Chappie Case Study

Case Study

Image Engine reveals how a dedicated visual effects team brings the illusion of life, character and emotion to an otherwise expressionless police automaton.

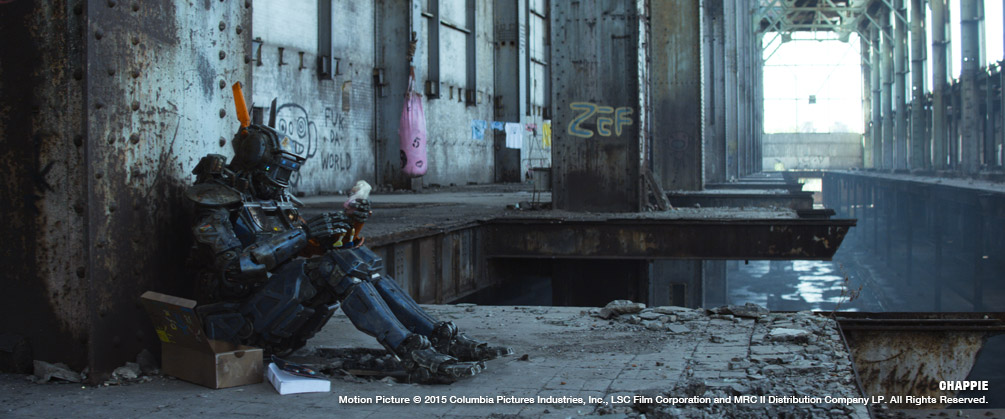

In Neill Blomkamp’s Chappie, Image Engine didn’t just need to bring an expressionless police robot to life – they needed to make the audience care for him as if he were another human character. That’s no mean feat. But, thanks to the committed efforts of the team, the ‘Streetwise Professor’, as Chappie came to be known, wowed everyone who followed him on his journey.

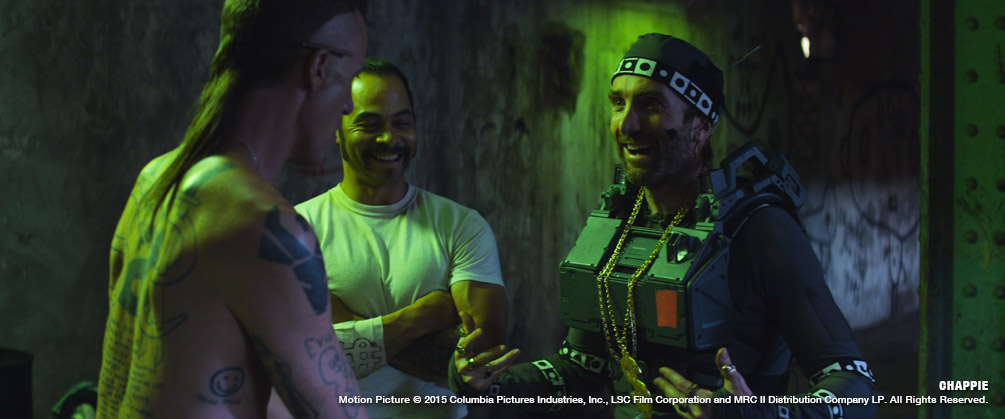

Taking place in a near-future police state watched over by automatons, Chappie sees one such robot – the titular Chappie, played by Sharlto Copley – stolen and reprogrammed to think and feel. In Blomkamp’s trademark style, Chappie tackles issues of corruption, oppression, and what it really means to be ‘alive’.

Image Engine was brought on board following its work on Blomkamp’s previous projects District 9 and Elysium. In fact, the origin story of Chappie at Image Engine included completing a fully fledged short film for Blomkamp featuring a early development version of the robot in some 30 shots. This film, completed during hiatus on Elysium was key to assisting the filmmaker in retaining creative control and manufacturing a compelling context for what was to become Chappie.

“That test work was a huge creative and technical ‘heads up’ for us” says visual effects executive producer Shawn Walsh. “Neill has been such an amazing collaborator – and we knew then that he’d given us our biggest challenge ever. To have an entirely digital character carry his film. The team responded fabulously, caring deeply and wanting to support Neill 110%.”

Around 200 visual effects artists and production staff were behind the complete creation of the entirely digital robotic protagonist and a number of other machine creations. Ultimately handling over 1,000 shots – and close to 70 minutes of screen time for Chappie – it was one of the studio’s largest projects to date.

