Logan Case Study

Case Study

As the name would suggest, superhero movies tend to emphasize the ‘super’, showcasing dazzling preternatural abilities via the latest in visual effects. But Logan is not a traditional comic book movie. Learn how Image Engine’s team pushed the boundaries of photorealism to show the legendary Wolverine in an entirely new light…

Logan is a comic book movie unlike any other. Although it continues the tale of Marvel’s most grizzled hero – the laconic lone wolf Wolverine – its approach is altogether of a different ilk than the movies that came before.

This is the story of a wounded animal – the Wolverine of Logan less an unstoppable billow of blades and brawn, but a creature damaged both physically and psychologically, searching for a place in a world that no longer has need nor want of him. Bar one young and similarly taciturn girl, that is, whose powers are not dissimilar to Logan’s own…

It’s a story with all the raw emotion of a Johnny Cash track, with the visual effects used to emphasize the story, rather than overwhelm it: Wolverine’s iconic blades and a litany of mutant powers are on show, but the effects are altogether less flashy, and more steadfastly rooted in realism.

This presented a unique challenge for the Image Engine team, who came on board early in the 20th Century Fox production to deliver close to 300 shots. As primary vendor, the sequences created by Image Engine were extremely demanding – not only did the artists need to create mutant powers and adamantium claws, but also unfalteringly lifelike digi-doubles of the film’s core protagonists.

Read on to learn how Image Engine created these lifelike digital doppelgangers, delivering seamless visual effects indiscernible from the real thing.

Gritty and grounded

Logan’s shift in tone from predecessors The Wolverine and X-Men Origins: Wolverine impacted not only the storytelling, but also the overall aesthetic: “The production didn’t want traditional superhero movie, over-the-top effects,” begins Martyn Culpitt, Image Engine’s VFX supervisor. “Keeping it very real-world was the defining factor.”

Part of this raw and realistic approach included an unflinching approach to the representation of violence. As an R-rated film, director James Mangold and VFX supervisor Chas Jarrett wanted every punch, kick, and claw penetration to fully connect.

