Elysium Case Study

Case Study

From designing and creating the epic man-made space station to bringing the film’s photo-realistic droids and spacecraft to life, Image Engine has completed its most ambitious project to date for Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium.

During production on Neill Blomkamp’s debut feature film District 9, Image Engine started talks with the Director about an exciting new project, with a much larger scope of visual effects. This project would later become known as Elysium, his dystopian vision of the future, wherein the population is divided between the very wealthy, who live on a pristine man-made space station, and the rest who remain on Earth in a state of poverty and decline. Following the success of the collaboration on District 9, Image Engine soon re-teamed with Blomkamp to become the lead visual effects studio for Elysium overseeing the full scope of work required for the sci-fi epic.

Image Engine managed the multi-vendor show from a central hub at its facility in Vancouver BC, and took on the majority of visual effects work in-house. Image Engine’s Peter Muyzers (Academy Award® nominee for District 9) was the Visual Effects Supervisor for the production, working closely with Blomkamp to oversee all of the visual effects for the film, while Shawn Walsh took on the role of the film’s Visual Effects Producer, to manage the overall visual effects budget and vendor strategy.

Around 1000 visual effects shots were completed in total for the production. “We collaborated with several fantastic partners to take on specific areas of focus, which represents around 30% of the work,” said Walsh. “These included Whiskytree, The Embassy VFX, Moving Picture Company, Method Studios, 32TEN Studios, Animatrik Film Design and Industrial Light & Magic. Managing the multi-vendor project from a central hub at Image Engine allowed us to leverage the infrastructure we have in place at the facility, as well as call on our relationships with various colleagues in the industry to manage the visual effects efficiently.”

“We were thrilled when Neill brought us on board to manage the visual effects,” said Muyzers. “This was a big step up for the company. From the beginning we knew that Elysium would involve an extremely broad range of work because we were essentially creating a whole world from scratch – the scope and variety of work was bigger than anything we had ever done before.”