“I would say that this show really reaffirmed just how important having a plan up front is,” says Chris Harvey, visual effects supervisor on Chappie. “That’s an obvious statement to make, but you might be surprised how often it’s not the case in film production. Spending and investing that real hard time up front will always make things smoother later down the pipeline, and what we achieved on Chappie is certainly a display of that.

“I’d like to echo something I believe Phil Tippett once said: we need to stop always looking for ‘what’s wrong with a shot’, and shift our focus to looking for ‘how to make it better’. There is a difference, and you can see that difference throughout Chappie.”

Getting Physical

In the past, working with Blomkamp, Image Engine collaborator Weta Workshop was responsible for many of the concept designs that went into the physical, practical models used on-set, which would then be used as reference for Image Engine’s 3D model makers. Not the case with Chappie. For this production, things were somewhat reversed: Image Engine worked with Weta to produce final 3D concepts of the robots and vehicles, which were then used as templates for 3D printing and constructing the live action props.

Getting the physical design just right was core to Chappie’s success, as Blomkamp and Image Engine wanted to make on-screen robots that would move and act in a realistic fashion, with no quick fixes or ‘cheats’ like ball joints used.

“There was no one single thing that was going to make him work, and it wasn’t just about making something computer generated fit into the live action plate,” explains Harvey. “Sure, he had to look real, but the real trick was getting past that and to the place where the audience would hopefully totally forget about him as a digital effect and cross over to a place where they bought into his character, his emotion and get caught up in what he was feeling. That was the trick we were pursuing.”

Barry Poon, digital asset supervisor on Chappie, found working in this somewhat-reversed fashion a refreshing change: “One of the really great things about working on Chappie was getting the opportunity to work with Weta Workshop and Neill [Blomkamp] on the Chappie and Moose designs,” he says. “Seeing the characters in 3D before they were built allowed us to work out some of their design and movement limitations. It also gave Neill a chance to make some changes before he started shooting the film.

“Chris Harvey, and on-set visual effects data coordinator Neil Impey photographed an enormous amount of texture and look development reference of Chappie and Moose, under multiple lighting conditions,” continues Poon. “That reference was used by our lead texture artist Justin Holt and lead look development artist Mathias Lautour, along with their teams, to create the textures and look dev for the two hero characters.”

What’s the Damage?

It wasn’t just a case of crafting a single Chappie model and being done with it – Image Engine had to create 16 different damage states for the robot, accomplished through texture, model and look development variations, or a combination of the three. Asset builds were managed with Shotgun and Maya communicating directly, along with a proprietary asset management workflow developed in-house to make sure everything went as smoothly as possible.

Shotgun was utilised across the production, but one particular application that stands out is how it was used to monitor Chappie’s battery level display from shot to shot, ensuring it read correctly and that any damage taken remained consistent. When an artist loaded a scene, the software would read from Shotgun and know which Chappie damage state had to be loaded. And as some of the damaged versions of Chappie were straightforward texture-swaps, Shotgun was able to handle them automatically. This combination of technical knowhow and pre-built tools meant the management of assets was smooth and painless, even with a great deal of data to sort through.

Justin Holt, lead texture artist, explains how the damage states tied in with his painting: “This required a considerable amount of planning and organization before I even started, because the only way for me to paint Chappie properly for all of the damage states and hit my deadlines was to paint him in chronological order.” With 16 damage variations, the challenge of updating UVs and repainting elements was a long-winded task. Holt was able to pull it off efficiently thanks to his work with colleagues ahead of time, mapping out all damage and sub-damage states.

Robot Locomotion

It was Sharlto Copley who took on the considerable acting challenge of portraying the AI-with-attitude, Chappie. Image Engine eschewed motion capture for the task, instead having Copley and various stuntmen act out the role in the plate, which Image Engine animators could then match to via a process known as ‘roto-mation’. Along with tracking markers, the grey on-set costume worn by the performers included elements that bulked them out to Chappie’s larger size, and also restricted their movement in order to make any fluid human movements feel more robotic.

Shane Davidson, compositing supervisor, explains further: “The most challenging aspect of Chappie was the sheer volume of digital paint work that needed to be done. Neill chose to film Sharlto Copley (or other stuntmen) for nearly every shot of Chappie in the film in order to keep the actor interaction authentic and to retain the nuances of Sharlto’s acting.”

“Some of the paintwork was fairly straightforward. There were clean plates (alternate takes of the same or similar action without the actors) or other references to draw from. Other shots were extremely complex, involving painstaking recreation of actors or moving set pieces.”

