Game of Thrones: Season 7 Case Study

Case Study

Experience the thrill of the Battle of the Goldroad, also known as the "loot train attack," in Game of Thrones season 7 through the lens of Image Engine's award-winning VFX work. Winter has arrived, and violence ensues.

Game of Thrones season seven is less Machiavellian and more McTiernan. The show’s undercurrent of unscrupulous scheming is washed over by a roiling spume of surface conflict. Secrets are out. Events have come to a head. Winter has arrived. This panorama of violence is witnessed with no more clarity than in episode four’s the Battle of the Goldroad, known colloquially as the ‘loot train attack’. Discover Image Engine’s award-winning work in this epic battle.

In this pivotal sequence the combined Lannister-Tarly army return east to King’s Landing following the successful sacking of Highgarden. The Mother of Dragons has other plans for the convoy, however: Daenerys Targaryen swoops down atop her prize beast, the magnificent Drogon, littering the fields with burned-out husks of Lannister soldiers and streaking the green grass with crimson.

It’s one of the season’s standout moments – and one that could only be brought to life by the application of the latest in creature VFX. Image Engine was on hand to take point across this entire sequence and beyond, acting as the lead vendor responsible for Daenerys’ dragons.

“In previous seasons of Game of Thrones we mainly worked on set extensions, digital environments and gory battle sequences,” says Tyler Weiss, VFX producer on Games of Thrones season seven. “We built up a lot of trust and momentum with the production team over the years, and that opened the way to season seven, and the big step up into the world of creature work we’re so familiar with at the studio.”

“Steve Kullback said to me” recalls Shawn Walsh, VFX Executive Producer, “I know that Image Engine is capable of very complex creature work like the raptors for Jurassic or creatures for Fantastic Beasts. Would you consider assembling a team to take on Drogon for season seven? It’s gonna be bitchin’!”

For Thomas Schelesny, who was brought on as VFX supervisor for Game of Thrones season seven, the level of trust placed in Image Engine has been humbling. “The show takes a circumspect approach to the kind of work they will trust to each vendor in terms of their ability to deliver to the level of excellence the series demands,” he says. “Seasons five and six were a ‘getting to know each other’ experience. Season 7 was a really, really big step up from that…”

Bigger means better

The bulk of Image Engine’s primary work is witnessed across the loot train sequence, but the team also provided draconic visuals for two further scenes: Daenerys’ execution-by-dragonfire of Randyll and Dickon Tarly, and a later sequence when the show’s principal characters meet in the grand amphitheatre of the Dragonpit.

“The loot train sequence was the real biggie, though,” says Schelesny. “We animated and integrated Drogon, while partner vendor Illoura added the crowds and soldiers on the ground. Any time you would just see the dragon by itself, we would take those shots to completion.”

The brief for the dragons was simple: “It was size meets realism,” begins Jason Snyman, animation supervisor on the project. “The dragons have doubled in size from the last season – they’re as big as a Boeing 747 – so we needed to think about how to communicate that scale via animation.”

As with any creature-based project, Image Engine started by looking at animal reference, using footage of large reptiles, eagles and bats, but in this case multiplying that reference by 100. “We also looked at reference of things like the tarp of a tent and how quickly that would be filled with air, how wind interacts with the sails of a yacht, and how airliners stay in the air,” says Snyman. “We had to sell the sheer scale of a 747 but make it work as a dramatic device.”

Image Engine artists considered a variety of biological and physical factors to achieve this, including wing and flight dynamics: “We considered things like how many flaps would a creature of that size need to stay aloft, or in what situations would a glide be more realistic,” says Weiss. “If you have too fast of a flap, or too much range in the wing momentum, you can make a big dragon feel small very quickly.”

More than skin deep

Although the dragon model itself was originally created by another vendor, Image Engine updated the asset to suit the demands of the sequence: “We refined the texture maps so they worked for the camera angles and distances between the dragon and camera” explains Schelesny. In order to sell the scale, we added a whole level of micro-detail that didn’t exist in the base textures. For example, when Drogon’s wings open up you can see veins and surface details in the membranes and between his neck frills. We completely reworked those features because we had a series of shots where we were very close to Drogon’s back, neck and head. ”

However, defining biological realism meant thinking about the dragons both externally and internally. Artists contemplated dragon musculature and physiology, implementing many subtle touches that reinforce the illusion of a mythological creature wrought in flesh and blood.

