Kin Case Study

Case Study

Image Engine's stunning work on Kin involved futuristic weaponry, holograms, portals and a sequence in which time is brought to a standstill.

Three years ago, siblings and directorial duo Jonathan and Josh Baker created Bag Man – a 15-minute short that paired subdued, indie drama with a slick sci-fi twist.

Now, the brothers have expanded on this core concept in their first feature-length tale, Kin. Similarly to Bag Man, Kin relays the story of real people who find themselves in possession of powerful technology – technology they’re perhaps not ready to handle.

Whereas Bag Man had but a short amount of time to present its vertical slice of narrative, Kin spends its longer runtime recounting the broader story of teenager Eli. After discovering a mysterious weapon among a mass grave of cremated bodies, Eli soon finds himself pursued by a sinister group of enigmatic hunters looking to reclaim their tech.

Given that Kin’s heart-pounding chase contains futuristic weaponry, holograms, portals, and one sequence in which time is brought to a standstill, visual effects were required alongside the beautiful in-camera cinematography. Image Engine’s talented artists were brought on board to create these visuals, who worked on the indie project alongside blockbusters like Logan and Power Rangers.

Kith and Kin

Image Engine was a keen to get involved in Kin, having previously contributed triple-A visuals to lower budget Hollywood dramas such as Child 44, Zero Dark Thirty, and Detroit..

The Baker brothers invited the studio into the process from the very earliest planning stages, giving Image Engine’s artists plenty of time to fully understand the directors’ approach, thinking and filmmaking philosophies. This time was also spent on preparatory technical processes: Image Engine took the opportunity to previsualize key visual effects shots, and then, during principal photography in Toronto, Canada, visual effects supervisor Dave Morley was sure to be on set to oversee any scenes requiring post.

“It was a really collaborative process,” says Morley. “Jonathan and Josh were totally open to the way we work at Image Engine, and even though Kin was an indie film there were no limits in terms of creativity. We got what we needed to create great visuals, with no compromises.”

Alien armoury

Kin’s narrative unfolds around the powerful alien weapon discovered by Eli. Given that the hardware sits at the center of the story, it was important that it felt rooted in reality in all shots. Image Engine worked to develop an aesthetic that not only demonstrated the weapon’s otherworldly origins, but also felt a part of its surrounding environments.

With this in mind, Image Engine augmented the rifle with holographic readouts, which would shift depending on the weapon’s current mode. The heads-up-displays (HUDs) were designed by UI designer GMUNK, and were then ingested at Image Engine for compositing into live-action plates.

“We were very lucky to have Luis Almazan on our team – a very talented compositor and motion graphics artist,” says compositing supervisor Keegen Douglas. “He went to town on the project! He pulled in all of GMUNK’s work and dissected it, rebuilt it and re-rendered it all for an amazing final effect.”

Image Engine’s mandate also included any effects prompted by the firing of the weapon, ranging from destructive environmental effects to disintegrating targets.

“Gun blast FX consisted of all kinds of simulated geometry,” explains FX TD Lukasz Sobisz. “There were pyro sims for both the trail and muzzle flash, and the velocity fields were driving layers of particle trails, plasma core and embers.”