One example Davidson highlights is a scene where Chappie follows characters Ninja and Yankie into the dogfight arena. This required Copley’s performance to be removed, and then the actors to be reconstructed whenever they walked in front of Chappie and were revealed by the animation. “This involved hand animating and warping cloth as well as rebuilding sections of the actors tattoos while they are walking through various light sources,” says Davidson. “One shot alone took nearly two months to complete… And there were several equally complex shots! I can’t heap enough praise on the compositors or on Casey Yahnke, our BG Prep Lead and the entire paint department for pulling off such great work.”

This process of animating Chappie over Copley was initially carried out in a swift two-month period, as Blomkamp wanted no member of the public to see the human actor in the role prior to the film’s release. This was a hugely important creative task for visual effects in that it cemented in the mind of the filmmaker how important it was that the digital character carried the day for the audience and needed to prove from day one that this was indeed possible from an emotional perspective. Image Engine’s animators hand keyframed on top of Copley’s performance in order to match it, with great results. Working with RED EPIC plates and director of photography Trent Opaloch’s anamorphic lenses, Image Engine engaged in a considerable process of matchmoving, tracking and plate preparation.

Additionally, as the crew had to work with the numerous different damage states for Chappie – he takes quite the beating through the movie, after all – this required one main Chappie asset in Maya, which could be switched out for the dozen-plus different damage states as and when required.

But it’s the little touches that make Chappie really special, and Image Engine made sure to get those spot on. There’s the 5,500 individual links of chain in around 450 shots that made up Chappie’s gangsta bling, for example, or the visual tics of Chappie – added in order to make him a more relatable, human character – which were a case of Copley’s subtle acting talent being capitalised on, and exaggerated by, the animation team.

With a polygon count ranging from over 3.2 million to almost 4 million – and being made up of 2,740 objects, around 400 bolts, 40 pistons and 161 wires and hoses – Chappie ended up being a very believable automaton. And a surprisingly human one to boot.

Practical Paintwork

Texturing also played a large part in making Chappie look appropriately realistic in his Johannesburg surroundings. Image Engine had a great deal of visual effects shots to put together, and all in all ended up with more than 56,000 texture maps, with a huge 538 UDIM texture tiles. The texture memory required to produce the incredible-looking work seen throughout the film tipped the scales at just over a whopping 152GB.

“We made sure to collect as much photographic reference as possible before we started painting the digital versions,” says Holt of the textures. “The real effect the practical versions had for us was providing exactly what Neill [Blomkamp] wanted to see, not only for all the characters in the film but also all of the intricate progressive damage states Chappie experiences.”

Matching the paintwork to the practical models and real world examples was a real challenge. Blomkamp was adamant that all artistic decisions were to be grounded in the real world – no flights of fancy – meaning every texture had to be matched down to the last scratch and moisture stain.

“The practical details, provided by WETA Workshop, were invaluable in making the texture process much more effective and believable,” continues Holt. “It’s always better to paint textures based on real world examples than your imagination. A tremendous amount of care and attention was spent on analyzing the practical paint jobs and figuring out how to deconstruct the textures in order to build them back up layer by layer digitally in a completely non-destructive workflow.”

Bringing a Robot to Life

Chappie doesn’t mark the first time Image Engine has worked with Neill Blomkamp, nor is it the first time the studio has produced robot characters for the director. A number of military, police, medical and security droids were also created by the studio for 2013’s Elysium. As such, the team was able to bring much of its previous experience to the fore.

Earl Fast, one of three lead animators on Chappie, explains: “For Elysium, we had a handful of shots that required the addition of several police and security-type droids. The work we did with those droids was almost exclusively rotomation, with a few shots that were added during the editorial process that we ended up shooting motion capture for.

“It was on this project that the benefits of using rotomation really became evident, serving the twofold goal of getting the performance that Neill wanted on set and efficiently recreating that performance on the CG droids.”

However, while Image Engine’s past experience was a great help, this time around there was one major difference: the main character – an almost featureless bot – had to emote and connect with the audience. This aspect of Chappie was a game changer for the studio.

“The challenge with this film was that Chappie was going to ‘come alive’, so he needed to express a full range of emotions as he interacted with his environment and those around him,” says Fast. “We were very confident that we could transfer all we had learned on Elysium to achieve the desired performance with the non-emotive scouts, but that extra level of emotionality and the need to create a character connection with the audience for Chappie was still an unknown to us. That’s where a lot of testing took place.”

