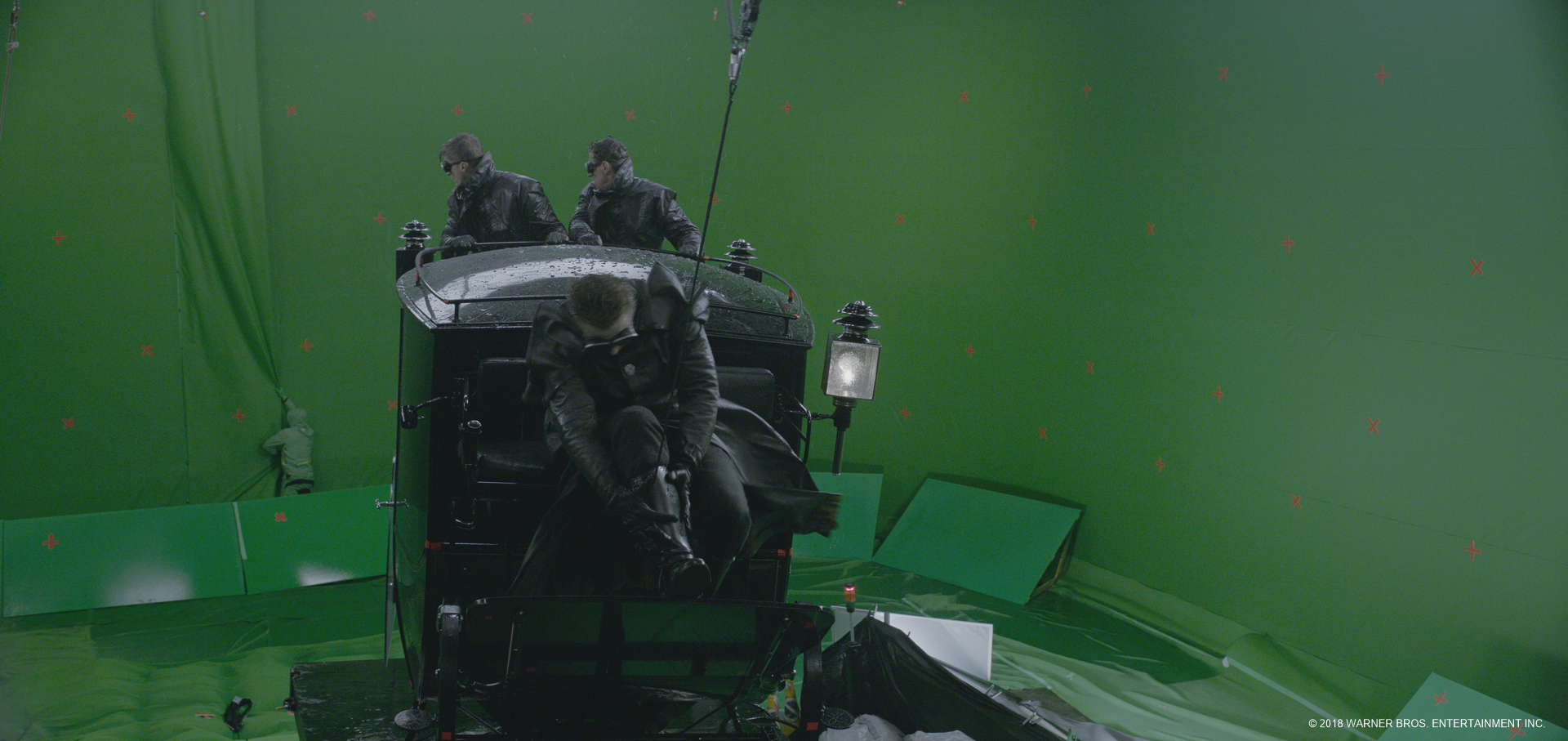

A feature of the New York carriage flight is that the filmmakers looked to capture as much of the action with the actors as possible. This involved filming scenes on stages at Leavesden Studios near London. Here they built several real carriages to perform scenes on, as well as specific stunt rigs to capture the broom-riders, a common element of the Wizarding World.

Using these live action elements as major reference and a guidance for the final scenes, Image Engine would ultimately build the carriage in CG and use this version in the final shots, since it had to appear as if it was being pulled by Thestrals in the rainy environment. The broom riders, too, were captured on elaborate flying rigs against greenscreen. Artists at Image Engine used several of the real riders, or just their faces, in the final shots, as well as crafting digital riders to supplement the shots and add in complex flying moves.