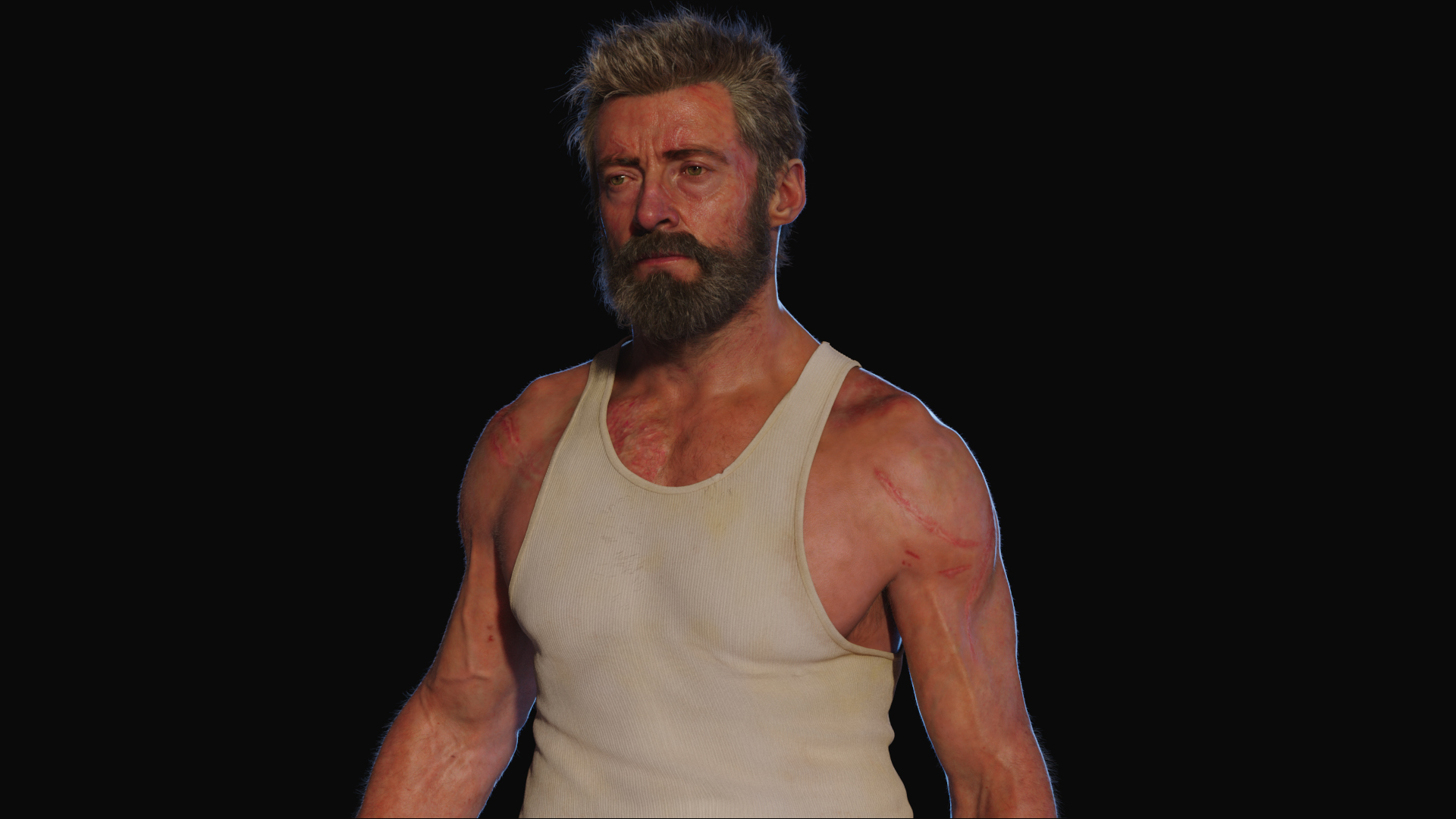

To represent this hard-edged violence while keeping the actors safe, Image Engine created full digi-doubles for both Logan and the young Laura (played by Dafne Keen). The team also created digital replacements for the numerous stunt actors who filled in for the leads.

These digital versions are impeccable 1:1 recreations, down to the subtlest skin pores and hints of emotion. Getting to such an intricate level of realism was no small task…

Digital doppelgangers

Image Engine’s digi-doubles have appeared in several projects, including Point Break, The Thing and R.I.P.D. Logan went beyond CG stunt doubles, however, requiring full-frame actors indistinguishable from the real thing.

Image Engine embarked on the challenge by capitalizing on past work, while also rebuilding aspects of its digi-double pipeline from scratch.

The process began with three months of work on body and facial rigs. Image Engine collaborated with the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT), using the latest incarnation of its light stage to capture extensive facial scans of Jackman and Keen under various conditions, as well as photogrammetry scans of their respective body proportions.

By utilizing years of research into image-based lighting, Image Engine captured the 64 different FACS (Facial Action Coding System) face shapes required for realistic animation. The system was also used to ascertain how light would hit the models from every possible direction by shining 346 different lights into the actors’ faces, one at a time.

“That was the ultimate reference for development work,” says Mathias Lautour, look development lead. “We could compare our render with the light footage, and ensure every frame featuring the digi doubles looked as close as possible to the real thing.”

Working from the base scans provided by ICT – which offered a mask-like high-resolution version of the actor’s face and skin – Image Engine fleshed out the remainder of the head and neck, cleaning up renders to align them with plate photography captured on set. They also used tools like Yeti to solve the hair, and Solid Angle’s ray-tracing Arnold renderer to achieve a realistic level of skin shading and sub-surface scattering.

Meticulous matchmoving and tracking ensured that replaced heads were perfectly in sync with the rest of the body. Shots of Keen in action proved challenging due to the wide-ranging expressions she would convey while attacking her foes, but a considered approach ensured that the audience would never know she was never actually in the frame.

X-24

Although these scans were also used as the foundation for head replacements during complex stunt sequences, they also played a much more prominent role: the creation of X-24 – a clone built from Wolverine’s genetic material. X-24 is the ultimate version of Logan; a younger, faster, more powerful facsimile.

A large chunk of X-24’s screen time sees Hugh Jackman performing the role. However, many times when he and Logan share the screen, a digi-double was used – one meticulously de-aged by Image Engine’s compositing team.

As compositing supervisor Daniel Elophe explains, Image Engine could multiply or remove detail in the facial scans, increasing or decreasing features around the forehead and under the eyes, for instance, which proved to be a “very quick and robust system to de-age the character.”

One of the film’s standout moments occurs when Logan and X-24 first meet. X-24 appears at the top of a flight of stairs, with Logan approaching from the bottom. X-24 descends and the pair end up face-to-face, the camera up close as the character and his clone share the same frame.