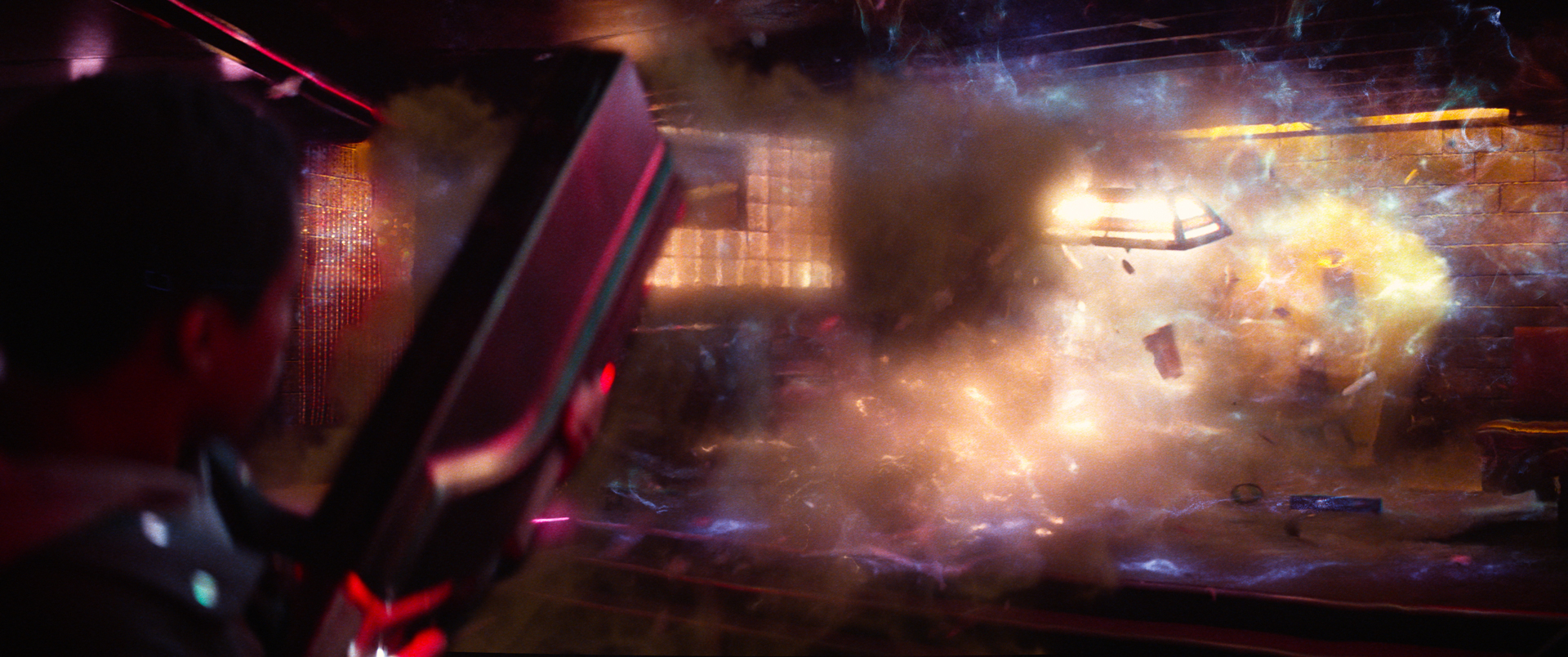

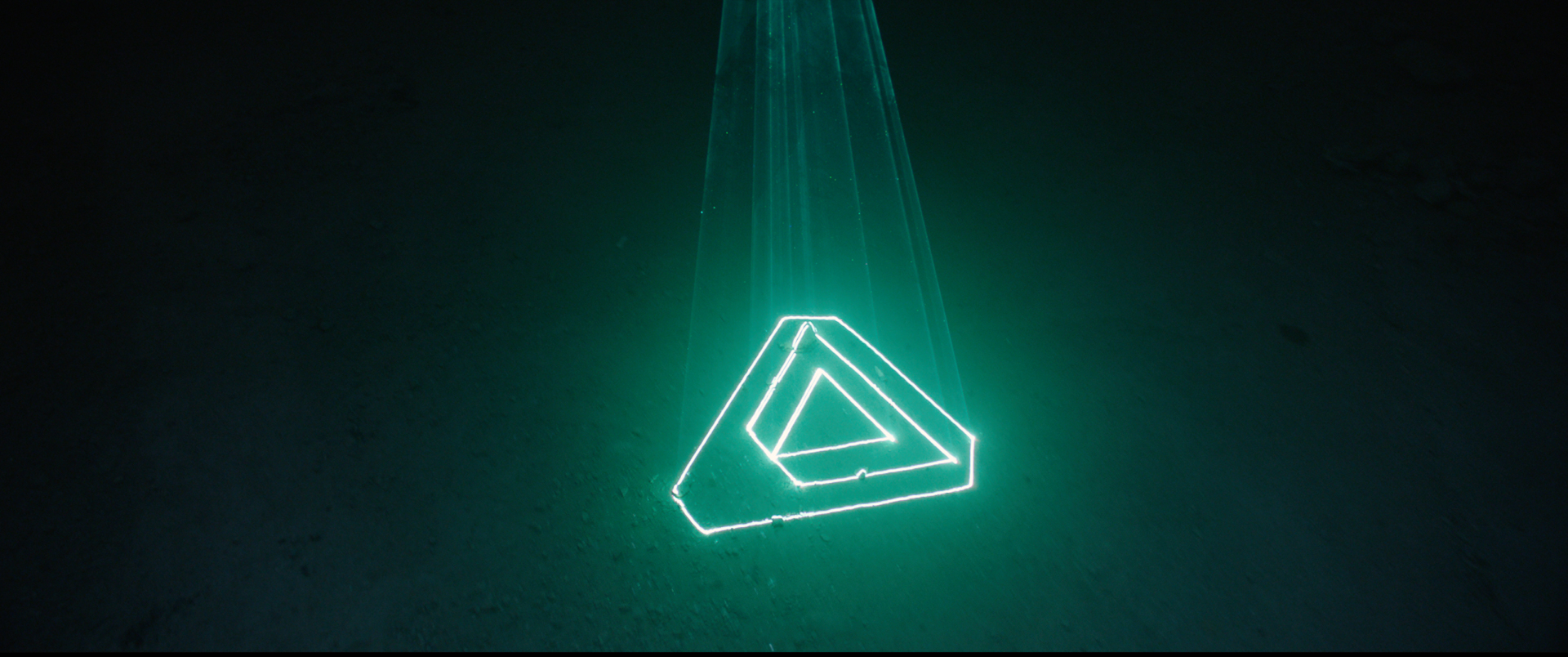

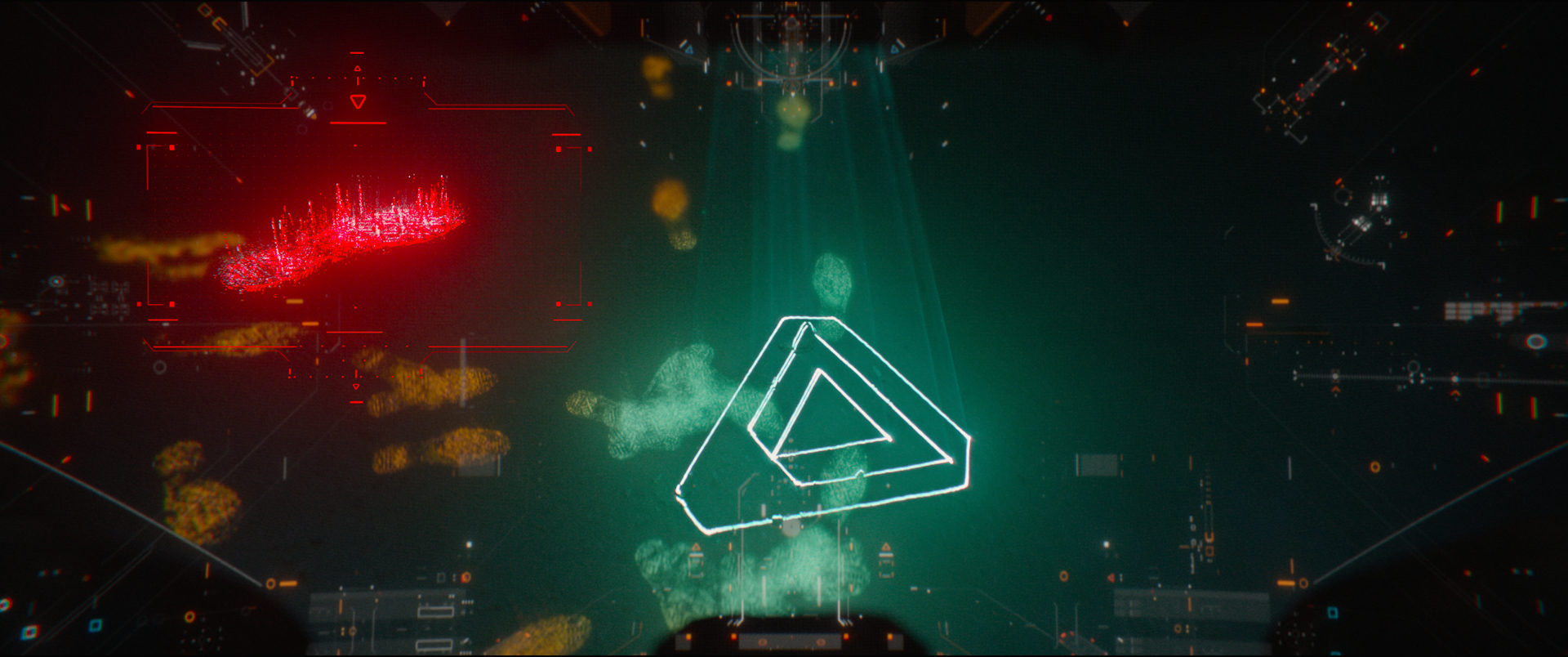

Holographics

In one scene, Eli’s pursuants – known only as the ‘cleaners’ – use alien technology to locate their target, tracing the signature given off by the weapon when last fired. They do so using an orb, which splits into pyramidal shapes and holographically projects the moment the trigger was pulled.

This hologram comprised a complex mix of some 600 separate 3D rendered elements. What’s more, the on set location contained numerous mirrors, making things even more challenging.

“We had to do a lot of work in terms of the layout of the room and rendering reflections in the mirrors,” says Morley, “The cleaners also wore helmets with shiny black visors, which meant even more mirrors to work with!”

Thankfully, the artists were aided in the creation of the hologram by carefully considered on-set lighting, which could be easily matched in post.