Designing a Perfect World

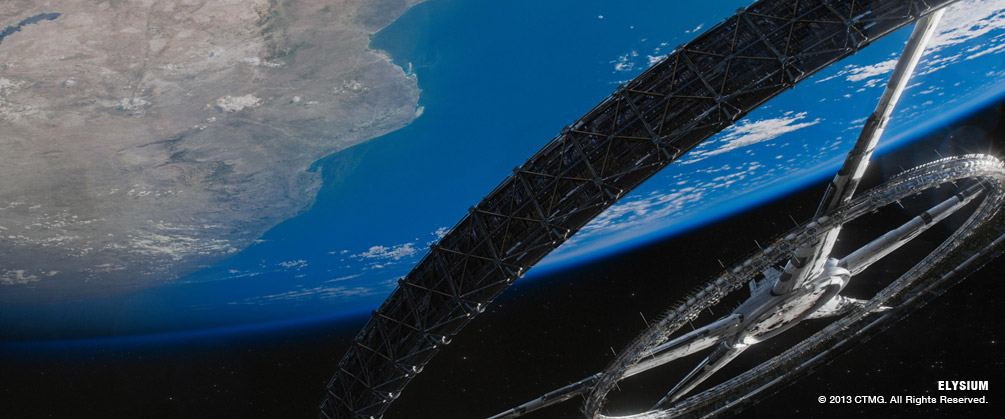

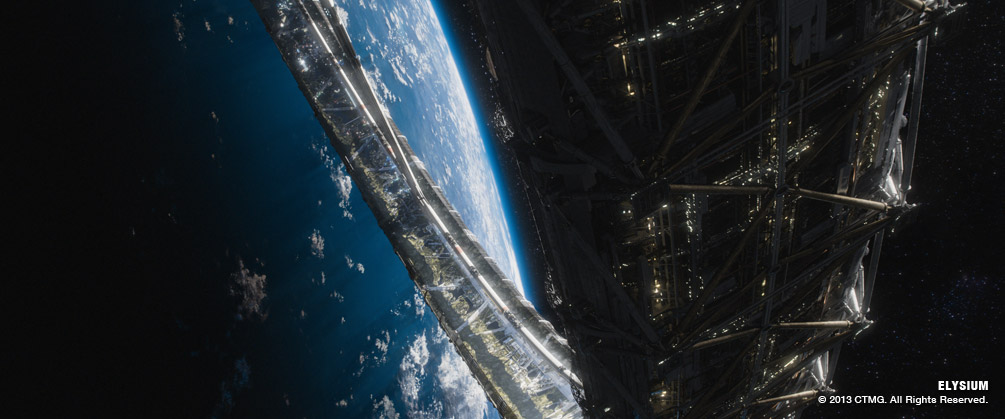

The biggest visual effects challenge by far was the torus of Elysium, the luxury orbital space station, which was inspired by drawings from concept artist Syd Mead.

Image Engine set up an in-house art department to fully realize the design, with Muyzers leading a team including Visual Effects Art Director Kent Matheson and Concept Artists Ravi Bansal, Mitchell Stuart and Ron Turner. “We started out figuring out the physical aspects of the thing, such as what made it mechanically possible: how it was held together, reinforced and supported, to how it would be inhabited and populated, and what kept it functioning,” explained Kent Matheson. “There were designs for internal factories and external support structures, hangar bays, buildings, and for the topography and city plans of the Ring surface.”

The design had to take into consideration the scientific research that underpinned the concept of the torus, alongside the artistic and narrative challenges of creating a believable world for the story to take place in. “It was important to Neill that Elysium was a completely believable environment, so we also looked at present day technology and engineering to keep our designs grounded in reality,” said Muyzers. “To maintain the elegance of design but with a robust ‘believable’ construction system, all of our concepts were accompanied with real-world NASA images and mega-construction reference from projects around the world,” added Mitchell Stuart. “This included refineries, space shuttle gantries, giant cranes, aircraft carriers, aircraft hangars etc.”

Elysium’s design included a discretely exposed underbelly of mega scaffolding, similar to oilrigs or refineries, contrasting with its slick exterior paneling. “Because it had to be believably built by us in the not too distant future, most exterior panels were meant to be transportable from earth – so nothing too big,” continued Stuart.

The team spent many months conceiving of each individual piece of engineering for the structure inside and out, from the hub, spokes, struts and linkages through to the exterior structure & inner ring. The design of the terrain took reference from mansion-studded aerial views of Malibu and Bel Air and the architectural design on the surface, was inspired in part by the fluid designs of Zaha Hadid and Calatrava architecture.

“During the design process at Image Engine, we figured out all the aspects of what life on Elysium should look like – working closely with Neill on establishing a set of reference images and gave that as a template to all the crew who would subsequently work on the environments, so they would know exactly what to execute,” said Muyzers. “Neill had specific requirements of how far the mansions should be spaced apart, how many trees & water bodies, the municipality areas and so on – so we were able to give all the artists really good reference and feedback.”

The design then moved into postproduction, where the entire ring was digitally generated from scratch.

“The environments on Elysium were a two part story,” recalled Muyzers. “After we had nailed the designs we had to embark on the challenge of executing that work. It was quite an enormous task – the complexity of the ring, the detail that was required to make it look very real.” In fact, the geometry of the Elysium environment was so complex it contained upwards of 3 trillion polygons and took over a year of postproduction to create.

The all-CG creation of the Ring and terrain was split between Image Engine and Whiskytree in San Rafael. The two companies collaborated to create a cohesive environment – Image Engine took on the hard surface structure of Elysium while Whiskytree handled the terrain surface. “We developed a unique situation, where Whiskytree almost became an extension of the Image Engine environment team; sharing assets and renders so that the results are really seamless,” recalled Walsh.

Meanwhile, Back on Earth…

The environments of Earth in 2154 were envisioned in an entirely different way. The Image Engine design team was tasked with imagining the ruined city of Los Angeles in a future marked by overpopulation and poverty.