It was an incredibly demanding shot for two reasons: one, the audience would view the digital version of Logan up close and in incredible detail; two, the audience had the real-life reference of Jackman right there in the shot, increasing the chance for viewers to note discrepancies.

The result needed to be seamless. “That moment when X-24 comes down the stairs holding Laura is the single most difficult visual effect ever created at Image Engine, as much for it’s subtlety, as for the complex methodology we employed,” remarks Image Engine’s visual effects executive producer and general manager Shawn Walsh.

Face to face

“That was the first shot we started and the last shot we finished. We wanted to keep pushing the realism of it until the end, as far as we could,” says Culpitt. “You can scan a person and then put in those facial shapes, but if it doesn’t feel like them then it’s not going to work. It takes artistry and an attention to detail beyond the absolute to get something like this to feel right.”

When it came to the challenge of the ‘uncanny valley’ – the gap between humans and their replicas that can create a sense of eeriness – VFX supervisor Jarrett has an interesting response: “He simply said that there isn’t one – the digital double either looked like Hugh, or it didn’t,” recalls Walsh. “That was a massive challenge to our team, but it was also a cool thing to say, because it expressed a belief in us that we’d get there. It grounded us in terms of exactly what the purpose of our work was.”

During on-set photography, Logan was played by Jackman himself; X-24 was portrayed by a stunt double, whose face was digitally replaced with Jackman’s own.

Details needed to be more than skin deep, going beyond pores and eyebrow hairs – Image Engine’s artists needed to look at how these actors moved and reacted, down to the slightest flashes of emotion. Artists spent a great deal of time sculpting and adjusting animation to ensure X-24 looked like Logan in every scene, and tweaked lighting to ensure the digital model was lit exactly as the real-life reference of Jackman stalking down the stairs.

“We refracted light into his eyes using physical attributes, using a lens that would mimic real-life physics,” says Culpitt. “It ensured that these characters had a soul.”

Establishing detail

Image Engine spared no expense on the digi doubles, carefully modeling, texturing and lookdeving every detail, including the eyeballs of both the Logan and Laura digi doubles – after all, the eyes are the window unto the soul. Caustics, refraction, and sub-surface scattering techniques ensured that there was a real glint to the digital eyes.

“We refracted light using physical attributes and a lens that would mimic real-life physics,” says Culpitt. “It ensured that these characters had a soul.”

Working from the base scans provided by ICT – which offered a mask-like high-resolution version of the actor’s face and skin – Image Engine fleshed out the remainder of the head and neck, cleaning up renders to align them with plate photography captured on set. They also used tools like Yeti to solve the hair, and Solid Angle’s ray-tracing Arnold renderer to achieve a realistic level of skin shading and sub-surface scattering.

However, details needed to be more than skin deep, going beyond pores and eyebrow hairs – Image Engine’s artists needed to look at how these actors moved and reacted, right down to the subtlest flashes of emotion. Artists spent a great deal of time sculpting and adjusting animation to ensure the digi-doubles looked like their real-life counterparts in every scene.

When it came to the challenge of the ‘uncanny valley’ – the gap between humans and their replicas that can create a sense of eeriness – VFX supervisor Jarrett has an interesting response: “He simply said that there isn’t one – the digital doubles either looked like Hugh and Dafne , or they didn’t,” recalls Shawn Walsh, general manager and visual effects executive producer. “That was a massive challenge to our team, but it was also a cool thing to say, because it expressed a belief in us that we’d get there. It grounded us in terms of exactly what the purpose of our work was.”

The old switcheroo

Logan and Laura’s high-end digi doubles were inserted into multiple scenes throughout Logan’s runtime – with the audience none the wiser to the switch.

The Logan digi double was used prominently in an early scene in which Logan and co escape his smelting facility hideaway in a stretch limo. One shot sees Logan captured from side on, wincing as Reaver soldiers ram the vehicle from the left. Although a stunt actor was in the driver’s seat, Image Engine’s Logan head replacement slotted perfectly into the scene, capturing all the exertion and strain acting on the character’s muscles.

Logan’s hero shot – that of the protagonist launching through a pine forest, carving through Reaver soldiers – contained a blend of Hugh Jackman’s performance with that of his stunt actor, with the Logan digi double placed over the top. The end effect, which stitched together four plates, flawlessly disguised the fact another actor was used in-camera whatsoever.

Dafne Keen’s Laura digi-double was also implemented into a number of scenes without revealing anything to the audience. In the smelting facility scene, Laura acrobatically defeats a squad of Reaver soldiers. Again, the scene was performed by a stunt actor attached to a wire. A head replacement transplanted Keen into the scene, with all her apoplectic emotion on show.