“The characters were filmed on harnesses and rigs on a greenscreen,” explains animation supervisor Jeremy Mesana. “The initial thought was that we were going to use their performances as we shot it and composite them in as elements. But as we started doing some of the full CG shots and adding a lot of dynamic motion to the characters, the client wanted that to be brought into the surrounding shots. So we ended up having to replace them in certain shots to go full 3D to get different motions and angles on them.”

Indeed, Image Engine continued to innovate on its groundbreaking digital human characters for the CG Hugh Jackman characters in Logan. The work in Grindelwald started with the actors on set, who were scanned and heavily photographed for reference, including in faux flight.

“Having the characters there was great as it gave us motion we could start from,” notes Culpitt. “Then we built on that for animation. There’s also a lot of clothing work that we’ve pushed here in terms of cloth simulation. For that we used a tool called Marvelous Designer where you actually stitch the clothing together and then it simulates the movement of that clothing properly. It’s really helped.”

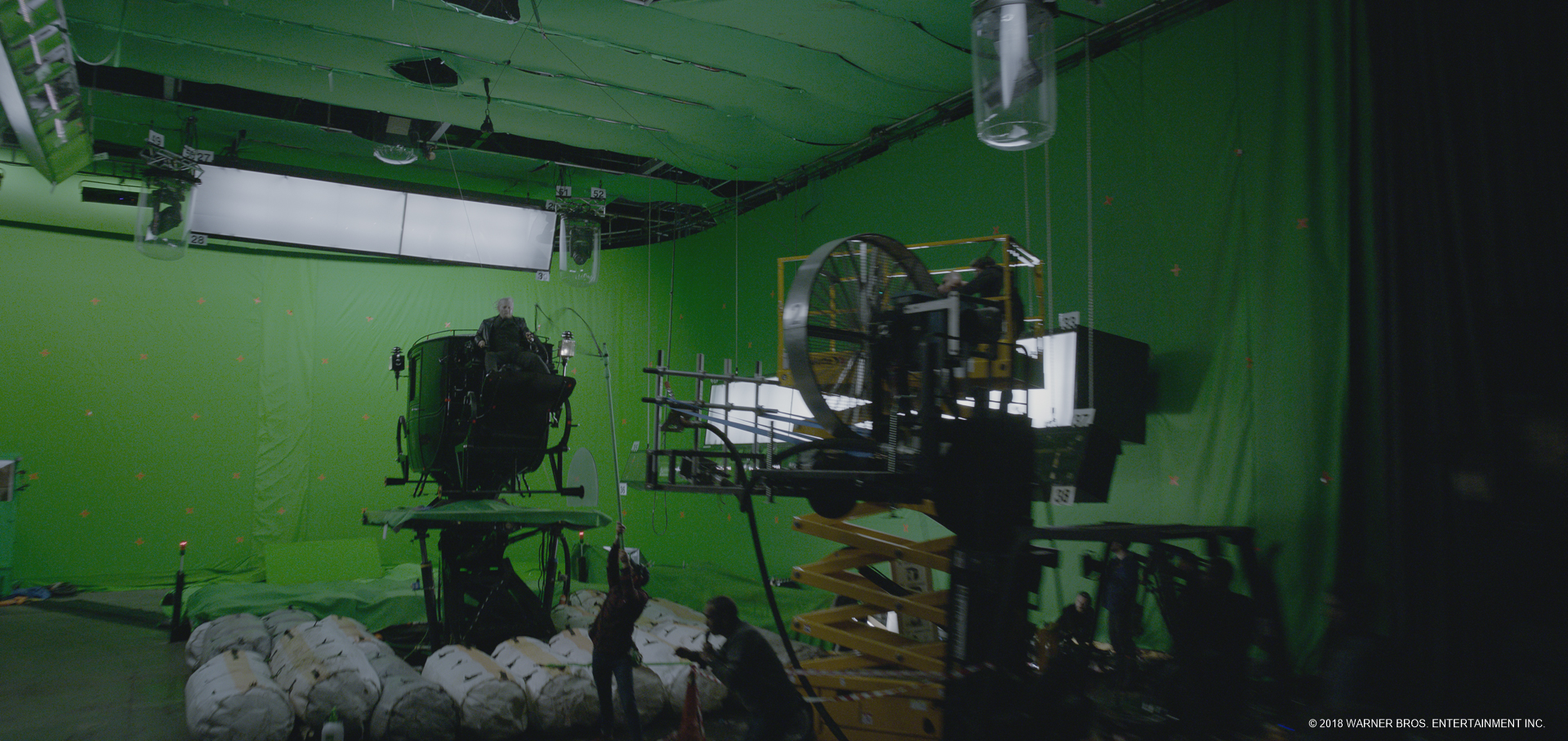

Even more elaborate digital human work was required for a couple of shots in which the character Abernathy (Kevin Guthrie) transforms into Grindelwald. The dark wizard then takes control of the carriage and the Thestrals. Using scans of both Guthrie and Depp, Image Engine built up full digital doubles of the actors and orchestrated transitions that even showed hair growing the necessary length. “We’ve learnt a lot from doing Logan and previous shows,” says Culpitt. “We got to a final result relatively quickly.”

Crafting classic creatures

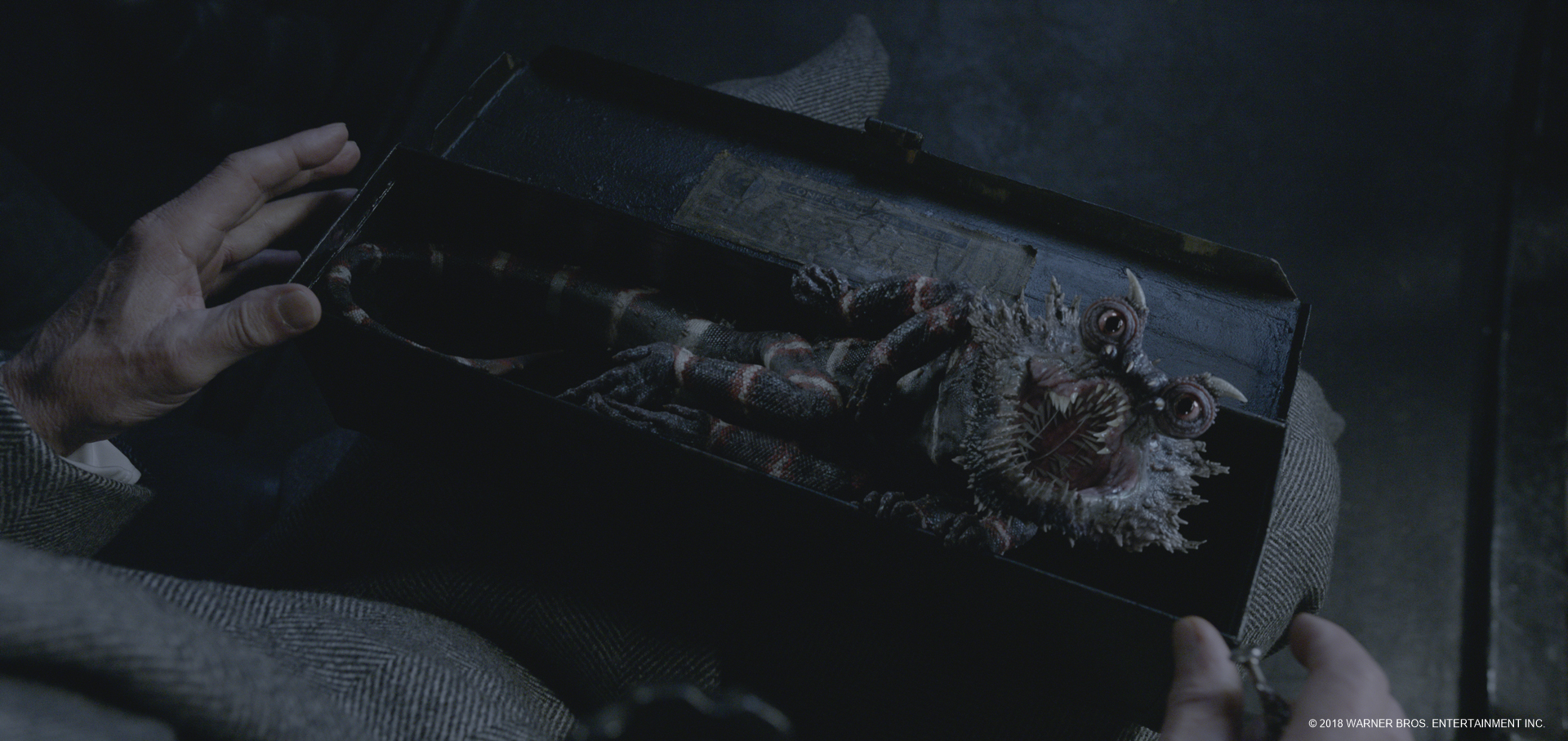

A Fantastic Beasts film would not be complete, of course, without some incredible creatures. One of Image Engine’s major challenges for the carriage scene, aside from the flying winged Thestrals, was the quirky six-limbed spiked chupacabra, although initially the studio was only called on to feature it in a few shots.