Research into future city planning for the future Los Angeles gave the design team some realistic perimeters to work within, which could then be broken down to achieve their interpretation of a ruined city. “The challenge of designing the views of future Los Angeles was to imagine the current city core in the manner of an overgrown favela but still keep it real,” explained Matheson. “We ended up with the idea of an LA core of towers that was essentially an aerial city state unto itself, lived in and maintained by people who practically never left, creating this maze of bridges and extensions and levels.”

Industrial Light & Magic expertly crafted the LA city sequence.

VFX Shoots & Space Vehicles

Muyzers oversaw the filming of plates for the visual effects shots on set in Mexico, Canada and California, and Image Engine’s Associate Visual Effects Supervisor Andrew Chapman supervised the 2nd Unit plate and pyro-photography. “For the more advanced visual effects shoots we were actually working in a harsh environment – including the world’s second largest dump outside of Mexico City”, recalled Muyzers. This created quite a few challenges for the filmmaking team, however the practical elements that came out of the dirty environment helped add a gritty sense of realism to the visual effects.

“Neill likes to keep the majority of his plates intact,” described Muyzers. “That’s part of his shooting style – he gets as much in-camera as he can. So, early on we discussed how we could integrate the sci-fi flying vehicles such as the ‘Raven’ and the immigrant shuttles into these plates by using real helicopters. This was done to provide genuine interaction with the environment, as the blades of the helicopter would kick up a lot of dust. It was really also a clever way to ensure that the camera crew had vehicles to frame – everyone knew where the vehicle was at any given time. We had to insert the VFX behind all of the real debris on screen so there was a lot of paint out, roto work and so on, to integrate that,” added Muyzers. “But this process allowed for a more real picture in the end.”

Senior Compositor, Janeen Elliott agreed: “I find that incorporating CG elements into a “dirty” live action scene is typically easier to make into a successful comp than a clean fully CG shot. The biggest challenge that the extra dust on set created for us in comp was in the plate cleanup – removing the original helicopter was definitely tricky at times. But barring that, the dust added a level of realism, not to mention how the helicopters proved to be lighting reference for the lighters. In an effort to get the ship to blend into the plate, it was a matter of finding dust elements that were similar to what was in the plate, or that you would think the ship created. If we didn’t find an appropriate live action dust element, then the task went to our FX crew to help us out.”

Lead FX artist Koen Vroeijenstijn created FX rigs for heat haze, smoke, engine thrusters, and ground dust work. A team of 5 artists was tasked with adding all of the engine effects to all the vehicles both on Earth and on Elysium. Also, additional debris was added using nCloth in Maya; trash on Earth and leaves and other organic matter on Elysium.

“While rigging these ships, real life mechanisms were used as reference for maintaining realism in the small details of the shuttle designs,” said Tim Forbes, Character Rigger. “For example, many of the shuttles had complex landing gear systems that were developed through collaboration between modeling and rigging to meet the design requirements. The reference to real world examples of similar mechanisms helped us create effective functionality in their movement and believability of the load bearing structures. All shuttle animation rigs had automated landing gear retraction systems that would enable the animators to control a very complex motion off one attribute, with total control to offset or override any part of the landing gear.”

Chapman worked with 32Ten Studios who built large-scale pyro set-ups to match the spaceship explosions that Image Engine was creating in space. “Getting the zero gravity look in space added complexity to the shoot, so this was a combination of releasing pyro down and shooting up at it or vice versa to get things like fire and smoke to move in different directions to sculpt the elements that were needed.” recalled Chapman.

For the 100% computer generated space shots, determining a compatible shooting style in space was also a challenge, as Chapman explained: “It was important to emulate Neill’s style of shooting in our digital camera movements – so we had to develop a camera language that tied back in to the rest of the film. For this we turned to Animatrik Film Design to do a mocap shoot for the virtual camera work. We were then able to play back shots as though we were the camera operators, to frame up on spaceships as they went whizzing past – then when the mo-capped camera data was applied back to the cameras for final shots you’d get noise and bounce and imperfections of a real camera operator trying to follow the shot.”