Following this, the full Laura digi double was put into action as the character clambers on top of Logan’s limo. Expert lighting ensured the model felt as much a part of the scene as the real actors in camera.

Meticulous matchmoving and tracking ensured that replaced heads were perfectly in sync with the rest of the body. The shots of Keen in action proved particularly challenging due to the wide-ranging expressions she conveyed while attacking her foes – strain, rage, and passion all making brief flashes across her face. Nevertheless, Image Engine’s considered approach ensured the audience never realised the actor had not entered the frame.

“We wanted to keep pushing the realism of these characters as far as we could,” says Culpitt. “You can scan a person and then put in those facial shapes, but if it doesn’t feel like them then it’s not going to work. It takes artistry and an attention to detail beyond the absolute to get something like this to feel right.”

Fighting tooth and claw

Alongside the digi-double shots, Image Engine contributed to a wide array of visual effects necessary to establish the setting and tone of the film.

The team augmented the film’s Eden location with digital matte paintings and CG vehicles, and also added digital corn harvesters alongside plant debris and plumes of FX dust in the Pump House scene. Elsewhere, the team handled blue-screen car comps and complex wire and rig removal.

Image Engine was also responsible for Wolverine’s iconic claws. However, in Logan, there were not two but eight sets of blades to deal with across X-24, Laura and Logan himself. Adding to the challenge was the fact that they were often viewed in the frenzy of violent battles.

“We carried out a meticulous tracking process with the blades, going through frame-by-frame and ensuring everything worked, from the lighting directions to the shadows cast by the blades,” says animation supervisor Jeremy Mesana. “The claws were a cast member all on their own!”

Image Engine’s artists also added shafts of light and glints to the blades, along with arcs of arterial spray, catching and directing viewers’ attention during battle.

A grisly end

The final showdown in the forest between the Reavers and mutant children – the “pinnacle of the movie,” says Culpitt – saw Image Engine develop and deliver various mutant powers. This is seen vividly when one child breathes ice onto an enemy Reaver’s arm, freezing it before shattering the limb.

In another sequence, a flurry of pinecone needles is blasted into an enemy, ripping him apart. Image Engine focused on the speed and movement of the needle attack, ensuring it felt within the realms of physics despite being driven by a telekinetic force.

The Eden forest sequence ends with a brutal showdown between a beleaguered Logan and the savage X-24, culminating with Logan’s impalement against a log.

On-set, Jackman was slammed onto blue mats to provide the basis of the shot, but his body slid against the mat. To get the shot just right, Image Engine stabilized Jackman’s body in the footage, placed his original plate footage head back on, and then reanimated the footage.

This was achieved against a fully CG backdrop, including the log itself. The sequence also saw Image Engine marry footage from both the original shoot and reshoot, which happened in two different locations. With both characters’ faces so close in the frame, it was critical that no detail be spared.

“When you’re working on the death of someone that thousands of people connect with, it’s important to make sure everything feels right,” says Culpitt.

Invisible, yet essential

Image Engine’s work on Logan set a new benchmark for the team in digital double creation, but also for invisible effects in feature film: rarely before has such a complex and demanding CG asset been created, with the intention being for it to remain completely inconspicuous.

“People don’t even know what we’ve delivered on this movie, because they can’t see it,” says Culpitt. “There are sequences where you wouldn’t even know we had touched them, despite having an entirely digital character – you’d think that Jackman had a twin!”

“We just keep getting better and better with the cloth simulations and the way that we deal with muscles, skin and rigging,” he continues. “Continually building on that is the main goal.”

CG supervisor Yuta Shimizu echoes this sentiment, citing Image Engine’s in-house tools, such as Gaffer, in automating and streamlining many processes throughout production: “R&D pushed our tools to enable us to run Logan really efficiently,” he says. “We gained so much from this project that we will most certainly bring into the next one.”

For Walsh, Logan was a huge project; not just in terms of pushing the studio further creatively, but in the level of trust placed in the vendor from a visual effects perspective.

“It’s a big risk to ask for a digital actor of a recognizable person, especially one who is going to stand right next to their real-life counterpart, front and center, but we couldn’t be prouder of the results” says Walsh. “Logan is very much a visual effects film of its time – one replete with the latest in high-end effects, but made naked to the human eye.

“If the audience doesn’t know we were there, then we have certainly done our job.”