“They loved him so much there’s now 13 shots,” says Culpitt, who points out the character turned into a comic relief in the sequence. “He evolved, too. He used to be orange with stripes, and now he’s black with white and red stripes. He’s quite a fun little guy.”

“Its number of limbs was always a bit of a challenge to animate,” says Mesana of giving the chupacabra motion. “We need to make it look like it’s believable and that it could possibly exist. So, as we always do, we take a lot of guidance from different types of lizards and other animals so that we can get some real life reference to help sell the motion.”

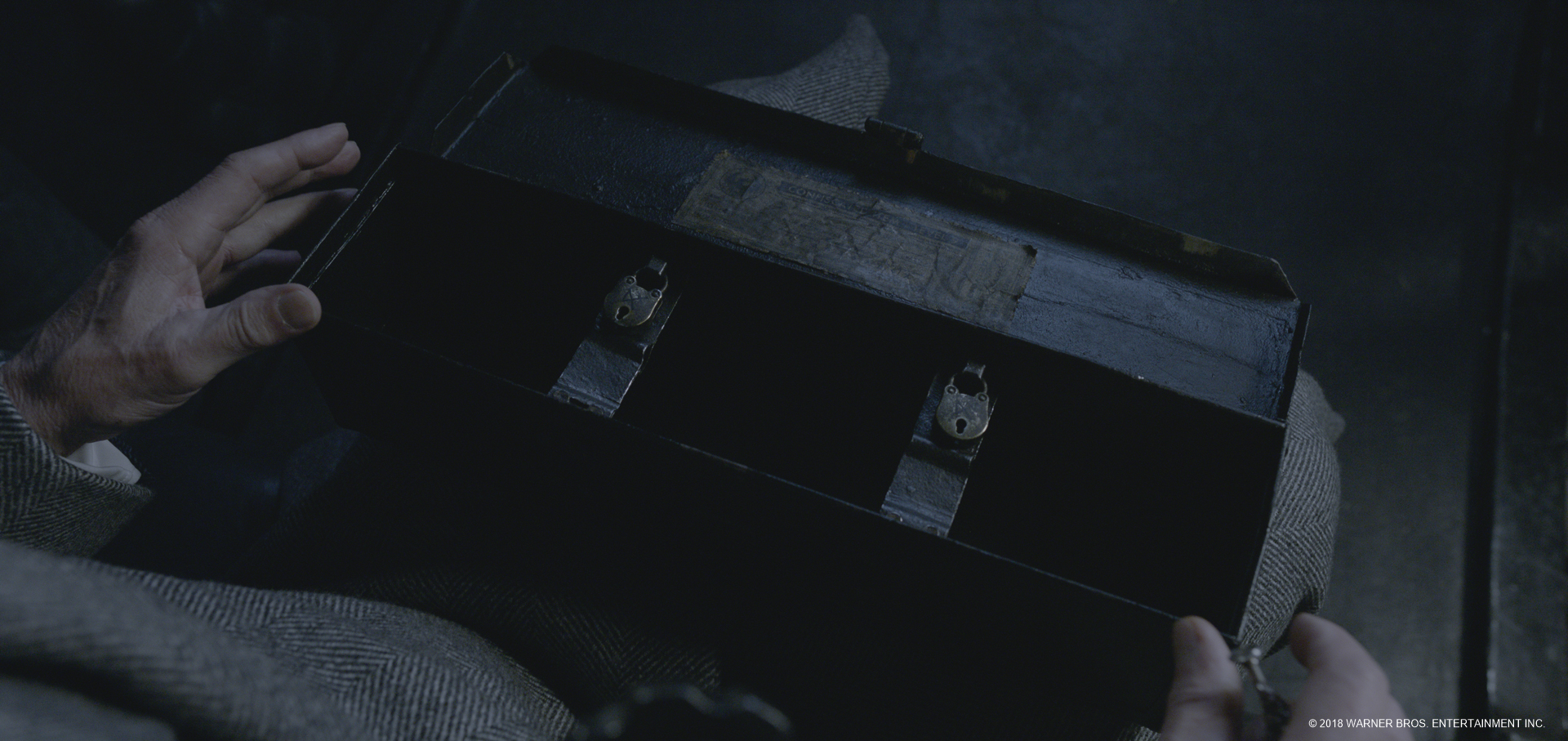

On set, Depp – who, it turns out, keeps the chupacabra as a pet, performed with a green stuffie – “It was dubbed the burrito,” points out Davies – requiring Image Engine to replace the stand-in with a CG version.