“It felt like the Cleaners that were moving around this room and the room itself had this source-y, kind of orange light on them, and once the holograms were in there, you kind of didn’t question it,” outlines Morley. “If we’d showed up without that kind of those lights in there, it would have looked lame in a way.”

On-set photogrammetry data and simulated point-based procedural structures helped to further build the multiple layers of deformation and animated noise that comprised the hologram.

“We achieved readability by dimming occluded areas with camera culling, which was running at render-time as a graph in Gaffer, Image Engine’s node-based application framework,” says Sobisz. “To further ground the effect within the on-set environment, everything was covered with a subtle layer of volumetric fog, which nicely combined with the projection beams and smoke slowly travelling through it.”

These elements were finally composited together; a mammoth task in itself given the large number of layers. “It was quite interesting to open up the compositing scripts,” says Douglas. “I think one of them was one of the biggest comp scripts I’ve ever seen in my entire life!”

A moment frozen in time

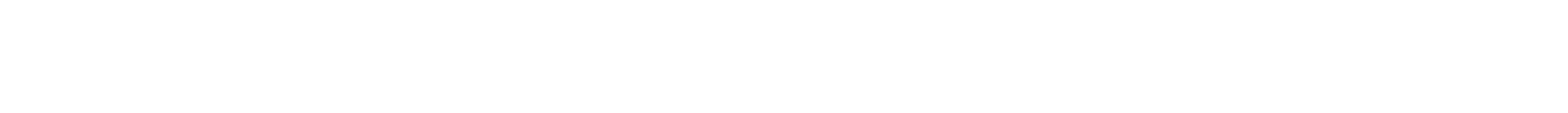

One of Kin’s standout visual sequences takes place in a police precinct, where the insidious cleaners use a grenade capable of freezing time. The result is brutal yet spectacular – police officers are suspended in mid-air among still-life eruptions of fire, glass and debris. The frozen scene is stretched across several minutes of screen time, which demanded a fair amount of VFX problem solving.

Thankfully, Image Engine had plenty of expertise in the area, given its experience on 2013 blockbuster R.I.P.D.’s frozen-time opening.

To start, artists prevised the sequence, creating assets that proved useful on-set. For instance, using the designs created at that stage, the actors could be rigged mid-fall, keeping them as static as possible while also ensuring they remained comfortable: “The production basically welded a whole bunch of steel together, giving the actors a really nice, platform to lie on,” says Morley.

VFX artists painted out these rigs and added simulated debris and glass shards into the final scene. “Adding the glass into those shots was tricky,” notes Douglas. “Thankfully, our lighting team really nailed their part of the process, so we just needed to comp in some extra pings and reflections that set the glass into the physicality of the scene.”

Image Engine also added slight parallax shifts to sequence, amping up the audience’s sense of movement and perspective. LIDAR imagery captured on set meant that the implementation of this parallax was simple and effective, making for a subtle yet powerful sense of immersion in the scene.

A new dimension

When the cleaners finally leave Eli’s world they do so via ice-like portals. These interdimensional gateways appear in vortexes of shattered air, and coruscate with continually growing and fracturing ice formations.

Image Engine’s FX simulation team was mainly responsible for this effect, which they built primarily with Side FX Houdini.

“The result of the main simulation was used to produce a number of secondary effects,” says Sobisz. “These included dry ice pyro simulations, particle based frost, and additional thin layers of ice, all of which helped to integrate the portal effect into its surrounding environment.”

“The portal was an interesting challenge, as it’s a sci-fi trope but one that audiences haven’t seen in this way before, so we were defining a new look,” notes lighting lead Martin Bohm, who adds that the success of the effects simulations also came down to placing a large emphasis on on-set preparation and lighting.

“The production used a light source to represent the CG portal on set. That gave us a perfect lighting match, which makes life as a lighting artist much easier. This on-set preparation for VFX was invaluable, and shows just how familiar the directors were with the process. They knew exactly what they were doing.”

As visual effects supervisor, Morley says that Image Engine’s on-set presence greatly assisted the studio’s work on the production. It helped, too, that the Baker brothers remained completely open to Image Engine’s approach to VFX, ensuring the right steps were taken for every shot.

“That really speaks to the experience of the directors,” states Morley. “They have an impressive effects background and they know what it takes to make a solid shot. Working alongside them was a real pleasure, and the end results are spectacular, especially so considering the indie scale of the production.”

“Working with the brothers felt like working with kids we grew up with on our block.” said visual effects executive producer Shawn Walsh. “The way that they use references to define work, listen to our feedback and decide the direction of our visual effects in a clear and engaging way is exceptional in our experience. We all just want more!”