Deceptively Digital Droids

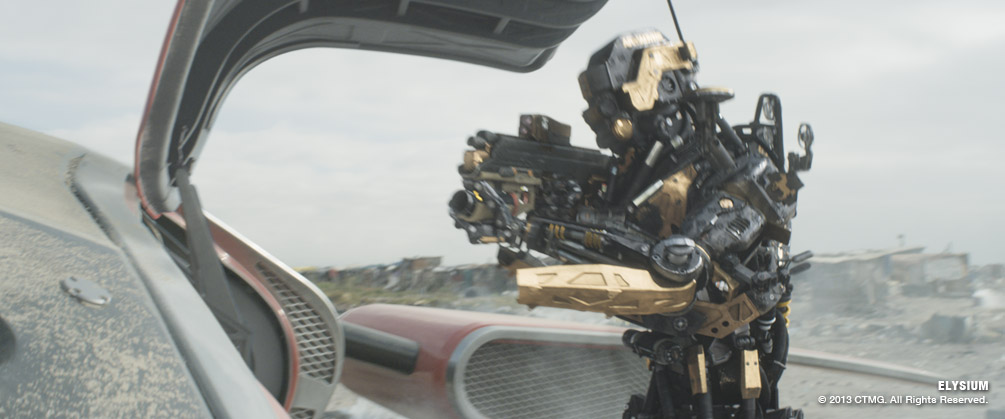

Having earned a reputation for creature animation on District 9, Image Engine took on creating the 100% computer generated droids, which were played by stunt performer in gray suits on set. These performances provided reference for the subsequent key-frame animation of the digital droids. The animators used a process called rotomation, where the animators use the match-move data to block in the motion of the performer making sure to replicate every movement as closely as possible.

“It was often through this process that a level of interpretation had to be worked into each performance,” explained Senior Animator Earl Fast. “The CG droids are rigid body machines that have limitations to some of their movements, rotation points, flexibility, and body mass distribution are all factors that the animation team had to take into consideration when animating the droid asset and they did not always match the corresponding attributes on the ‘organic’ actors. Machines have hinges and precise rotation points and many pose adjustments had to be made to visually match the actors performance as well as trying to cover as much of the actor as possible in an effort to reduce the amount of paint-out required to remove the actor from the original plate.”

The original droid designs came from Weta Workshop, and went through a further design refinement process at Image Engine in postproduction, which included the addition of tools and gadgets. “Concept artist Ravi Bansal added extra apparatus all over them, like little panels that pop out, and sensors and weapons,” recalled Chapman. “These were very practical tools for the droids, and gave a sense of them reacting to the situation around them. This was important to make them feel like characters in the scene without being able to portray emotions.”

The different types of droids ranged from scruffy earth-based security droids to factory-fresh droids on Elysium and luxuriously detailed private citizen’s droids. We did a lot of work in the look and texturing to make it clear how they had been used, and their purpose,” said Chapman.

“In texturing, we streamlined a process in order to quickly facilitate material and color changes on the fly for rapid turnaround,” explained Lead Texture Painter, Justin Holt. “We approached the paint work for the droids as if the paint was being fabricated in real life. We first painted the droids clean off the factory lines and then began the process of delicately adding on layers and layers of details, dirt, dust, scratches, chips, dents, oil smudges, sun damage, etc. until it matched the worlds and environments in which they were placed in the film.” As with all other elements in the film, all of the references for the engineering and texturing had to come from real-world reference, to add an extra layer of authenticity to their look and performance.

The realism of their performance was also determined by their seamless integration into their environment – which was artfully handled by the lighting and compositing crews.Lighting Lead Rob Bourgeault explained: “The lighting department would analyze each background plate and associated HDRI in order to determine the elements necessary to complete this goal.”“The material quality of the droid was highly reflective which was advantageous in having the asset more visibly interact with its environment,” he added. “Multiple reflection cards were used to enhance the droids interaction with close proximity elements.”

Once the lighting set up was in place, the real challenge was coming up with a way to automate the process. “It was key that multiple artists could inherit the sequence based lighting scene with minimal setup time and technical complications,” continued Bourgeault. “Senior Lighting TD, Edmond Engelbrecht created a script that would import and reference the required elements including camera, assets, lighting rig components, and render passes. This allowed lighting artists to build lighting scenes quickly for their shots and focus more on aesthetic aspects of lighting and render management.”

