Zero Dark Thirty Case Study

Case Study

Zero-Light Mission: Image Engine works under the cover of darkness to create invisible effects for Zero Dark Thirty.

Image Engine provided over 300 shots for Kathryn Bigelow’s critically acclaimed Zero Dark Thirty, a chronicle of the decade-long hunt for al-Qaeda terrorist leader Osama bin Laden, which has been nominated for a 2013 VES Award for ‘Outstanding Supporting Visual Effects in a Feature Motion Picture’.

The work involved digital environments, hard surface animation, compositing and FX. In addition to creating hero assets such as the computer generated Stealth Hawk helicopters, the crew also digitally augmented the bustling military encampments, which included extensive matte paintings as well as the addition of upwards of 400 digital soldiers, lots of ground vehicles, helicopters, planes and all the auxiliary dust that each of these would kick up in the dirty, dusty environments.

Chris Harvey was the Visual Effects Supervisor for the production. Harvey oversaw the design and implementation of all the visual effects shots, with Jeremy Hattingh handling on-set supervision on location in India and Jordan where Chris joined him for the raid sequence. The project took place over a tight schedule of four months – and Image Engine was the main visual effects vendor.

It was of critical importance to the filmmakers that the CG elements and general filmmaking conditions were as true to events as possible, to support the integrity of the movie – with all the details coming under rigorous scrutiny. The crew had to dig deep to find aesthetic solutions within these parameters, with very little creative license to change the nature of things to make them ‘work’.

“Seamless, nuanced, and rigorously authentic, Image Engine’s visual effects take ‘reality’ to a whole new level.”

– Kathryn Bigelow, Director, Zero Dark Thirty

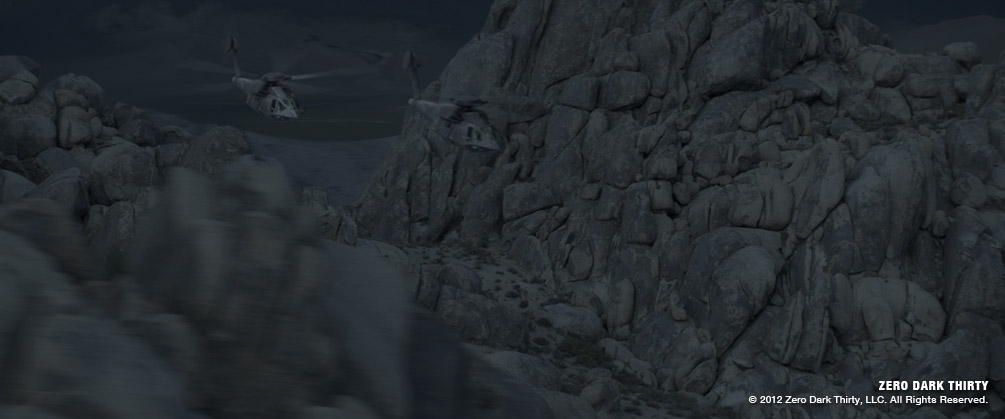

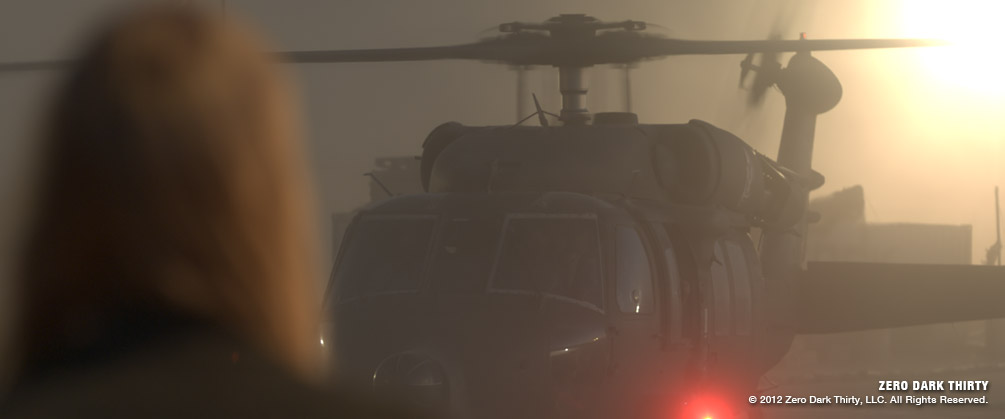

NO-LIGHT SHOOTING

The brief from Kathryn Bigelow for the night shoots presented one of the biggest challenges in this regard. In Bigelow’s words this was “not night shooting, but no-light shooting”. This no-light zone was an almost moonless night, so the Image Engine crew had to create a very subtle ambient light for their computer-generated assets.

