White House Down Case Study

Case Study

From creating photo-real environments to directing a digital cast of thousands: Image Engine helped digitally destroy one of the world’s most iconic buildings in key sequences of Roland Emmerich’s White House Down.

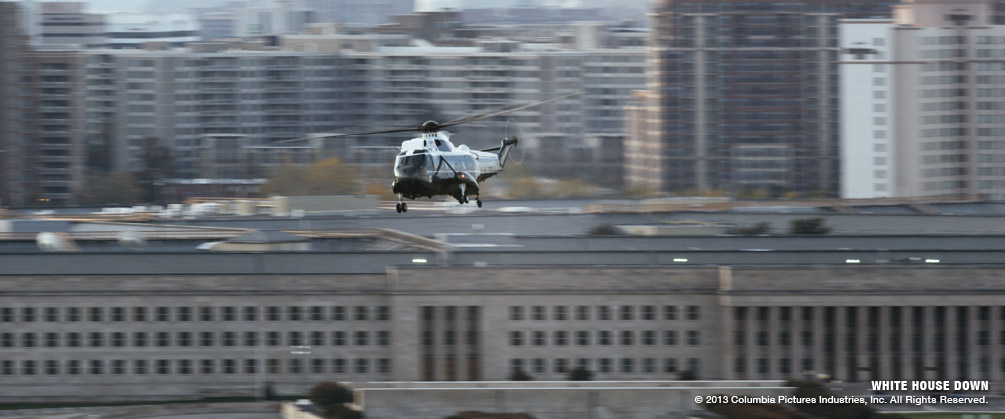

In late 2012, Mark Weigert from Uncharted Territory contacted Image Engine to talk about contributing visual effects for White House Down. Marc had recently seen Zero Dark Thirty and called Visual Effects Executive Producer Shawn Walsh to discuss that film and Image Engine’s work on it since there was a lot of computer-generated helicopter work to do for White House Down.

“Image Engine had previously had a great experience working with Volker Engel and Mark Weigert on a large creative previs sequence for the film 2012,” recalls Walsh. “So when the call came in, the company wasted no time in getting up and running. Ultimately, all of the preliminary discussions with Marc and Volker laid the groundwork for Image Engine’s involvement in White House Down because there was a mutual understanding of the kinds of visual effects methodologies that a vendor has to employ to achieve this level of complexity in full digital shots.”

Image Engine supplied 95 shots in total. This included two key sequences for the movie: the ‘Takeover’ of the White House and the ‘Aftermath’. Both incorporated the White House, in its pristine and subsequently destroyed state, the surrounding environments, hard surface animation of helicopters and a digital cast of thousands.

In the ‘takeover’ sequence, the establishing shot flies over the Washington Monument and reveals the White House. Two terrorists occupy the roof of the building, while military vehicles and crowds are starting to assemble on the ground.

Of the 15 shots that make up the sequence, one was entirely computer generated. Image Engine worked with a model of the White House and several models of the grounds and trees supplied by Method Studios, as a basis.

“The models and assets we got from Method were just the base of what we created for the shots,” explains Visual Effects Supervisor, Martyn Culpitt. “We received 2 versions of the White House model, each one had to be imported, each texture had to be modified and tweaked to fit within our workflow and colour methods.” The core challenge was to make the digital white house look realistic, as Culpitt explains: “It has a very unique look, the shadowing and occlusion of light seemed to play very differently than any other building – It almost seemed to emit light. We needed to do a lot of shader work to make it feel real and to work with our renderer 3Delight.”

The surrounding trees also needed extensive manipulation. “In our biggest shot we had over 800 digital trees,” he adds. “These also needed to be integrated into our environments. We spent a lot of time adjusting our shaders for each tree and its individual leaves to interact with the light correctly. Later on, we had to use specific depth mattes and other shader-developed maps to help integrate them with the smoke, debris and matte painting work.”

After creating the fully CG environment for the takeover, Image Engine then had to destroy it piece by piece for the ‘Aftermath’ sequence, creating crumbling facades, engulfing the top floor in flames, and generating plumes of smoke. The destruction extends out into the surrounding environment with burning vehicles and debris scattered across the site.

This sequence incorporated two fully computer-generated shots. The CG environment was augmented with matte paintings, adding lots of photographic details including broken windows, roof destruction, dirt and soot from the fires and smoke damage. The west wing and pool house also received matte painting treatment to create similar destruction. The White House grounds were painted to add tire track detail from the vehicles and debris from the explosions and crashed helicopters.

