The Thing Case Study

Image Engine has provided over 500 visual effects shots for The Thing (2011), the prequel to John Carpenter’s classic 1982 film of the same name. The prequel tells the story of the occupants of the Norwegian camp, who make the first fatal discovery of the alien space ship and creature, and ends where Carpenter’s film begins.

Jesper Kjolsrud helmed the project as the production Visual Effects Supervisor alongside Steve Garrad, Visual Effects Executive Producer. They worked closely with Director Matthijs Van Heijningen, Producers Mark Abraham and Eric Newman, Visual Effects Producer Petra Holtorf and Universal Pictures to realize a new vision for the 2011 film.

Image Engine’s contribution spanned over a year, from pre-planning, on-set supervision through to post-production with a crew of over 100. The majority of the work involved creating computer generated creature transformations and digital environments. In all, there were 167 100% computer generated creature shots.

“I want to congratulate and praise all the artists at Image Engine for all the incredible work they have done on The Thing. As being the prequel to John Carpenters The Thing the bar was already extremely high and Image Engine pulled it off. Not only the end result but from the very early concept phase Image Engine gave me the freedom and the creative support which was so essential to make this film work. Thanks again and hopefully till the next movie.”

– Matthijs van Heijningen, Director

CREATURES

On set, Kjolsrud helped to co-ordinate the efforts of multiple departments, including special effects, creature effects, visual effects, stunt performers and the wardrobe team to get the best photography possible in order to prepare for the digital builds.

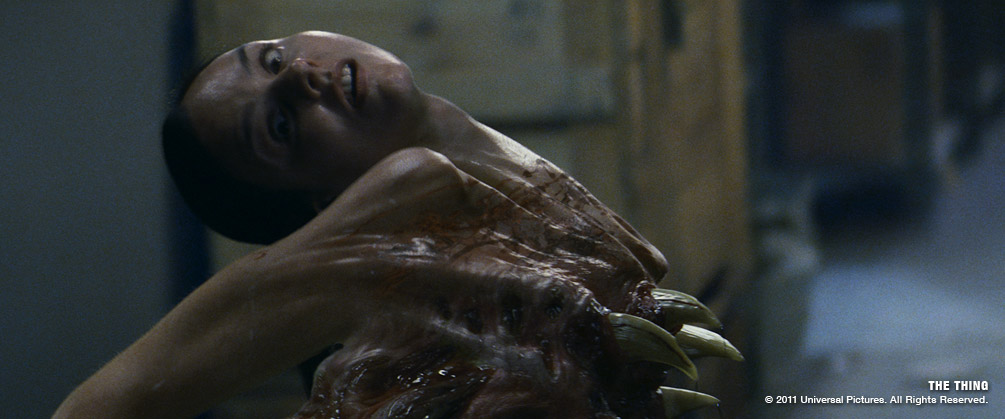

During production, it became clear that the overwhelming majority of the creatures would need to be entirely computer generated in order to perform successful mutations and react to ongoing design changes. Planning for the creatures in Postvis throughout the duration of postproduction, the team worked closely with the director and editors to establish the look of shots created entirely in CG.

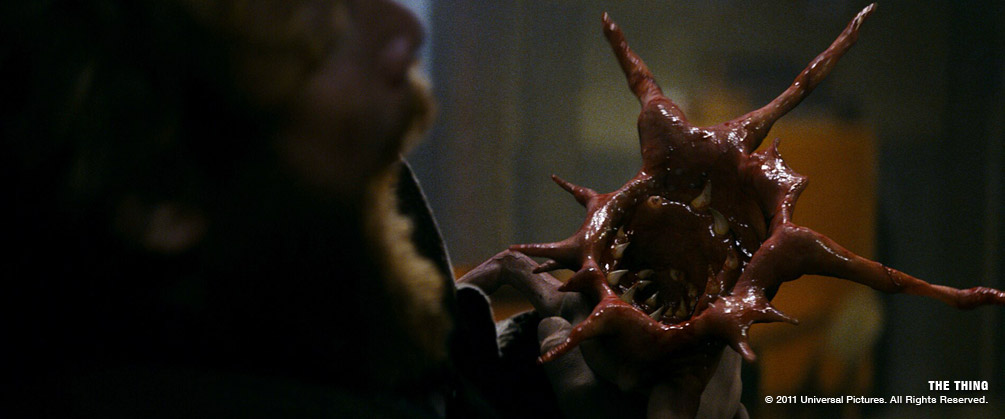

The creature transformations were overseen in post-production by Digital Effects Supervisor Neil Eskuri and Animation supervisor Lyndon Barrois. There were six hero transformations in all, each mutating in entirely different ways, and requiring different creative and technical approaches. “The creature’s monstrous form could be made up of any anatomy it’s ever encountered before” said Kjolsrud. “We had to think beyond the challenge of animating a creature rig and figure out how to go from A, which would be the human form – to Z, which would be the monster, and all the steps in-between.”

Because of the unconventional nature of their design, every creature in the film presented it’s own unique animation challenges. Ken Steel, Lead Animator explained: “For example the Edvard Arm creature that sprouts legs and runs off had 4 short legs on the right side of it’s body, 3 longer ones on its left side and a middle finger at the head that was meant to be used as a leg as well. While this made creating animation with realistic weight and balance a challenge, it also created an opportunity for us to explore how a creature like this might move in the real world and that, from an animation point of view is an ideal scenario.”

