The secrets of creating real-looking CG digital doubles

Insights

Joao Sita discusses how Image Engine avoids the uncanny valley when creating CG humans, as it did for last year’s ‘X-Men for grownups’ film, Logan. He says crossing it requires less showing off, and more hiding behind the curtain.

By Joao Sita, Visual Effects Supervisor | March 8, 2018

If we’re going to cross the uncanny valley, then what the audience doesn’t see matters as much as that which they do.

This is a thought that I’ve let ruminate in my mind over some ten years of my career. 2008’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button was the source. David Fincher’s fantasy not only signalled a sea change in visual effects’ ability to augment a film’s narrative but also their ability to conjure photoreal CG actors indistinguishable from those of flesh and blood.

We’d seen many attempts before, but never as polished or accomplished as the digitally re-aged Brad Pitt. Benjamin Button inspired many more attempts at CG characters. Each was more impressive than the last: Tron: Legacy’s Clu, Star Wars: Rogue One’s Grand Moff Tarkin, and, most recently Blade Runner 2049’s superb revival of Sean Young’s Rachel.

Watching these artistic achievements on screen, I always return to the same thought. What’s working here isn’t what I can see. It’s what I can’t.

Hiding in plain sight

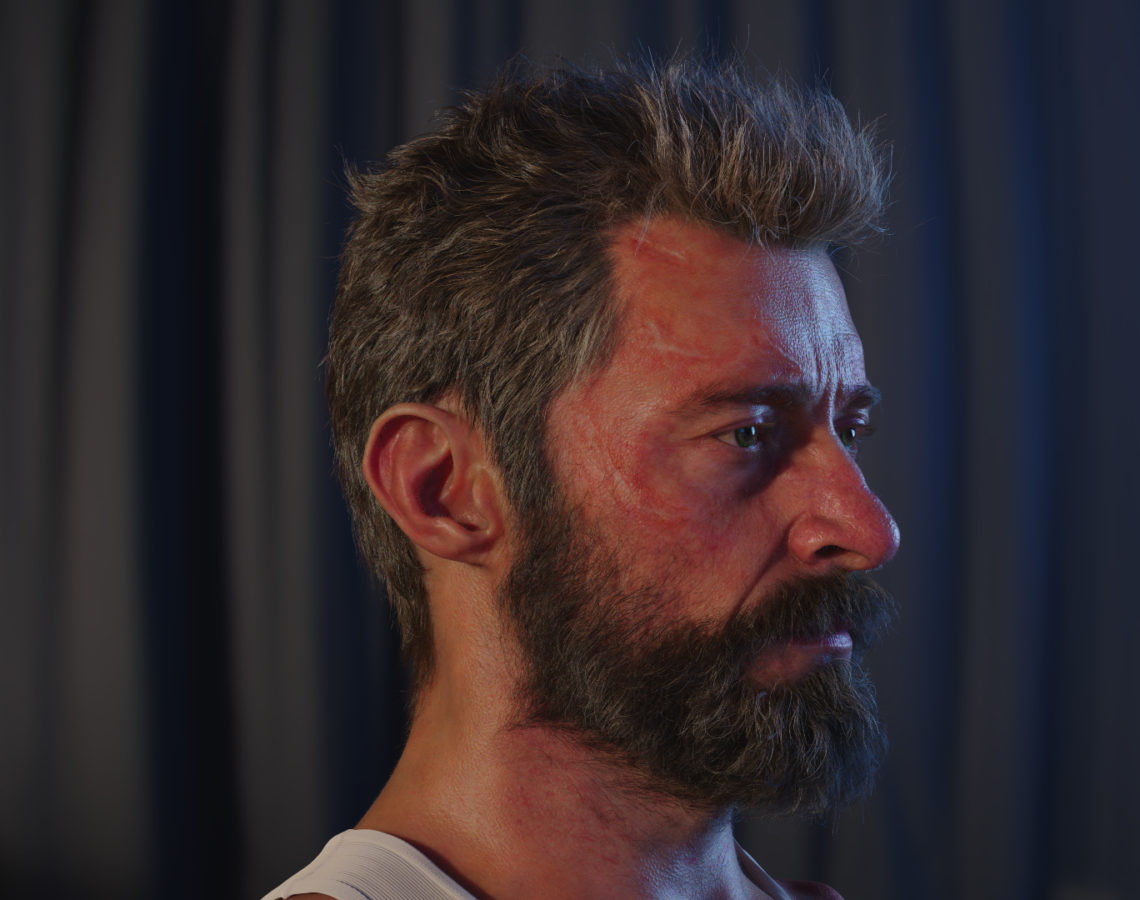

Image Engine recently delivered two digital clones for James Mangold’s superhero swan song Logan. These included doubles of Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine and Dafne Keen’s Laura.

The effort and attention to detail that went into these CG characters was absolute. The team spared no expense as they dove into every skin pore and considered every strand of hair. In the ten years since Benjamin Button we’ve seen a massive evolution in the technology and rendering power at our disposal, which enable ever-more granular levels of detail. But the tools are nothing without the hands that wield them. Our artists continue to amaze me, as they etch life into even static models of polygonal doppelgangers.

Our artist’s skill and craftsmanship was directly responsible for the stunning detail inherent in these models. They may have been working on a depressed and broken interpretation of the once-powerful Wolverine, but their work was nothing short of beautiful. Our digital Jackman and Keen (top and below, each next to the real-life actor) shared the screen with their real-life counterparts without audiences ever knowing they were there.

This hiding in plain sight was not only a key indicator of our success but a vital part of the creative process.

The harmonious whole

Think about any conversation you have had with another human being, face to face. You see them, but you don’t observe them. Subconsciously, you absorb hundreds if not thousands of micro expressions. Subtle muscular shifts and minute non-verbal tics communicate intent beyond the words employed. But you don’t always perceive them. You know if some is happy, sad, perplexed, or annoyed without consciously reflecting upon this information.

It’s this thinking that drives any digi double. Image Engine’s artists constantly considered imperceptible details that would add something deeper to a snarl or a stare in Logan. They wanted to communicate something more resolutely human from what was in actuality little more than a complex mass of polygons.

The stretching of skin around the lips, a tightening of the eyes, a split second shifting of the brow: all of these things working in concert. If the audience noticed any one of these factors alone it would pull them from the experience. They’d be back in the audience watching a digital facsimile. Working in harmony, however, the audience remains implanted in the world of Logan, watching amazing events unfold.

It’s an ethos that drives work across many visual effects. To use a different context, The Revenant’s bear attack works not because the audience is considering the rendering of the fur or the animation of a paw. They’re taking in the clumps of dirt hanging from the matted pelt; the shifting of the undergrowth beneath the bear’s weight; the strands of saliva dripping from its maw…all of these things as one harmonious whole.

Stay behind the curtain

Just as an audience should be watching a bear attack, not a complex collection of varied visual effects, digital doubles are only successful when the work conveys a sense of the whole. Artists should think about the human face not as discrete features, but as a collection of separate yet interconnected elements. If any one feature stands out from the whole, the audience will notice.

You need to be the Wizard of Oz, concealed behind the red curtain and summoning amazing visuals. Feel like you shouldn’t add a detail because “nobody will see it”? Audiences might not realise they’ve seen it, but they will. They’ll “see” it in the sense that they’re one step closer to the director’s vision for the story and more closely connected to the events on screen. They’ll “see” it in the sense that they’re not jettisoned from an experience by a crude digital human.

When audiences look at a digital double and don’t consider the VFX at all – when they can’t see the brush strokes, like a Georges Seurat seen from afar – that’s when digital doubles will go from noteworthy curio to something more significant.