“We referred to this internally as not being ‘sourcey’ – which means that the light is there, but never draws your eye as to where it might be from,” explained Harvey. “This zone had thinner margins than I have ever seen in terms of light. It was challenging of course, but the crew did a tremendous job of getting things to still be interesting, clear, and technically sound in such a narrow band of light.”

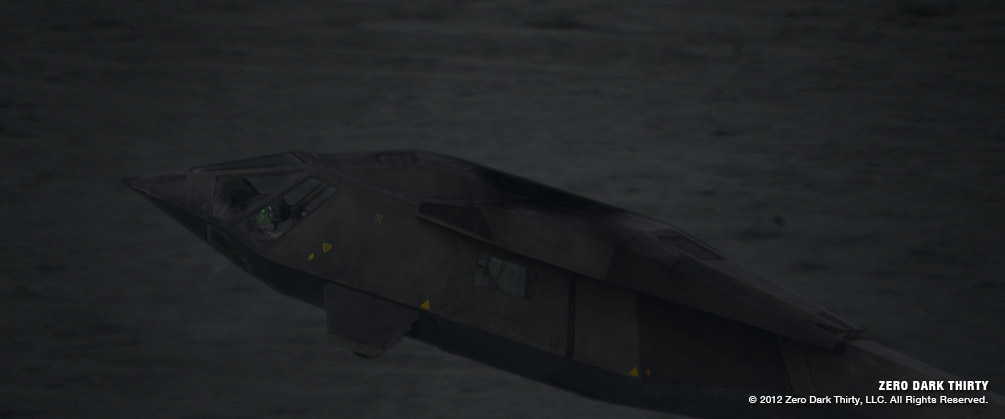

STEALTH HAWKS

The ‘Stealth Hawk’ helicopters were the most difficult assets to create under these conditions. “The helicopter had to stand out and shape nicely, but we kept all the diffuse and reflection values very low, with our highest value on the Helicopter generally below 0.05,” recalled Lighting Lead Mathias Lautour, who was also responsible for leading the Stealth Hawk look development.

“Having a fully black helicopter at night meant that the lighting had to be done mostly with reflections. This particular light component is delicate to tune and can quickly look very fake if the reflection shader/textures are not tuned properly, so we had to work hard to ‘sell’ the helicopter,” he added.

This top-secret military vehicle was designed to be unnoticeable in the real world. This design posed additional challenges to the crew – to make the CG version look realistic, with such limited material.

“Its shape consists of a few large flat polygons, with no complexity or color/material variations to make it stand out,” explained Latour. “But, complexity and color/material variations help make CG look believable, through how the lighting varies across the surface”. Therefore, a lot of attention had to be put into making these flat surfaces more nuanced during look development; no surface was created completely flat, no edge perfectly sharp, which generated just enough detail to appear believable on screen, while retaining its design integrity.

Production had two full-scale Stealth Hawks built. These were largely CNC milled, so the digital models were available to serve as the base of Image Engine’s model. To prepare for animation, Harvey chose to film real helicopters in order to get true and realistic performances out of the CG Stealth Hawks. “I have had to deal with digital helicopters before, and it can be shockingly difficult to get the motion right,” he said. “In this case, the process of filming real helicopters worked very well. It made for better composition, removed all guess work and ended up getting all the subtleties you get in a real helicopter.” There were a number of shots where the performance was completely changed, which were handed over to animation, who keyframed the motion, using the filmed footage for reference. For shots where the performance didn’t need to change, the Stealth Hawks were matchmoved with helicopters filmed on set (Black Hawks, and two other standard film camera helicopters).

“There were some nuances to how we handled this,” recalled Harvey. “In the case of the military Black Hawks, once they were tracked (provided Kathryn was happy with their performance) we were able to seamlessly replace them with the Stealth Hawks, and all that was left was matching the rotor RPM and flaps animation. When it came to matching the smaller helicopter’s performance the animators would have to scale and compress the curves to stop the Stealth Hawks from ending up looking like toys.” However, this technique did also mean a lot of painful paint-out for the compositors. “In some cases this included near full screen rotor blades moving against rocky cliffs!” he added.

DAY FOR NIGHT

The helicopter shots were also filmed at all different times of day and in different locations, which caused a good deal of disparity in terms of illumination. “Each of them needed a specific colour correction treatment so we couldn’t take advantage of the use of any sort of template to speed up the process,” recalled Jesus Lavin, Compositing Lead. “Some of them had a pretty hard keylight, while some others had a very diffuse one. Our goal was on the one hand to match the plates to the existing (VFX or non-VFX) night shots in the movie, and on the other hand, find a balance between all our colour-corrected plates. At the same time we would try to keep (or create, if there wasn’t any) some sort of light direction for the lighters to be able to play with. Sometimes the night grade would work right away, sometimes it would be a back and forth dialogue between comp and lighting.”