This involved meticulous work, according to compositing supervisor Daniel Elophe. “We’d clean-up the stuffie, then we’d matchmove Johnny’s hands to get proper shadow interaction. And then we’d rotoscope his hands and place his hands in ‘deep’ so that everything was deep compositing. It was pretty fun work.”

Through rain and water

With character and creature development under their belt, Image Engine could move onto another signature aspect of the sequence; the fact that the carriage makes its way above New York through rain. Realising the fluid parts of the shots was a big step forward for Image Engine, which implemented the ability to “cascade and auto-generate a lot of water based on the characters themselves,” outlines Culpitt.

“We built the effects sims based on how rain, mist, volumes, clouds and particles would act when hitting an object and flying through the air,” adds the visual effects supervisor. “Once an animation was complete we could just hit ‘auto generate’ and it would run through all the effects sims cascading through them. It would do one after the other, even based on each other if necessary.”

FX supervisor Denys Shchukin oversaw the way that water and rain would be implemented in this cascading manner via the effects simulation tool Houdini. “We realised it was physically impossible to keep running it shot by shot,” he says, noting that this was part of an ongoing automatisation and library-tisation of effects project at Image Engine. “So first we created generic elements and then put it in an ‘uber’ set-up where, once animation was approved, we could automatically run the cascading through our rendering system in Arnold.”

The look and feel of the rain washing and whooshing past the flying carriage and characters and creatures was so crucial to the believability of the scene, that Image Engine had their cascading water simulations also work where a live-action version of a flying character was used in the final shot. “So even if it ended up being a character from the live-action plate,” describes Shchukin, “we still made a full CG character to enable us to layer in CG elements like effects rain.”