“You need to think about muscles compressing and fibres stretching, influencing movement before it’s even happening,” says Snyman. “With Drogon, his musculature would flex just before the wings would begin to move. His shoulders would come back and his chest would heave before the wings beat back down.”

Image Engine also added several controls to Drogon’s biology, enabling them to control how much air filled the wings while gliding and the dynamic flutter and billowing it would cause.

Intelligent beasts

Small scale thinking accompanied big in the creation of these aeronautic leviathans, with indicators of intelligence layered beneath the dragons’ vicious facade.

“The dragons are like loyal lions. There’s power and violence there, but personality too,” says Snyman. “In the loot train sequence, HBO VFX supervisor Joe Bauer told us that Drogon should be feeling ‘glee and happiness’ at this attack, so when he’s charging up his fire blasts there’s a sense of anticipation to his body language.”

In the Tarly execution sequence, Image Engine conveyed animalism alongside control – a challenge in some ways more demanding than that of the more action-packed shots, given that Drogon is completely at rest.

“He’s sat atop a giant rock and behaving. He’s aware of his surroundings, but not doing anything as attention-grabbing as breathing fire,” says Jenn Taylor, animation lead. “We focused instead on instilling him with a sense of purpose and latent power through naturalistic mannerisms such as his breathing and slight muscle flexes. He’s like a chained animal, waiting for Daenerys to give the word to explode.”

Pre-animating dragons

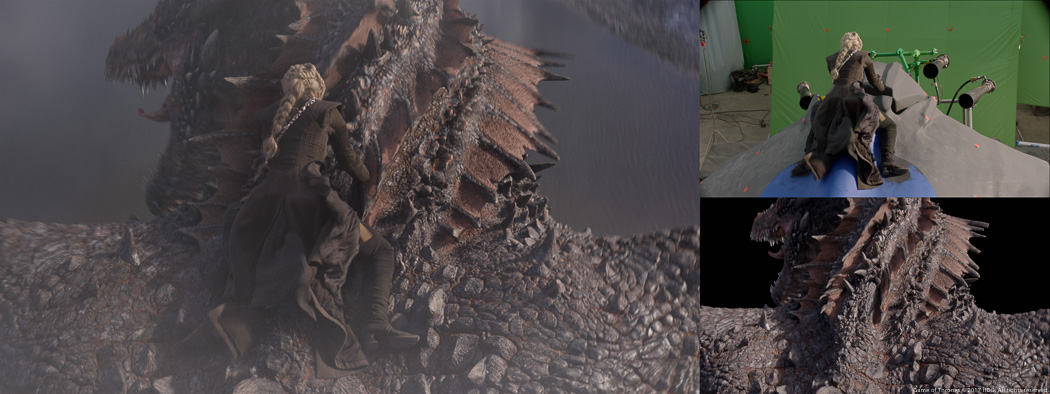

Image Engine didn’t just give life to the emotional bond between Drogon and Daenerys, but also their physical connection. A process named ‘pre-animation’ – developed specifically for Game of Thrones – enabled the team to place the live action actress atop the digital Drogon with pixel-perfect accuracy.

Pre-animation took place after previz, but before production of full animation. During the pre-animation phase, animators would define the movement and cadence of Drogon’s actions in the shots containing both him and Daenerys. This information was then provided to the on-set production team, who shot Emilia Clarke against a green screen background and riding a robotic motion base, the movements of which were driven by the pre-animation data.

Image Engine could then take these plates and composite the image over the animation outline, meaning the in-camera footage moved entirely in sync with the the CG dragon’s motions. Artists also created a digital version of Emilia Clarke to add shadows to Drogon’s back, reinforcing the feeling that her character really was astride this magnificent animal.

“This was a fantastic approach, as it gave us a headstart in terms of defining the dynamic in-camera movements that would also be appealing in animation,” says Taylor. “We made sure to follow real-world rules, ensuring Daenerys never looked like a doll or a toy on Drogon’s back.”

Pre-animation was also used to connect the torrents of flame that emerge from Drogon’s mouth to the movement of his mighty neck and body. “Full credit to Joe Bauer, the production VFX Supervisor, on this – any opportunity to shoot something for real, he would take it,” says Schelesny. “Virtually every time you see Drogon open his mouth and fire comes out, it’s the real thing.”

“Production shot elements using what was, for all intents and purposes, a flamethrower slung under a cable cam rig. After translating our pre-animation scene files into their scaled stage environment, they used it to drive the rig, ensuring the flames were matched directly to the movement of Drogon.”