Chappie’s limited expressions – with static lights for eyes, no mouth, simple ears/antennae, and a brow and chin bar being the only articulating parts – meant it was a challenge to humanise the automaton. “We quickly realized that subtle timing and unifying the movement of these parts to Sharlto’s performance was the right way to go,” explains Fast.

“We often had to compensate the overall head rotation to account for eye lines. Sharlto is able to look around while keeping his head still but Chappie is not – as such we often found ourselves adding his eye movements into the movement of Chappie’s head so we could retain the on-set performance.”

The Assembly Line

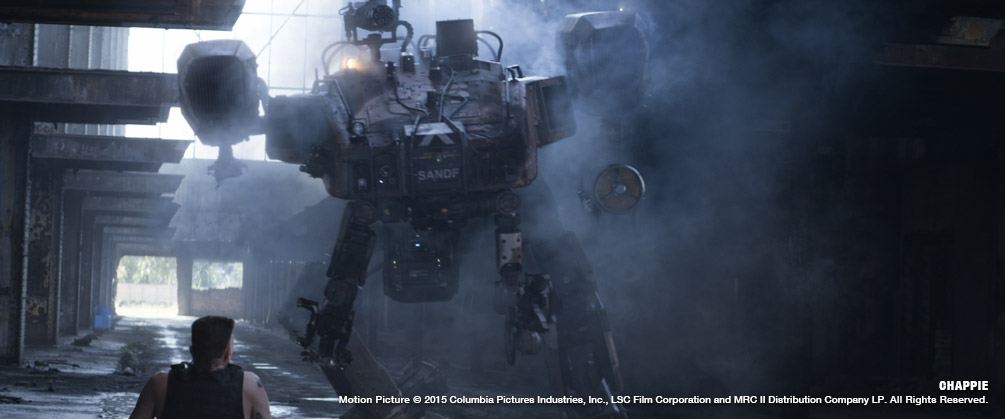

While the movie may be named after him, it isn’t just Chappie who appears on screen. Image Engine was also responsible for the scouts, the Moose, the prototype droid and any other robo-people who show up.

With the generic scouts and prototype – Robot Deon – the approach was similar to Chappie himself. Grey-suited actors were filmed and animated over in painstaking detail, albeit with less bling on show. While the supporting cast doesn’t see the same level of visual development as the protagonist, it did still require differing states of damage and vandalism as the story progresses. Altogether Image Engine crafted 28 unique robots for Chappie.

But one robot not included in that list is the formidable Moose – a walking (and sometimes hovering) tank that strikes fear into the hearts of anyone who encounters it. And then blows them up. The Moose was based on renders initially created by Blomkamp himself, but the process of inserting it into the movie differed from that of Chappie and the scouts – in part because it would be rather difficult to get a large enough actor to portray it!

Instead, a matchmover held a pole with a tennis ball marking the eye line – an old-school solution for a very modern production. Afterwards Image Engine needed to paint the crew member and his pole away, replacing him with the towering Moose. The machine consisted of over six million polygons, 2,785 objects and around 1,000 UV tiles.

The Moose

“The Moose robot was an entirely different scenario to Chappie, as we had no practical movements to match,” explains Poon. “Our biggest hurdle was making sure that each part’s function made sense, especially with the large amount of unique pieces.

“The quantity of cables and hydraulic hoses on Moose provided another challenge. In the beginning, we tried to use an automated rigging setup for the hoses, but to get the proper weight and subtleties our Creature FX team ended up having to create a separate FX rig and run simulations on a per shot basis.”

One of the early problems the team encountered with the Moose was a lack of reference: “There aren’t a lot of 12-foot tall walking tanks around to go out and film!” laughs Harvey. “But seriously, just finding that balance of reality, intimidation and scale was something we really worked on a lot across all the departments.

“There was also a lot of back and forth spent working out how the Moose would look when flying,” continues Harvey. “We had to think about how his legs would hang, how maneuverable he would be and so on. One thing we added to him in general, but actually started out when thinking about flying, was a sense of vibration that ran through him – not just shaking his parts, but actually warping the paneling. The frequency and amplitude of this jitter could be adjusted by the animators as needed.

“When the Moose flies around, we had a drone team that would fly a drone around for the eyeline – that way there was always something for the actors to look at and react to.”

The Moose causes a lot of destruction in the film – orchestrated by special effects supervisor Max Poolman – and the team were always looking for an opportunity to turn things up to 11. “There was one scene with Moose that we re-shot because we thought we could go bigger,” recalls Harvey. “On the day it went off we said, ‘Holy crap Max, what did you do?’, and he said, ‘Well you guys said make it a little bit bigger’ – these things were triple the size! He was always happy to make things explode or go bigger, especially where the Moose was concerned. That thing is a real tank.”