FX also played an instrumental role in creating the smoke. Multiple smoke simulations were created based on real life forces such as wind, smoke speed, emission rates, and collision with CG objects such as window frames. “The smoke had to roll out of the windows and up over the portico,” recalls Culpitt. “Once the sims were run they had to be tweaked to get the right feeling. This took a lot of time to get just right. In our biggest shot we had over 10 different smoke sims. The White House was on fire, the Black Hawks and tank were also on fire; they all needed individual smoke elements. Each smoke layer had many AOV passes to be able to grade and comp them properly. We also created individual smoke sims for the specific heat distortion for our helicopters.”

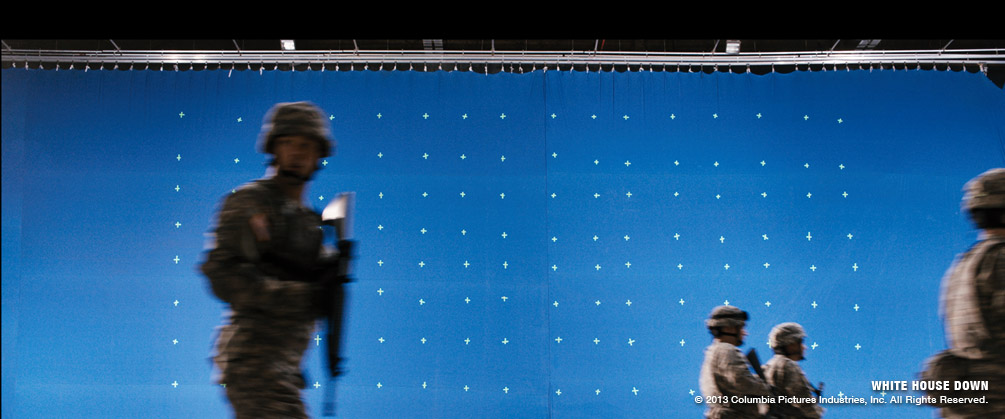

During the sequence a cast of around 10,000 digital characters was integrated into the action. “Image Engine initially received the base character assets from Prime focus but there was a lot of work involved in getting them to work within the Image Engine pipeline,” explains Lead Animator, Earl Fast. “The assets department created a cast of ‘Character Types’ (generic male, generic female, police, national guard etc) and created a complex ‘body part’ swapping system and defined body makeups within each character type category. On the rigging side each character type category then received its own skeleton and proprietary rig, giving the animators a great amount of control over the animations.”

A proprietary layout system created by Image Engine was adapted to generate and animate the crowds. “Until now this had only been used for small handfuls of people or larger but basic crowds seen in very, very wide shots,” says Visual Effects Producer Cabral Rock. “We evolved it to the point of being able to execute the crowd work required on WHD. We pulled off a crowd of thousands on the White House lawn, often seen quite close to camera, able to perform very specific actions depending on the needs of the scene. This was quite an achievement that was accomplished while in production, with very little R&D time in advance.”

“Using our system the animators were able to randomly assign each character’s properties and behaviour to achieve natural variety, while also clustering into animated groups, such as troops of soldiers, civilians and media crews,” adds Culpitt. “This way we are able to adjust and manipulate individual groups or people without having to affect the rest of the crowd.”

Image Engine created a complete DC city environment. This was used in both the “Takeover” and the “Aftermath” sequences. “The Washington DC environment was one of the hardest jobs for our Matte Painting team due to the level of detail involved. We had to make sure the quality of the city buildings would hold up to how close we got and for the many different cameras angles we had.”

The work ranged from creating simple structures with applied textures through to creating highly detailed CG models onto which sections of matte paintings were projected. The compositors added lots of other little details such as window reflections, light direction, shadows, sun glints, steam from vents, depth haze and flashing police lights to give the environment the movement and life of a real city.

“Overall, this project was a great example of how far Image Engine’s environment work has advanced in recent years”, says Walsh. “The team pulled out all the stops to assemble several very complicated, all-digital shots in a relatively short timeframe and achieved some great results. This work was happening alongside several other high-end environments projects at the company at the same time – and the outcome of all that work is a very robust environment pipeline.

Thanks to Volker, Marc and Roland for a great project, and we’re looking forward to working with them again in the future.”