The lighting team took a creative approach to each individual shot to find the best lighting setup, so that the helicopter would look integrated, interesting and aesthetically pleasing. “The flat surfaces were tricky because they could flash or simply go black with a couple degrees difference in light angle,” said Harvey. “Lighters did not have the luxury of nice onset HDRIs because all of these shots were heavily re-graded to become night shots.”

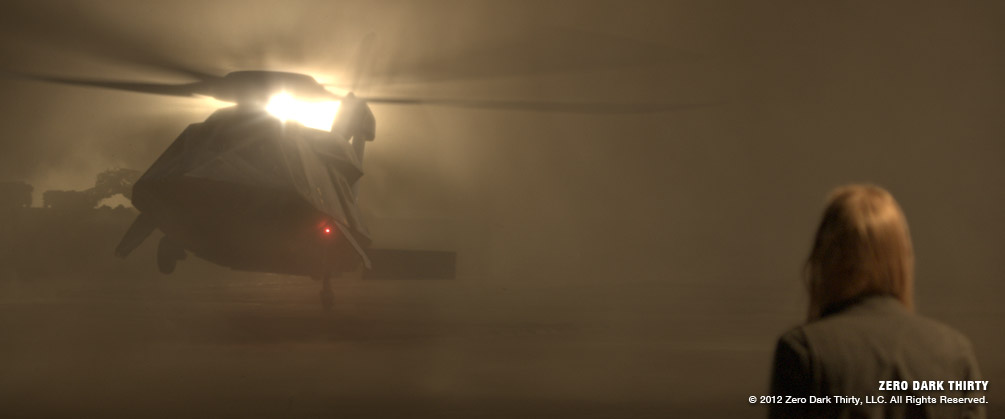

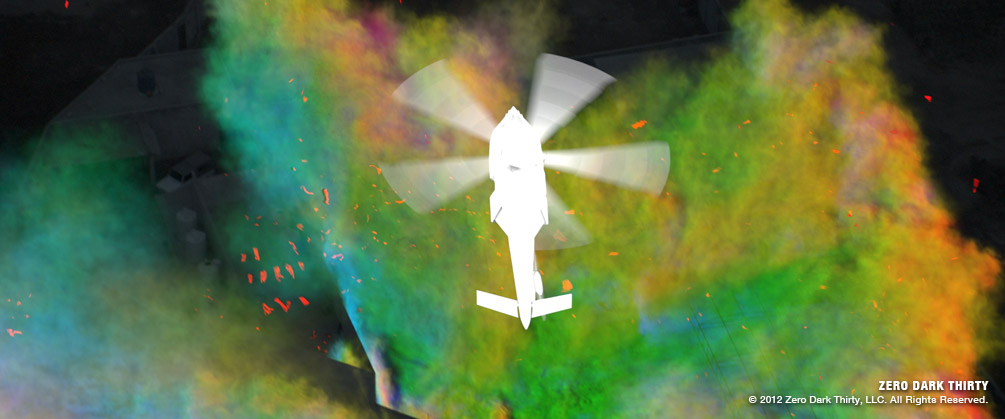

DUST FX

The team seamlessly integrated the CG helicopters into their environment with complex dust simulations. Real Choppers were shot on set to get practical elements, but it required further augmentation to sit the digital helicopters into those interactive environments, in some cases completely replacing what was in camera. “FX played an integral role in these helicopter shots. Not only in the obvious crash sequence but throughout all of them,” said Harvey. “Pretty much every Helicopter shot also had an accompanying heat distortion pass.”

Added to that was all of the other debris the team added into the dust clouds, which included bottles, plastic bags, paper bags, cardboard pieces, clothing and more, which all had to behave differently.

“For the debris we had a lot of variation in the types of objects that were getting thrown around the compound,” explained Sam Hancock, FX TD. “We developed a tool that enabled us to adjust the material properties of each object separately and simulate them all together. We used Houdini’s cloth solver for the deforming objects and the bullet solver for the rigid objects such as bottles and cans. These two solvers were used in the same simulation so that the rigid and soft objects could interact with each other. The dust simulation was used to drive the motion of the debris using a SOP Solver that we developed to apply forces from the dust simulation.” These seemingly small details were heavily art directed, and made a tremendous difference to the overall sense of realism – and were even integrated into explosion debris.