City-building

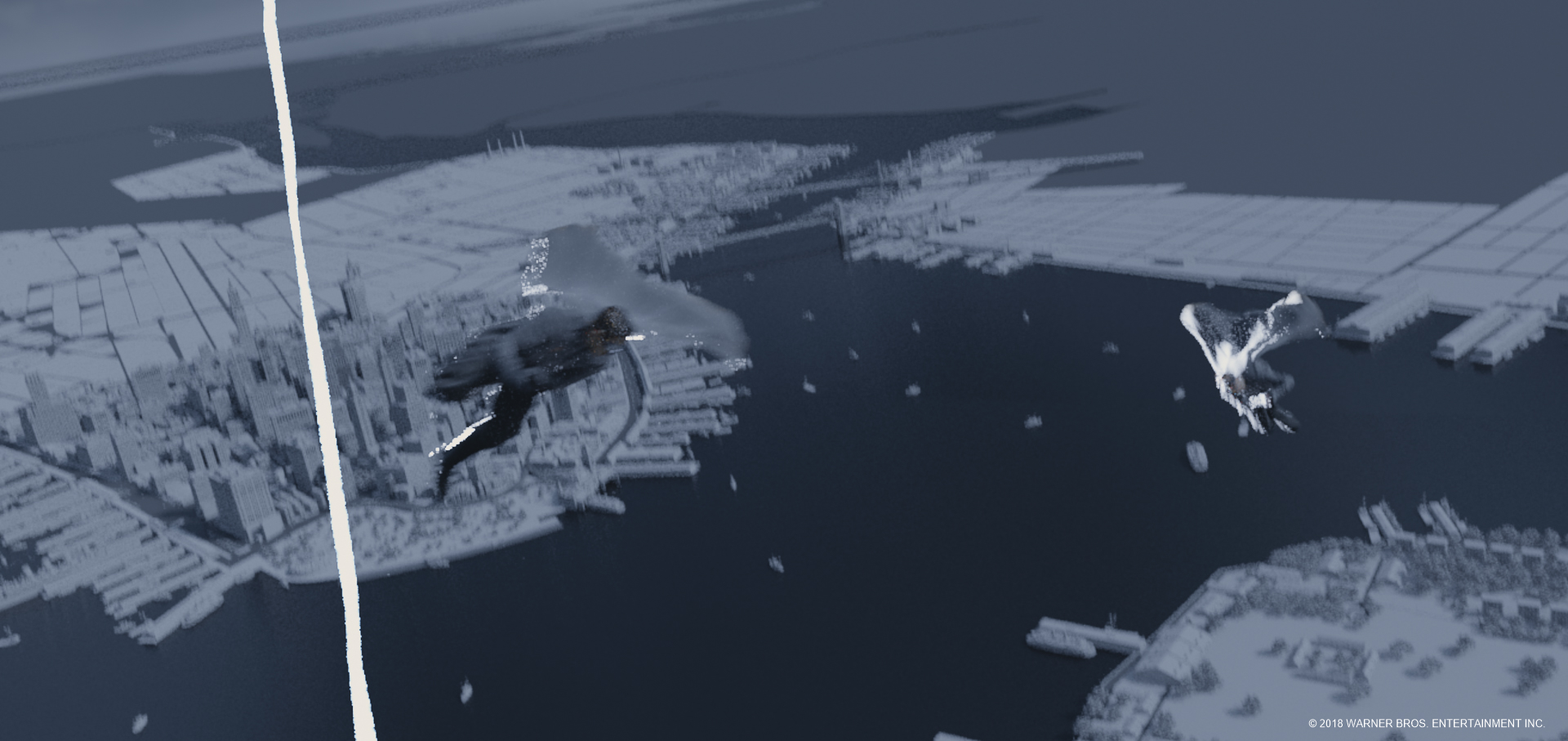

All of this action takes place above a vast view of 1920s New York, a landscape Image Engine built from the ground up based on period reference and available digital maps. A major help in pulling off such a large environment for the carriage to fly through was that the studio’s own early animatics of the sequence were fed back into the postvis done on the production side.

“We had created a version of New York and created a big layout pass,” outlines Culpitt. “We actually fed that back to the client and they updated their postvis with those scenes. So it was a really big collaboration with them.”

Many buildings and New York areas were hand-modelled with hero elements, while outer areas were done with procedural means in Houdini. There was also a traffic system developed to add in moving vehicles to the city streets.

“Using street maps,” details CG supervisor Edmond Engelbrecht, “we were able to look at the footprints of today’s buildings and try and determine how to fit our building library to that. In certain areas we would determine a certain percentage of mid-rizers or smaller townhouses. So that allowed us to get quite a similar look and feel to the time period.”

“And then we had many re-uses of the same buildings,” continues Engelbrecht. “We’d spin them around or do variations of shaders. Because we’re instancing them, we’re not holding all that stuff in memory. You can have one building that represents all those other ones that then gets referenced at render time.”

A storm is coming

That build process provided the geography of New York, but Image Engine also had to implement a particular kind of stormy feel to the scenes. Some of that look actually came from a trip Culpitt had taken as he flew into Wellington, New Zealand.

“He took some photographs and footage of that,” says Elophe. “You notice when it’s foggy and rainy that there’s a lot of light bleeding through things. In NUKE, we’d populate fog boxes around near camera or far away from camera just to take the city light pass and blur it and bleed it to get that light balance.”

In addition, artists created a system for adding lightning bolts that timed with flashes built into the live-action plates. And the studio devised a new workflow for delivering realistic clouds using a combination of Houdini, Image Engine’s in-house open-source Gaffer toolset, Maya and Arnold.

“It was a great way to get clouds done quickly,” says Culpitt, “but it also meant we could have a cloud actually move and have the Thestrals and carriage fly through it and react, knowing that that cloud would match exactly one of the clouds we’d made initially.”

Every trick in the book

After 13 months working on The Crimes of Grindelwald’s opening New York scenes – alongside a couple of Paris exteriors – the crew says the work represented just about every facet of the visual effects process.

“Image Engine is traditionally known for its robots and creatures,” said Shawn Walsh, visual effects executive producer, “but, the opener was so much more involved, featuring detailed period environments, the carriage, digital humans, rain, clouds, water and a myriad of magical effects – it’s a real ‘kitchen sink’ of a sequence!”

However, the client knew the VFX studio’s creature capabilities and other experience would work well for the sequence, and encouraged the team to take on so much more.

“When we got this,” says Culpitt, “we were all, like, ‘New York? 1920s? Rain? And the opening sequence!?’ With a reputation as a creature shop, we thought the client might only want us to concentrate on creatures, but they knew we were capable of a lot more. And we’d done a whole lot of amazing effects sims and environment effects on recent shows. They asked us to take it all on, and I’m so glad we did.”