The droids were rigged using a custom-rigging system. In total, there were 686 controls

on the base droid model. This included fine detail offset controls for piston positions and tweak controls for cables to help animators match specific silhouettes and offset positions of the cables. “As in all our animation rigs any automation we provide for animators to increase their efficiency always come with an override to blend off the automated animation and an offset to augment or replace it as required,” explained Tim Forbes. “Our approach at Image Engine is to always put as much creative control as possible into the hands of animators to shape the look of characters on screen yet structure the controls in a way that is intuitive to interact and the sheer number of them is never overwhelming.”

Image Engine’s proprietary solution for blending parent spaces of control objects within an animation rig gives animators the flexibility to configure the rig precisely. “For the droids we extended this funtionality to add mocap parent spaces to allow animators to blend in and out of mocap animation, or to add offsets to the mocap animation,” adds Forbes. “We were therefore able to provide rigs that could ingest mocap animation with almost no additional overhead to our regular build or animation processes or to our pipeline.”

Blending Practical and Visual FX

“One of the shots that I’m most proud of is the exploding droid,” said Chapman. The shot was filmed using a gray-suit performer on wire-pull to emulate the physicality of the droid being blown backwards, with practical special effects placing chargers in the ground, and rigged in the air to generate the look of exploding rounds. “This was a great example of SFX and VFX working really well together,” he added. “Back at Image Engine, this was driven by Senior FX Artist, Greg Massie, who did an incredible job of putting together the myriad pieces to make it happen. This type of shot does not go through the normal pipeline of animation – lighting – FX – compositing – it was all those various things feeding in and out of each other in a very fluid way.”

The slow motion shot had to have an extremely high level of detail. The simulation was done as one continuous shot with 3 different cameras for the edit. “There were many iterations of animation to figure out at exactly what point the take over would occur and to make it work well with all three cameras,” explained Greg Massie. “FX was split in to 2 sections, the explosion of the bullets and the droid destruction. Simon Lewis handled the explosion cloud. One big challenge was the concussion effect during each progressive explosion. This was achieved using simple forces but getting the right look and feel took considerable tweaking.” The droid destruction was considered challenging because of the complexity of the droid and the number of pieces it needed to be shattered in to, as Massie explained: “Neill wanted it to be completely shredded but still to have recognizable components, for example, a shredded arm still needed to visible as it was destroyed.” He created this in Houdini and leveraged the procedural approach that Houdini is founded on. “Different numbers of bullets, size of shredded pieces, destruction timing, and deforming geometry could all be tested very quickly,” he continued. “Timing of which bit broke when was built in to give maximum flexibility. Due to the complexity of the model the rig was broken up to different body parts and run in parallel to maximize turn-around on iterations.” Additional elements were added such as particles at split points when geometry was destroyed, oil-like fluids, broken wires and sparks were all added in to the mix, most of which was cached in Image Engine’s Cortex-based format and passed on to the lighting department. Stephen James and Lionel Heath handled the compositing of the shot. “A lot of work went in to creating the lens-like effect that radiates out from the concussion. This added force to the explosion as it warps the air around it,” added Massie.

Tools and Workflow

Rendering for Elysium was split between 3Delight and Arnold, with the latter used for shots shared with Whiskytree. Image Engine’s R&D team improved upon their Cortex driven Look Development and Lighting system, which was used for the 3Delight rendering of droids, vehicles, digital doubles, and crowds. R&D developers David Minor and Luke Goddard were also heavily involved integrating Arnold into Image Engine’s pipeline, for rendering the hard surface structure of Elysium. Luke Goddard generated a new solution to handling ray-traced noise caused by the high level of glossy details within the colossal habitat of Elysium. This drastically reduced render times by expanding the use of a temporal filter to attenuate the weighting of a non-local means algorithm, which selectively refined its result.