The unusual creature designs had complex rigs, some of which included several hundred joints.

Building on Image Engine’s proprietary asset management system, Jabuka, the rigging team developed a new modular system named ‘Riglets’. Fred Chapman led the development of the system, which had to meet strict requirements for efficiency of build and playback of the animation puppet as well as exacting quality of output.

“By developing Riglets we could standardize the build of each module, so that every arm or hand or spine built in a way that was consistent and stable without being constrained by how they connected to each other” explained Chapman. “We could attach a tentacle to a chest or a leg to a shoulder with a deformed hand on the other end. Riglets was invaluable in helping a small team to efficiently build and maintain the many creatures, digital doubles and props, during frequent design changes.”

Other efficiencies included handling organic deformations such as muscle movement and skin sliding through procedural calculations to give artists more control and a faster pipeline, adding in subtle dynamics only at the very end of the process.

Image Engine’s R&D team built the proprietary tools designed by the riggers including the spline IK system and multi-bone IK/FK joint system. They also developed a native skinning data format in Cortex (an open source library of tools for visual effects software development, led by Image Engine’s lead programmer, John Haddon), which gave faster and more controllable manipulation and transferring of skin weight data.

FX

The Thing represents the most challenging work to date for Image Engine’s FX department. The team, led by Greg Massie, decided early on to commit to using Houdini for the project and spent a lot of time integrating it into to the pipeline. In the end there was a 70/30 split of effects between Houdini and Maya.

The creature work was split in to two; general FX such as blood, slime, drool, flaps of skin and then the hero transformations.

“The general creature FX was something that we were fairly familiar with from District 9. We used a lot of nCloth for gore, nParticles for doing simple slime and Houdini wire sims for all of the creatures’ hair,” explained Massie. “The transformations, however, were a big leap for us. Most of them were full frame and integrating with human characters shot in the plate.”

Two of the most challenging were the Edvard/Adam face merge and the Sanders alien at the end of the film. “Edvard/Adam went through a huge number of iterations as we learned Houdini and learned how to integrate it in the pipeline.” Massie said. “The director had some reference of a face being punched in slow motion that he wanted us to match to. This made using simulation very hard and in the end a large number of custom built deformers were used to push and pull the face around in very precise ways.”

The FX elements for the Sanders alien face rip were completed in around 6 weeks. First a previs was put together to get accurate timings and to work out where the cuts would be. The initial sim for the skin was created using Maya’s nCloth then the result sent back to Houdini to attach to the original mesh, build skin thickness and to do tech fixes ready for rendering. The blood elements were then completed using the FLIP solver in Houdini. According to Massie, this is where the decision to invest in Houdini began to pay off: “It was a testament to Houdini’s rapid prototyping that allowed this shot to be completed so fast.”

COMPOSITING

For the compositors, the mutations also represented significant creative challenges and the deployment of several different techniques. For example, one of the most complex shots was the Edvard Adam transformation, which involves a facial merge between the live action plate of Adam, the CG Edvard head and projections onto a deformed mesh. The shot went through several design iterations, overseen by lead compositor Evelyne Leblond: “Because it’s a human face it had to be really perfect, so we wanted to keep as much of the original plates of Adam as possible” says Leblond. “It was necessary to break out every component and channel into comp, which resulted in hundreds of layers.”

Shots involving burning the creatures also involved the use of many different approaches to marry together practical, 3D and 2D elements. Kjolsrud had overseen the shooting of the plates, literally burning the puppets in order to establish the correct lighting on set and practical reference. However, once the CG creatures had been completed, the compositors had the task of translating the practical fire elements onto the new creature. “The FX guys made a base layer for fire and the compositors had to put in 2D fire to complete and enhance it. We literally used every technique we could think of to make this as seamless as possible.”

DIGITAL ENVIRONMENTS

Whilst the creatures were the stars of the show, the film also required extensive digital environment work. Many of the exterior shots required digital background extensions to be married to the foreground practical set that was filmed in Toronto. This work also required computer generated ice/snow for many of the foreground shots under the actor’s feet, as well as creating other CG assets and architectural elements including an 100% CG helicopter and Spryte.

“Two of the largest challenges were creating the ice cave with the spaceship and the environment within and around the Thule camp” according to Neil Eskuri, Digital Effects Supervisor. “Scale was always the issue. The spaceship was said to be 1000 feet in diameter, which meant the ice cave had to feel immense. The camp, a partial set created and shot in Toronto, had to be digitally extended and put into an environment which would make it feel small and vulnerable.”

The FX team was also heavily involved in this area, and covered everything from the collapsing ice cave through to snow, snow and more snow! This was primarily achieved using POP networks in Houdini for the snow and RBD simulations for the breaking ice. A lot of time was spent integrating the output of these sims with our rendering pipeline, which is hosted in Maya and rendered in 3delight.

“Overall, the project involved the whole gamut of visual effects work” said Kjolsrud. “Kudos to the whole team at Image Engine, who really stepped up to the plate to deliver above and beyond what was required to live up to the 1982 Carpenter version.”

“The Thing provided us with a great challenge and opportunity to showcase Image Engine’s capacity to create stunning creature animation.” said Visual Effects Executive Producer, Steve Garrad, “The advancements that were made to the company’s proprietary tools and workflows throughout the show will help us to continue to raise the bar on future projects.”

DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION 1.5Mb