A powerful pipeline

Complex creatures on a TV turnaround is no easy task, but Image Engine is equipped with more than just experience: its robust pipeline is designed to tackle any challenge large or small.

“We studied our methodologies and combined as many processes as possible, because if you just take a standard filmmaking approach and apply it directly to Game of Thrones, it simply won’t pan out,” says Schelesny. “We work to optimize every step so the artists can focus on the art and avoid immaterial tasks.

“For instance, on this season of Game of Thrones, we ensured our dailies were delivered with as much data as possible,” he continues. “Information about the dragon relevant to the production would be automatically burned in, such as camera focus length, speed, height of the dragon, shadows, motion blur settings – all generated in real-time without artists needing to collate it. We’d also auto-render multiple views of each animation submission, to allow the client to quickly analyse the performance from every angle.”

This was a huge benefit for the show’s animators, who could render out a final pass with all textures and the latest comps and ship it with each daily. This meant any necessary changes could be made on the fly, without need for a laborious repeat process through the comp or lighting departments.

“I could do things like change the angle of Drogon’s head slightly to get more light on his face, which is something you would normally see later down the line once the shot went through lighting,” says Snyman. “We could have that change as part of animation as early as possible, and see what the shot looked like straight away! This enabled our artists to focus more on the creative side of the work, and less on the time-intensive technical processes.”

“After completing the season seven work, we got together and had a postmortem about how we can further improve in future,” says Schelesny. “We’ve already done some great work that will enable our artists to focus less on process and more on the final result.”

A shared experience

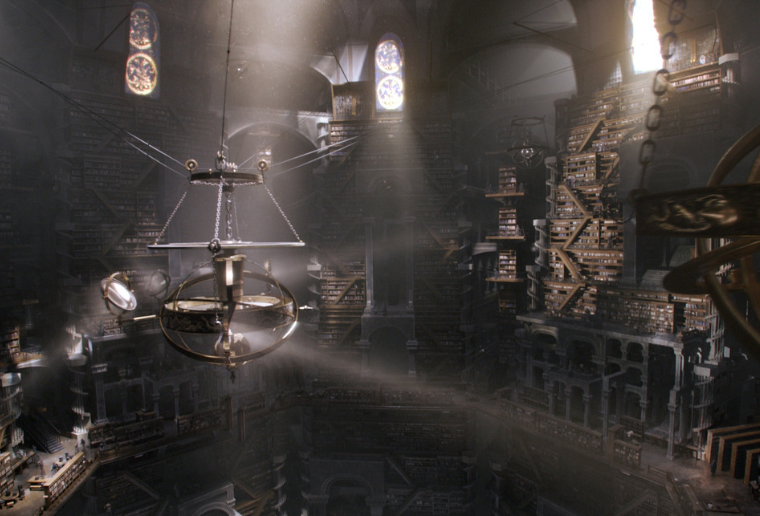

Image Engine accompanied its work on the dragons with an assortment of work ranging from matte paintings to digital environments. This included shots in the maester’s Citadel – an environment Image Engine had created for season six, but this time requiring a 3D camera movement through the cavernous space.

“This year there were big camera moves within the digital Citadel, which meant that some of the tricks you could use for simple pan and tilt were not possible,” explains Schelesny. “The same CG supervisor who did that work for season six, Edmond Engelbrecht, dug himself in deep, unpacked everything from the previous year and stepped up so the environment would support this 3D camera work.”

Nevertheless, the team’s core role on the season was clear: dragon wrangler.

“All of the animators are huge fans of the TV show, and just love creating creatures, so this was the brief from heaven!” says Snyman. “We went into it with everything we had, making everything as vicious and chaotic and edge-of-your-seat as we could. It was a level of dedication to refined animation rarely seen on a television show.”

For Schelesny, the sequence provided an opportunity for him to witness something he’d never experienced in his 25 years of VFX: the audience reacting to his team’s work.

“Before our work on Game of Thrones season 7 I had never experienced the ‘reaction video’ on YouTube,” he says. “To see a room full of people watching the loot train sequence, screaming their heads off, clapping at the right parts, gnashing their teeth – that was emotionally rewarding to a degree I’ve rarely experienced.”

“So, to see that reaction was a great way to cap off the incredibly hard work Image Engine put into what was a very challenging, but very special season.”

“It’s a great credit to the whole studio and especially the behind the scenes work of our R&D and Pipeline specialists,” says Walsh “that this level of ridiculous complexity in a creature can be proven for television. The visual sophistication is totally on par with our film work and it was awfully good fun getting there!”