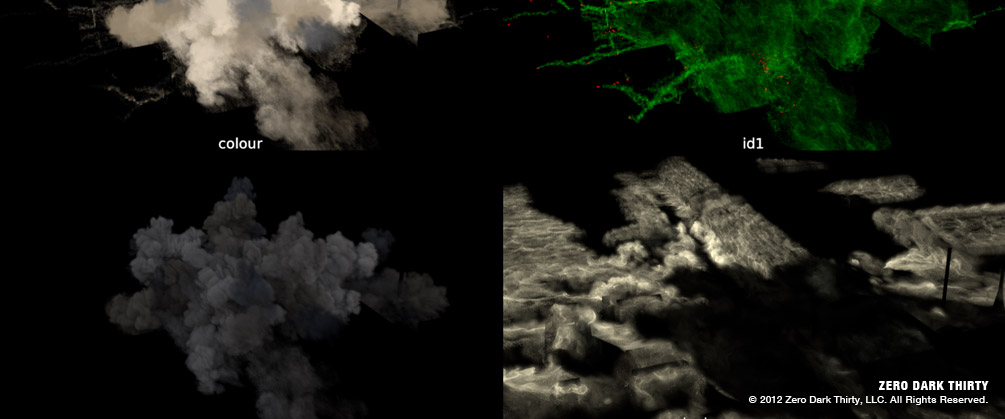

EXPLOSIVE FX

Two of the most highly charged sequences were the bombing of the Chapman camp and the helicopter crash. The Chapman bombing sequence was originally filmed with an impressive practical explosion, which Image Engine stitched together from various passes (covering the explosion, the car, people’s reactions with air cannons) filmed over several days. “This approach worked great for the low angle shot, however for the high angle shot Kathryn decided she wanted something even bigger… something really devastating,” noted Harvey. “This meant that everything after the first couple of frames had to be created digitally”.

“The explosions were mostly achieved using Houdini’s built in Pyro tools, and there were a few key additions,” explained Hancock. “We developed a method to introduce variation in the colour of the dust, this fit in nicely with the Pyro simulation tools and shader thanks to Houdini’s flexibility. The new support for rendering volumes with physically based rendering allowed us to render an ambient occlusion pre-pass of the dust which gave it a lot more shape in the final render. For the turbulence in the dust simulation we extended the tools already available in Houdini to adjust to the speed of the dust so that the turbulence controls were much more intuitive.” As well as countless simulations from the FX team for the actual explosion, the shot also included shockwaves, damage to surrounding vehicles and reactions from the digital soldiers around the set, who responded relative to their proximity to the explosion.

The helicopter crash took place during the concluding raid on the compound, and was subsequently destroyed in a spectacular explosion. “The whole crash sequence was pretty complex since it involved basically every single department in the project,” noted Lavin. Due to a late shot re-design, the original plates, which had been filmed for the VFX sequence, were no longer suitable. This required a lot of work from the crew to adapt existing back-plates for the new sequence.

Lavin continued: “From the comp point of view, we needed to clean our plates removing not just the helicopters that were in the raw plates, but also all the people and traffic in the streets of the village. Then we had to grade the shots, comp the lighting passes and integrate the FX.”

DIGITAL ENVIRONMENTS

The environments themselves were handled with extensive matte paintings, and involved a large team over two months to create armies of digital soldiers, the ground vehicles, helicopters, planes and atmospheric dust. These ambitious environments recreated the feel of bustling military encampments, literally springing to life at key moments.

Much of the aerial footage was shot handheld from a helicopter, which needed a tremendous amount of stabilization. In some cases this essentially called for a complete rebuild of the plate from the ground up in comp. The aerial shots also proved challenging for the matchmove crew who handled the instability with good old-fashioned 2D tracking; they also had several other technical hurdles to manage including tracking shots filmed through a night-vision filter, which produced a lot of atmospheric artefacts, and being given limited lens information or grids, a common problem with aerial footage. “Luckily 3DEqualizer has such powerful lens distortion solving tools that we were able to dewarp the plates enough to get a good solve,” said Lee Alexander, Matchmove Lead. “There were a handful of aerial shots that just wouldn’t solve correctly and needed a lot of hand keying in Maya to make work… luckily there were only a few!”

From the almost impossible ‘no light’ scenario through to the detail‐intensive dusty desert environment, the factual integrity of the movie gave the crew some incredibly tough challenges.

“During the project one of the mantras we would repeat endlessly was that we had to ‘feel’ things but not ‘see’ them,” added Lavin. “In the end, I think that is what makes this project stand out – being able to create shots with a quality that it is almost impossible for the viewer to quantify.”

“In visual effects you’re always striving for seamless photorealism – but this film really required the crew to push that concept to its limits, and I think the results speak for themselves,” said Visual Effects Executive Producer, Steve Garrad. “The reward for us was that by the end of the show Image Engine had delivered over 300 shots, which all worked very hard to ‘invisibly’ enhance the authenticity of the story.”

Thanks to the entire Image Engine crew. Special Thanks also to Kathryn Bigelow, Mark Boal, Colin Wilson, Megan Ellison and to all our friends at Annapurna Pictures & Columbia Pictures.