The modeling pipeline at Image Engine is Maya-based, with texture painting all handled in Mari. Image Engine’s animation pipeline uses Maya as a platform, making heavy use of proprietary deformers, all managed by Riglets, a modular rigging system created by R&D developer Andrew Kaufman and Rigging Supervisor Fred Chapman.

All the compositing was handled in Nuke, which was also complemented by proprietary tools from the R&D team, like the temporal denoiser described above. Compositing development was also supplemented by TDs and leads, who built show or sequence specific tools. “Jordan Benwick, Compositing Lead, created a particularly cool gizmo which standardized the mechanical lights throughout the show,” said Elliott.

“It followed the color of the lights, created a star filter and glow, and lens flares that were random enough to feel as though it wasn’t generic, but consistent enough to feel like it was shot for the same show. This was used with minor tweaks for everything from ships to droids, to the lights in the Gantry fight sequence.”

The workflow between all these departments is made possible by Image Engine’s proprietary Asset Management system, Jabuka, which went through a complete redesign to handle the massive scope of work involved in Elysium. R&D Lead Lucio Moser, and developers Ivan Imanishi and Paulo Nogueira, pioneered the new approach towards Asset Management, leveraging Image Engine’s open source initiatives, Cortex and Gaffer, to lay the groundwork for the connectable node graph system and cross application UI, which is used by all artists in Maya, Houdini, and Nuke.

The production’s color workflow system used the Academy Color Encoding System (ACES). “We established an ACES workflow between IE and Vancouver-based digital intermediate facility Digital Film Central,” explained Muyzers. “Once that was established we could quite easily share various LUTS and set ups between the other studios.”

The film was shot on the red epic camera with anamorphic lenses, which captured a maximum of 3,300 pixels of resolution. To support this, the visual effects were created at 3.3K resolution for final film output at 4K. Muyzers and Blomkamp were able to review all the film’s visual effects at the highest possible resolution at Image Engine’s purpose-built 4K screening theatre, which was the first of its kind in Vancouver.

Shotgun was used to help manage the production across all the vendors. “We’ve been using it internally for some time, but found that it really delivered efficiency in managing reviews and notes across facilities,” added Shawn Walsh.

Much of the postproduction took place in Vancouver, BC. “What was exceptional about what Post Production Supervisor Brad Goodman was able to assemble with the help of Victoria Burkhart, Associate Producer, was the proximity of being able to locate Neill, Editorial, Sound, and DI, and several of the Vancouver-based VFX facilities including The Embassy VFX, Method Vancouver and MPC Vancouver, all within walking distance of Image Engine,” recalled Walsh. “In this day and age you normally tend to have a lot of virtual communication, but we sort of bucked the trend, and tried to keep people in face-to-face contact on very frequent basis. We had Neill in studio really frequently throughout post – we saw him in regular intervals and that really helped us seek approval, make corrections and work progressively and effectively throughout the entire run of postproduction. These kind of efforts that were put together to try to support the film were absolutely crucial to the end result.”

For many of the team, it was the Director’s clarity of vision that helped overcome the VFX hurdles on the show. “Neill has a way of working that is very specific and focused and his vision is always very clear to those that are working directly with him,” said Walsh. “This creates a kind of economy in the way that we execute visual effects that I feel ultimately contributes to the level of quality and execution of that work. What excited me most when we first started working on Elysium was the opportunity to collaborate with Neill again, and to ultimately push the work of the studio to the next level.”

“When I look back on Elysium I’m really proud of the variety of work we did on the show,” recalled Muyzers. “I think that after District 9, a lot of people were wondering where Image Engine would go next and I think that Elysium has definitely shown our capabilities in terms of handling the wide scope and volume of work.”

For Muyzers, collaborating with Blomkamp for the second time helped get the work done more efficiently. “The visual shorthand that we have learnt over the years has been invaluable and I think it really helped us manage the many creative challenges of this project,” he added. “Neill is a truly visionary director, and I think that everyone who contributed to the visual effects should feel proud to have helped turn that vision into a reality. My sincere thanks to the hardworking crew at Image Engine and to all our partners for their amazing hard work.”