The Final Touches

Using the likes of Maya as a primary 3D application, Shotgun for asset management and ZBrush for modelling, Image Engine also channelled its expertise into creating bespoke software solutions. These included elements like an advanced shader layering system, allowing for realistic soft transitions between material properties; auto-simulated renders for necklace and cables; and even a custom audio tool to help sync up Copley’s audio track to Chappie’s mouth light.

The final 3D pipeline for Chappie was reliant on animation in Maya, which was also used for the majority of the modelling work. Effects came through Houdini; one of the in-house shader rendering solutions through 3Delight; and compositing via NUKE. MARI also featured in texture work (with Maya’s UVLayout plugin used for UVing), as well as RV and Houdini. Overall a great deal of varied software was used – unsurprising for a production of this size.

Holt explains why MARI was his tool of choice for the texturing work: “With the introduction of the layering system in MARI, it made painting Chappie and all the other assets exponentially faster and more efficient,” he says. “The ability to maintain a 100% non-destructive workflow thanks to the layering system not only yielded more successful textures, but also saved us copious amounts of time in the revision process of the textures as they went through various stages of review.”

Another bespoke solution to a very specific problem came when it was decided there would be no ‘cheats’ in how Chappie was animated – his joints would function how they would in real life. Unfortunately, those joints didn’t function like human ones, and the existing IK solvers in Maya couldn’t handle the number of axis-restricted joints throughout the robot’s body.

“The animators wanted to directly drive Chappie’s hand and wrist positions without having to exactly define all intermediate joint rotations manually, just like they were used to form standard human IK arm solutions,” Poon explains. “Unfortunately, Maya’s standard IK solvers are not able to handle that many degrees of freedom, so we had to work closely together with the R&D department to develop an alternative solution. Programmer Luke Goddard developed a custom IK solver that was able to (theoretically) solve an infinite amount of joints at the same time, all without the need to run a simulation.”

Managing the Actor

With such a large volume of work – over a thousand complex visual effects shots – Image Engine leaned heavily on its production management team. Lead by visual effects producer Geoff Anderson and visual effects production manager Asal Nikkah, the Image Engine team scheduled and oversaw all aspects of the visual effects production process.

“Editorial was right around the corner, here in Vancouver” says Anderson “so being able to have a presence there when needed was a huge help – but more so was having Neill on-site at Image Engine on a frequent basis for reviews.”

The Sum of His Parts

Overall, Image Engine is extremely pleased with the final product in Chappie. “I am fiercely proud of the work that the crew did and what we were able to achieve,” says Harvey. “I can only hope that audiences connect to Chappie and that he goes down as a memorable character in films for years to come.”

“We’re so proud of the Image Engine crew” says visual effects producer Geoff Anderson. “This project was an around the clock commitment for our team for nearly two years and I think the final results speak for themselves.

“The original award was 720 full computer generated robot shots: a tall order for a smaller studio, so we had to work efficiently,” continues Anderson. “We put a large majority of our efforts in the front-end portion of production with the building of the Chappie and Moose assets, ensuring that ample time was spent in modeling, texturing and look development. Even though it seemed like we were spending too many of our ‘man-days’ in this area, we were able to produce vast efficiencies once we hit shot production. The assets were flawless, so when these were handed over to a crack team of professional VFX artists, we soared through shot production, gaining any loss back and the ability to tackle the 300 additional computer generated robot shots in the remaining three months of the project, getting our count above the 1000 shot mark!”

For Anderson, Chappie’s success was all about thinking ahead: “We had a plan early on. We knew what the priorities were. We worked through the issues from the beginning. It was a tremendous amount of work, but we put ourselves in a comfortable position to execute, and execute well. Also, I can’t say enough about how great it was to work with Neill to achieve Chappie. Neill’s trusting manner and efficient direction gave us a huge leg up in terms of managing this production. And it shows in the quality of the work.”

The sheer amount of work put into the project by the team at Image Engine really does show in the finished movie, and there was no one element alone that made Chappie the character he ended up being. It really was an ensemble effort, as Harvey explains: “It was down to the fantastic concept art; the focused efforts of the asset team and practical builds from Weta Workshop; Shartlo’s performance; the on-set crews and camera department; Neill Blomkamp’s direction; our layout and BG prep teams; phenomenal work from the animators; and the scrutiny of detail in the lighting and compositing departments.

“Chappie is the sum of his parts.”